Last Sunday, many of our political leaders, feeling pressured by the anniversary of the Armistice that began at the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month exactly one hundred years ago, publicly remembered the generally forgotten dead of the Great War. That war is something any genuine statesman would always keep in mind.

One of the more poignant World War I monuments I’ve seen is in the little Slovak village the Piataks emigrated from well before the Great War. I was a little surprised to see it at all, because the men of the village died defending an empire that ended with the war, one the new government generally viewed with hostility. There are few causes as lost as fighting for something that no longer exists.

I was also surprised by the large number of names on the monument, 18 out of a village population of about 570 at the time. Even before the war there was a shortage of young men in the village: over 400 people had left the village for America. And consider this: most villages in Europe could erect comparable monuments, and most did.

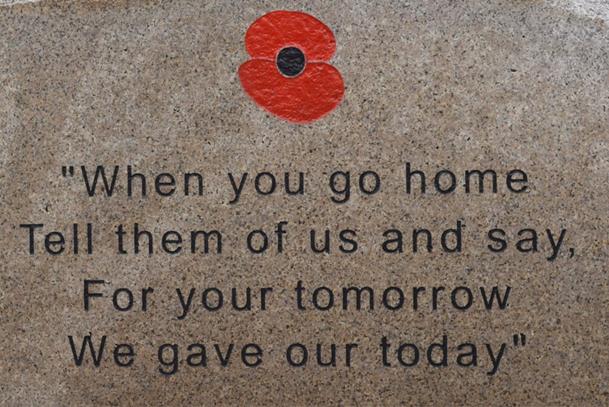

World War I was not as calamitous for all its participants as it was for the Habsburg Empire. But even the victors were worse off for joining that bloodbath, and each participant would have been better off if one of its leaders had taken decisive action to stop the seemingly inexorable march toward war that began with those fateful shots in Sarajevo. Indeed, Western civilization as a whole was grievously wounded by the war Europe’s statesmen failed to prevent, and those wounds may yet prove mortal. Which is why our own statesmen ought to remember that, when it is not necessary to fight, it is necessary not to fight.

Leave a Reply