In his seminal work, Democracy in America, Alexis de Tocqueville noted that the nobility of medieval Europe reckoned martial valor to be the greatest of all the virtues. The feudal aristocracy, he said, “was born of war and for war; it won its power by force of arms and maintained it thereby. So nothing was more important to it than military courage.” In America, it is the “quiet virtues,” argued Tocqueville, that became respected, because they favored the development of trade and industry. Honesty, hard work, and perseverance did more to foster the growth of commerce and the accumulation of wealth than a warlike spirit that could bring glory but disrupt society. “In the United States,” concluded Tocqueville, “martial valor is little esteemed.”

Although Tocqueville had the most perspicacious insight of any foreign observer of the American scene, he got this one wrong. While Americans have embraced the quiet virtues wholeheartedly from colonial times forward, they have also honored martial valor—even demanded it—in their leaders. Perhaps it is better for a commercial society when the people exercise the quiet virtues, but it is reassuring for the people to know that their leaders have demonstrated great courage on the battlefield. It is especially surprising that Tocqueville did not recognize this about Americans since he made his tour of the United States during Andrew Jackson’s presidency. If Tocqueville had lived into the 20th century, he would have seen an aristocracy of warriors develop in the United States. For presidential candidates, military service became almost a requirement.

No one benefited more from Americans’ admiration of martial valor than Andrew Jackson. His parents were Scotch-Irish immigrants from Country Antrim to the Waxhaw settlement on the border of North and South Carolina. His father died before Andrew was born, leaving his mother to rear Andrew and his older brothers, Hugh and Robert. Another brother had been tortured and killed by Indians. Some years later, a neighbor described Jackson’s mother as a “fresh-looking, fair-haired, very conservative, old Irish lady, at dreadful enmity with the Indians.” Mrs. Jackson told her sons that men settle their differences on the field of honor. “Sustain your manhood always,” she counseled. “Never wound the feelings of others. Never brook wanton outrage upon your own feelings.” Andrew Jackson took his mother’s advice to heart.

At 13 years of age, Jackson was already tall and lanky and had great sinewy strength. Even among the Scotch-Irish, whose fury was legendary, Jackson stood out for explosive rages that left him unable to talk and literally frothing at the mouth. “His passions are terrible,” said Thomas Jefferson years later. “When I was President of the Senate, he was Senator, and he could never speak on account of the rashness of his feelings. I have seen him attempt it repeatedly, and as often choke with rage…. [H]e is a dangerous man.” When only a boy, the future dangerous man learned to fight Indians, who were armed and encouraged by the British to attack colonial settlements once the American Revolution erupted. In 1780, his eldest brother, Hugh, just 15 years old, died fighting the British. With their mother’s encouragement, Andrew and Robert joined the local militia and fought in several engagements before they were captured. When a British cavalry officer ordered Andrew to clean his boots, the young rebel refused. The officer immediately drew his saber and swung it at the lad. Andrew partially blocked the blow but was left with a deep gash on his forehead.

Before they were released in a prisoner exchange, the Jackson boys contracted smallpox. Robert died within two days of their release, but Andrew, although he hovered near death for a week, was nursed back to health by his mother. She later died from cholera, contracted while caring for American prisoners of war held in British ships at Charlestown. All of 15 years old, Andrew Jackson was an orphan, a sole survivor, and a veteran of Indian wars and the American Revolution.

In 1788, after studying law and being admitted to the bar, Jackson was appointed the public prosecutor for the “western district of North Carolina,” a region that would shortly become the state of Tennessee. The area was still a wild frontier, and Jackson did more Indian fighting than prosecuting. The Indians were allied with various European powers (the British in particular) and were armed and encouraged by those powers to wreak havoc upon Americans. In Jackson’s first fight against Indians in Tennessee, his militia commander said that Jackson was “bold, dashing, fearless, and mad upon his enemies.”

Jackson’s exploits in battle caused him to rise through the ranks of the Tennessee militia to become its commanding officer and to get elected to the Tennessee constitutional convention, the U.S. House of Representatives, and the U.S. Senate. During the War of 1812, he became a national hero with a series of victories over the British-supported Red Stick Creeks. Jackson was always in the thick of these fights. At Enotachopco Creek, he was described as “Finn and energetic . . . In the midst of a shower of balls, of which he seemed unmindful, he was seen performing the duties of subordinate officers, rallying the alarmed, halting them in flight, forming his columns, and inspiring them by his example.”

As a result of these victories, Jackson was commissioned a major general in the U.S. Army and given command over an area that included Tennessee, Louisiana, and Mississippi Territory. This set the stage for Jackson’s stunning victory in the Battle of New Orleans, where more than 2,000 British were killed or wounded, while only seven Americans were lost. Jackson’s victory humbled the British, saved the West for the United States, and made Jackson an American hero of monumental proportions.

When Jackson later captured Florida for the United States and acted with some disregard for presidential authority, several politicians feared he had Napoleonic designs. From his beginnings as a posthumous child of a Scotch-Irish immigrant father, Jackson had become a warrior aristocrat. That the American people wanted him as their leader was clearly demonstrated when he won both the electoral and popular vote in three presidential races. (The first time, he was robbed of the presidency when, having won only a plurality of the electoral votes, the election was decided by the House of Representatives.) Jackson was the first president not to have come from the planting gentry of Virginia or the New England establishment. To those who followed him, it was clear that one path to the American ruling class was through martial valor. Not surprisingly, nearly all presidents after Jackson served in the military when young, and several were heroes.

William Henry Harrison was one of these. Having dropped out of college to join the Army in 1791, he served in the campaigns against the Indians of the Ohio Valley, distinguishing himself at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794. He left the Army in 1798 with the rank of captain and became the territorial delegate for Ohio and, later, the territorial governor of Indiana. While governor, he took to the field and led a force of regulars and militia against Tecumseh, winning a decisive victory at the Battle of Tippecanoe in 1811 and gaining national acclaim. When the War of 1812 erupted, he was commissioned a brigadier general and given command of the Northwest. He led American forces in recapturing Detroit and then handed the British a shocking defeat at the Battle of the Thames in Canada by ordering an unexpected mounted assault. Leaving the Army as a major general following the war, he was elected by Ohioans first as a representative and then as a senator. In the 1840 presidential campaign, the slogan “Tippecanoe and Tyler too!” helped lead him to a landslide victory.

Zachary Taylor was another war hero. He began his military career in 1808 as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army. Fighting throughout the War of 1812 while serving under Harrison in the Northwest, he was cited for leadership and gallantry and promoted from captain to major. In 1832, now a colonel, he led a regiment in the Blackhawk War, decisively defeating Chief Black Hawk and earning the nickname “Old Rough and Ready.” Three years later, he defeated the Seminoles in the Battle of Okeechobee and was promoted to brigadier general. During the Mexican War, although always outnumbered, he won several battles, culminating in a brilliant victory over Santa Ana at Buena Vista in 1847. Back home, Taylor was hailed as a conquering hero and urged to run for president. Although he was apolitical and had never cast a vote, was a slaveholder running on the Whig ticket, and did not bother to campaign, he won the election of 1848.

A farm boy from Ohio, Ulysses S. Grant graduated from West Point in 1843. Although be had been the best horseman in his class, he failed to get his requested posting to the cavalry and was instead assigned to the infantry. His martial spirit became evident during the Mexican War. Serving with the quartermaster corps at the Battle of Monterrey, he refused to remain in the rear with his regiment’s supplies and instead helped lead the assault. At Chapultepec, he and a small detachment of soldiers dragged a Howitzer to an exposed position and began a bombardment that contributed importantly to the fall of the town. For his gallantry, he was brevetted captain, a rank that became permanent in 1853.

Grant was a warrior, and peacetime service drove him to depression and drinking and to his resignation from the Army. Civilian life was no better. Grant charged back into his natural element when the Civil War erupted, first as the commander of a Galena militia company and then as the colonel of an Illinois infantry regiment. Lincoln soon made him a brigadier general in the regulars. From the outset, Grant was the most aggressive and successful Union general in the western theater. Within two years, he had risen to lieutenant general and earned a reputation for his bold thrusts at the enemy, decisiveness, bulldog determination, and fearlessness. With his transfer to the eastern theater of the war and his eventual victory over Robert E. Lee, Grant became a national hero. Although reluctant to run for president and without political experience, he won easily in 1868 and then, despite mismanagement and scandal in his administration, won by an even greater margin in 1872.

Every president following Grant in the 19th century, with the exception of Grover Cleveland, was not only a Civil War veteran but a hero. Rutherford B. Hayes entered the Civil War as a major in the Ohio militia and ended it as a major general of Volunteers. He was wounded four times and led the final capture of Winchester. Another Ohio boy who rose to major general of Volunteers was James A. Garfield. He distinguished himself in several battles, including Shiloh. Benjamin Harrison, a lawyer from Indiana and the grandson of William Henry Harrison, rose from second lieutenant to brigadier general of Volunteers and brilliantly outmaneuvered Hood at the Battle of Atlanta to force a Confederate retreat. At 18 years old, Ohioan William McKinley enlisted as a private in a regiment commanded by Hayes. McKinley rose quickly to sergeant and then, for gallantry at the Battle of Antietam, was commissioned a second lieutenant. Demonstrating exceptional leadership and valor in fight after fight, he was promoted to major, “If it be my lot to fall,” wrote McKinley in his diary during the war, “I want to fall at my post and have it said that I fell in defense of my country, in honor of the glorious Stars and Stripes.” Nearly 40 years later, he did fall at his post, mortally wounded by an assassin.

When President McKinley died, Theodore Roosevelt took his place. In no other man did the desire to join the aristocracy of warriors burn more fiercely than in Teddy Roosevelt. By birth, he had privilege and social standing, but that was not enough. His own father had remained a civilian during the Civil War, and Roosevelt, though he idolized his father, thought the lack of service was a stain on the family escutcheon. When the Spanish-American War erupted, Roosevelt left his post as assistant secretary of the Navy to organize a unit of volunteer cavalry. Everyone urged him to reconsider his decision, but he would have none of it, saying it was “my chance to cut my little notch on the stick that stands as a measuring rod in every family.” He later wrote, “I want to go because I wouldn’t feel that I had been entirely true to my beliefs and convictions, and to the ideal I had set for myself if I didn’t go” (italics mine).

Roosevelt not only went, but took command of the 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry—the Rough Riders—and led the charge up Kettle Hill during the Battle of San Juan Heights. He was recommended for the Medal of Honor, and the award was endorsed up the line until the secretary of war, for personal and political reasons, squashed it. After a strong lobbying effort, the medal was finally awarded this year, making Teddy Roosevelt and Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., the only father and son who both received the Medal of Honor. The son, a brigadier general, earned his with his death at Omaha Beach.

When the United States was on the verge of entering World War I, Roosevelt offered to raise a volunteer division and to have it privately financed until Congress took action. Applications for the “Roosevelt Division” poured in by the thousands, and the thought of a former American president leading troops at the front electrified demoralized French leaders. “I think I could do this country most good by dying in a reasonably honorable fashion, at the head of my division in the European War,” said Roosevelt. President Woodrow Wilson, however, worried that Roosevelt would not die and would return once again as a hero. Despite pleas from both American and foreign dignitaries, Wilson dared not put Roosevelt in command of anything. Roosevelt fumed and waited stateside while his four sons and a daughter served in Europe: Quentin, a pilot with one German victory to his credit, died in a dogfight; Archie was badly wounded and awarded the Croix de Guerre; Kermit received the British Military Cross; and led, brave to a fault, was both gassed and wounded. Ethel served as a nurse with Ambulance Americane.

Short, bespectacled Harry Truman, a sergeant in the Missouri National Guard, was commissioned a lieutenant when his unit was called to duty in World War I. During the Meuse-Argonne campaign, he was promoted to captain and commanded an artillery battery in some of the hottest action of the war. When the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, Truman was a colonel in the Army reserves and a U.S. senator. Although 57 years old, he requested active duty, but President Franklin Roosevelt wanted the Democrat to remain in the Senate. Also in the Army during World War I but remaining stateside was Dwight Eisenhower. In World War II, he rose to Supreme Allied Commander. When prevailed upon by the Republican party to run for the presidency, he acquiesced and won by a landslide in 1952. Despite a lackluster performance in office, he was reelected by an even greater majority in 1956.

John F. Kennedy’s heroism as skipper of PT 109 (and later of PT 59) in World War II was one of the factors that gave him a narrow victory over Richard Nixon in the 1960 election. The negative whispers about Kennedy did not concern his sexual escapades—the general public was still ignorant of his philandering—but his Roman Catholic faith. “The Pope will rule America, if Kennedy is elected,” intoned his detractors in sotto voce utterances. In addition to other responses, supporters of Kennedy always emphasized his combat in the Pacific and that fateful night in the Solomons when his boat was cut in half by a Japanese destroyer. He was decorated with the Navy and Marine Corps medals and the Purple Heart. This was a man who had fought and nearly died for the flag. Ironically, Nixon also served in the Solomons, but in a rear area. More than once, he volunteered for frontline duty, but the Navy denied his requests.

Another sailor in the Pacific was Gerald Ford, who served aboard the U.S.S. Monterey, a light carrier that saw action in a dozen campaigns. Soaring overhead in a torpedo bomber was a winged sailor, George Bush. His attack on a Japanese radio station, although his plane had been hit and his engine was engulfed in flames, earned him a Distinguished Flying Cross. Another sailor decorated for valor was Lyndon Johnson. A Naval reservist, he was the first member of the House to resign his seat and request active duty. He served only at a desk in rear areas until President Roosevelt, wanting more information about combat in the Pacific, had Johnson assigned to an inspection team. Johnson was aboard a plane near Rabaul when the aircraft suddenly came under fire and had to take evasive action. Somehow, the flight was represented as a daring mission and, although he was simply along for the ride, Johnson was awarded a Silver Star.

Ronald Reagan also served during World War II. He had joined the reserves in 1937 only after a friendly doctor allowed him to fudge an eye exam. When the war erupted, he volunteered for active duty and saw his pay drop from $3,000 per week to $200 per month. After serving as an embarkation officer in San Francisco, he requested a combat assignment but was ordered to the Army Air Corps motion-picture unit at Hal Roach studios. For meritorious performance, he was promoted to captain but refused a promotion to major, saying that he was undeserving of the rank unless he could be sent overseas. The man he defeated in the 1980 election, Jimmy Carter, was a midshipman at Annapolis during the war. He later served on submarines and would have made the Navy a career were it not for his father’s untimely death, which forced him to return home and take charge of the family business.

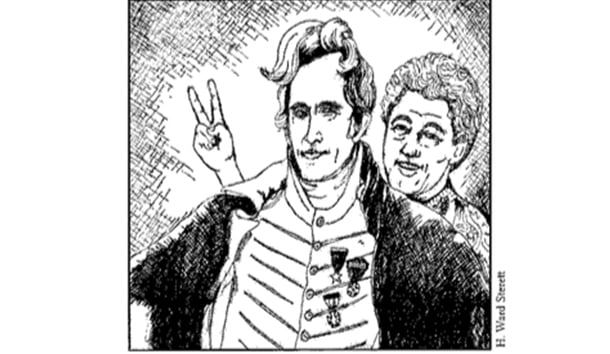

Bill Clinton shattered this record of honorable service. Not only did Clinton not spend a day in uniform, but—facing the possibility of conscription—he proclaimed that he loathed the military. Nonetheless, the desire for a warrior as president persists. Part of the debate over Al Gore and George W. Bush focused on their service records, and the principal reason John McCain surged dramatically early in the race for the Republican nomination is likely the esteem his combat experience as a naval aviator in Vietnam and his subsequent captivity generated. Tocqueville was wrong. Far from being little esteemed in the United States, martial valor is an entree into an aristocracy of warriors and often into the presidency itself.

Leave a Reply