Physicians of the Utmost Fame

Were called at once; but when they came

They answered, as they took their Fees,

“There is no Cure for this Disease.”

—from “Henry King,” by Hilaire Belloc

I’ve spent the last few months hobbling around Manhattan, one of America’s last walkable cities. In keeping with New Yorkers’ well-deserved stereotype for brusqueness, strangers on the sidewalk frequently ask me, “Why are you limping?” My leg and hip pain have increased in lockstep with my rising annoyance at these unwanted interruptions. I never inquire of my fellow New Yorkers’ obesity or depression; why do they pry without hesitation? My doctors have told me my limp will only get worse. I can keep lying to myself and pretend it will magically heal. But eventually the pain will destroy my ambulatory lifestyle. Walking just a few blocks will soon become impossible. And the discomfort will also steal my sleep. I have been putting off double hip replacement surgery out of both fear and busyness. Chronic pain has darkened my brightest days. But my pain inexplicably disappeared on December 29 when I received a diagnosis of Stage 4 oropharynx cancer.

Now my lower-body pain doesn’t even register. My hips and knees hurt when I walk? Too bad. Or maybe I should say, “Who cares?” In the last few weeks I have looked back nostalgically on the days when scaling a subway staircase posed the biggest challenge in my life. Thanks to cancer—the modern-day plague—I will soon undergo surgery followed by seven brutal weeks of radiation and chemotherapy. And if all goes as my doctors hope, my odds of survival stand at a whopping 50 percent. After learning of my coin-flip existence, one quick-thinking friend tried to cheer me up by reminding me of Jim Carrey’s character in the 1994 comedy Dumb and Dumber, who enthusiastically exclaimed upon hearing his one-in-a-million odds of getting the woman of his dreams, “So you’re tellin’ me there’s a chance? Yeaaaahhhh!” By my math I should be 20,000 times as excited. Yeah!

My diagnosis has rejuvenated me. It has made me excited to give thanks for all the positive aspects of my life, which until December 29 barely registered. Immediately after I told a few friends, my texts and email account jammed with hurried communications from the concerned. I heard from grammar-school friends I hadn’t spoken to in 40 years, high-school friends and teammates I hadn’t spoken to in 35 years, college friends, teammates, and coaches I hadn’t spoken to in 30 years. My dissertation committee reached out. Business, professional, and social contacts called, wrote, and stopped by. Old friends with whom I had long ago fallen out rang to say all was forgiven. And my friends offered help and assistance—and promises of more to come after my treatments start—along with their good wishes. I am blessed to have run across such a humane crowd in my 53 years on earth. I don’t deserve them, and they don’t deserve this.

And I can’t even begin to explain the bountiful good luck I have had since December 29. How lucky am I to be undergoing this procedure in the United States, as opposed to, say, Haiti or Uzbekistan? How lucky am I to be fighting cancer in 2018 instead of 1918, when I might have been whisked off to an institution to wait out my prolonged and painful death? In Let Me Down Easy, Anna Deavere Smith likened cancer treatments to “beating the dog with a stick to get rid of his fleas.” But my oncologist told me my cancer drug won’t make me lose what little hair I have left. How lucky am I that one of the world’s top head and neck surgeons decided to accept me as a patient the week between Christmas and New Year’s, instead of fleeing New York for warmer climes the way every other member of his socioeconomic caste does? How lucky am I that several of the world’s top cancer hospitals lie within a 1.5-mile radius of my apartment? Luckiest of all, with my wife leading the charge I have the smartest, most dedicated, and most compassionate partner with whom to battle this deadly malady. If cancer were Powerball, then I just won it, three drawings in a row.

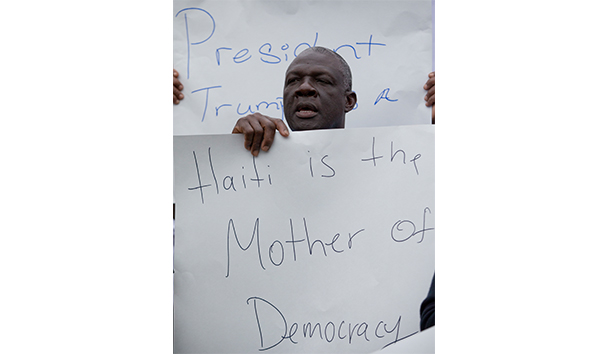

This morning I woke up, newly thankful for my good fortune, to the global howls arising from Donald Trump’s latest misstep, “Shithole-gate.” After wiping the smirk off my face, I paused to take in the vitriol spewed by the offended. Do the likes of MSNBC’s Joe Scarborough and CNN’s Don Lemon ever ask themselves why Haitians want to flee their country in the first place? How many off-site meetings has the New York Times editorial board held in Port-au-Prince? Why has Haiti been the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere for decades now? Haiti’s murder rate topped out at 219 per 100,000 in 2004 during President Aristide’s reign; in comparison, Norway’s murder rate in 2014 registered 0.56 per 100,000. The IMF reported a 2016 per capita GDP of $70,392 for Norway compared with $761 for Haiti. Where would you rather live?

On December 29 I moved to a shithole myself. It’s called Cancer World. The life expectancy in my country falls far below that of the OECD countries, we have zero tourism, and depression ranks as the national mood. We involuntary subjects live under the rule of an invisible tyrant, who allows emigration from Cancer World only to those who accede to—and survive—his diabolical chemical and radiological experiments. Most citizens while away their days wavering between resignation and anger. Our natural landscape contains an endless vista of tombstones. All the undeveloped land has been reserved for yet more graves. We don’t care about global warming or the intersectionality of racism or income inequality or anything else those hypocrites with decades-long time horizons worry about while they’re driving their air-conditioned SUVs, paying private-school tuitions to avoid those of a darker hue, or demanding upgrades to business class based on their frequent-flyer status. Puddles of vomit dot the sidewalks, and the food has no flavor. There aren’t many children resident in Cancer World, but that’s fine. While their laughter and energy would brighten our bleak existence, we fear our holocaust-victim appearances would scare them, even though they look just like us. We would welcome President Trump denigrating our homeland as a shithole; such an ill-mannered yet spot-on remark would highlight our plight. And, more deliciously, it would drive Anderson Cooper to tears yet again. Stop crying, Mr. Gloria Vanderbilt, Jr. Do something, and not something driven purely by ratings.

I can’t honestly say whether I’d rather move to Haiti or stay trapped here in Cancer World. But instead of spitting up their lattes and tweeting their outrage because President Malaprop just blurted out something too close to the truth in regard to less fortunate parts of the world, maybe it’s time for Americans to give thanks for all the blessings and good luck they enjoy. We waste the third Thursday of every November overeating, watching the Detroit Lions lose, and mumbling a few platitudes about thankfulness before passing out on the living room couch. I won’t say I’m thankful I got cancer and now reside in a shithole. But I’m thankful I got it here and now, and all while surrounded by wonderful friends from every period of my life.

Leave a Reply