We often measure the significance of a particular cultural work by establishing whether it’s withstood the test of time. It’s not a bad way of assessing the universal and perennial nature of things. Bing Crosby is not only part of the American cinematic pantheon but also a permanent part of American culture. His work has withstood the test of time, and this is especially obvious during the holiday season. Whether it’s Holiday Inn (1942) or White Christmas (1954), Crosby’s work always brought a sense of joy and humor along with his singing talent. Although both films have a specific plot, they both are “Bing Crosby pictures.” He is at the center of both films as Fred Astaire and Danny Kaye bring comic relief in their supporting roles.

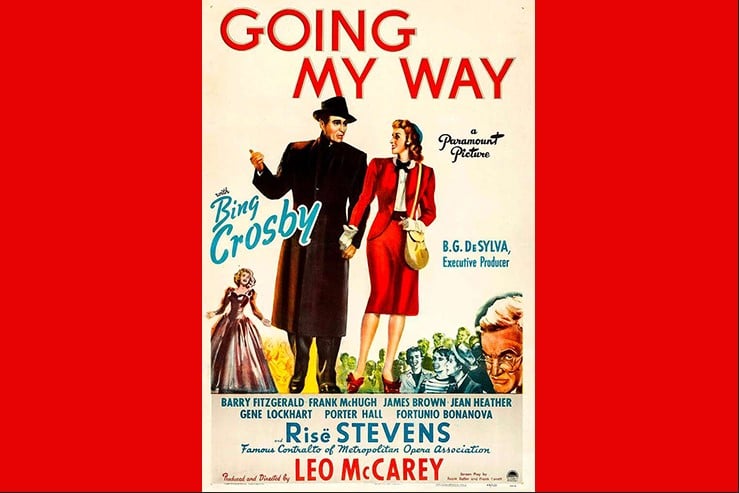

In Going My Way (1944), music is still very much an important element of the film, but Crosby is not at the center. Rather, the life of an old priest is what gives the film its meaning. Crosby plays Fr. Chuck O’Malley, a young priest who is transferred to St. Dominic’s—a New York Irish parish. St. Dominic’s is on the verge of foreclosure and Fr. O’Malley is supposed to take charge of the parish. There is one little caveat: Fr. Fitzgibbon (played wonderfully by Barry Fitzgerald) was not supposed to find out that Fr. O’Malley is in charge.

The two priests start off on the wrong foot. Through a series of unfortunate (but not serious) events, Fr. O’Malley first appears to Fr. Fitzgibbon in a sweat suit bearing the name of his alma mater. This doesn’t impress the old priest. O’Malley’s forward-thinking (described in the film as “progressive) nature, love of golf, and incessant singing is certainly not “helpful” to Fitzgibbon’s way of thinking.

O’Malley is hardly progressive in our sense of the word. He is recognizably a priest strictly, but goes his own way in clothing and personality. He often eschews his cassock for baseball jackets and hats. In addition, religion doesn’t have to be a “dirge,” says O’Malley but he also understands that fun and humor cannot its driving force. Fundamental understanding of theological principles must remain the foundation.

Like any old person, Fitzgibbon is set in his ways. One really can’t blame him; after all, he built the parish and has been its pastor for almost 46 years. He has sacrificed everything for it, so much so that ever since he left “the old country” (Ireland), he has not seen his dear mother. Since that departure from Ireland and his mother, time has marched on and the culture around him has been changing, as it tends to do, and this is where O’Malley comes in.

Whether it’s his youth or an easy-going personality, O’Malley is able to get through to a lot of obstinate people who are contributing to the decay of the parish. In order to get the kids in the neighborhood off the streets, he forms a boys’ choir (in real life, this was the Robert Mitchell Boys Choir), and the boys’ behavior (which unfortunately included stealing) begins to change.

O’Malley’s good influence and positive attitude do not, by themselves, translate into raising money for the parish, however. So the matter of the parish mortgage remains a worry. Quite by chance, O’Malley visits his longtime friend, Jenny Tuffel who is now an opera star called Genevieve Linden (played by the real-life Metropolitan Opera mezzo-soprano, Risë Stevens). It’s clear that Jenny was at some point a love interest. She wonders why her good friend Chuck stopped writing to her. It’s only after O’Malley takes off his winter coat that she sees his priest’s collar and realizes the reason for his exit.

Jenny decides to help the parish by recording a song—”Going My Way”—and to sell it to help raise enough money to avoid foreclosure. But the song turns out to be too “high minded” for the record company. In the end, the unlikely song that saves the church is “Swinging on a Star,” a popular tune written especially for the film.

Nothing prepares O’Malley or Fitzgibbon for what comes next. The church is damaged by a devastating fire, and Fitzgibbon knows that he must sacrifice himself to begin building it all over again. Instead of sailing back to Ireland to see his mother one last time before she dies, he decides once again, not to abandon his flock. O’Malley, however, arranges a surprise for him, a Christmas miracle if you will.

Going My Way is subtle in its delivery of morality. It never preaches at the audience. To be moral is to be joyful in a theological sense. Naturally, the film keeps close to Catholic doctrine, but it is about so much more than being Catholic—it’s also about being Irish but especially about being American.

In fact, one could consider Going My Way radical in its presentation of American Christianity. While most films were comfortable in showing some version of White Anglo-Saxon Protestantism, a mere allusion to Christianity, Leo McCarey’s direction and story offer a vividexperience of being Irish in New York. The beauty and grittiness of New York’s strange melting pot (in this case, including the Italians and the Irish) is a source of cultural comfort and stability, set in its time and place. What did itmean to be a Catholic in America at that time, and no less, someone planted in both the “old country” and “the new world?”

These questions should induce no negative sentiment. The questioning need not one of mere politics. In fact, it is supremely spiritual. Bing Crosby brings here not only “the luck o’ the Irish” but of the American too. In our time, much of this appears as a lost world. Even so, we should remember as Fr. Fitzgibbon had to learn, that while the landscape always changes, the fundamentals still exist—as does the spirit of Christmas, be it in an Irish lullaby or Schubert’s Ave Maria.

Leave a Reply