A station agent tried to telegraph Price, Utah—the direction the outlaws were headed—but Butch Cassidy and Elzy Lay had cut the wires. The paymaster had the train’s engine uncoupled. Men grabbed a variety of weapons and jumped aboard. The locomotive steamed down the narrow gorge of Price Canyon right past the unseen robbers, who were changing horses behind a section house. Cassidy and Lay escaped by a circuitous route, eventually doubling back and reaching Brown’s Hole some $8,000 richer. Posses from Castle Gate and nearby Huntington became so confused that they wound up shooting at each other.

The robberies at Montpelier and Castle Gate demonstrated that Butch Cassidy had brought to perfection techniques that he had learned while riding with Tom McCarty. Butch was taught how to ride, rope, shoot, and steal horses by Mike Cassidy, and then how to rob banks—and, equally important, how to escape—by Tom McCarty.

Cassidy stationed relays of horses along a planned escape route. Several weeks before a robbery he would train the horses to be used in the getaway. Well-bred animals were selected, grain fed, and exercised rigorously. For the robbery sure-footed, stocky horses of great short-distance speed were selected. When the first relay was reached, Cassidy switched to taller, leaner thoroughbreds able to maintain a swift pace over a long distance. If necessary, a second, and even a third, relay of horses was used. Relays of fast, well-conditioned horses and well-planned escape routes became Cassidy’s trademark.

About a year after the Castle Gate payroll robbery, a posse descended upon some outlaws in Robbers’ Roost, a hideout in southeastern Utah. In an ensuing gun battle two of the outlaws were killed. When the posse with the two dead outlaws arrived in Price, Utah, the bodies were identified as Butch Cassidy and Joe Walker.

Butch heard about it and hurried to Price to attend his own funeral. Hiding in a wagon, he was touched by the emotion displayed at his passing, especially all the crying women. He later told his family that it was a good idea to attend his own funeral just once during his lifetime. “No, it sure wasn’t me,” Butch added. “He was better looking.” The body was later correctly identified as Johnny Herring, a young cowboy who bore a striking resemblance to Cassidy.

Douglas Preston, an attorney in Rock Springs, Wyoming, was Butch Cassidy’s lawyer. Whenever any of the Wild Bunch got in trouble, it was Preston who defended them, usually with success. Preston would later become a state legislator and then the attorney general of Wyoming. Preston said that during a saloon brawl, Cassidy had saved his life, and, in gratitude, he promised to defend Butch whenever the need arose.

Butch and his gang pulled their first train robbery at Wilcox, Wyoming, in June 1899. They put a red lantern on the tracks of the Union Pacific Overland Flyer just before a wooden trestle. The train screeched to a halt, the engineer fearing the bridge was out. Two of the gang, Harvey Logan and Elzy Lay, leaped into the cab of the locomotive, beat the uncooperative engineer, and drove the train across the bridge. Behind them a dynamite charge exploded, and the bridge was blown to pieces.

Cassidy and the boys then surrounded the express car and shouted to the messenger inside to open the door. “Come in and get me,” replied Ernest Woodcock. Cassidy answered by lobbing a lighted stick of dynamite under the car. The resulting blast blew out one side. Woodcock was thrown the entire length of the car and knocked groggy, but otherwise unhurt. Harvey Logan put a revolver to Woodcock’s head and cocked the gun. “Let him alone, Kid,” Butch yelled. “A man with his nerve deserves not to be shot.”

The gang then blew the safe apart with still more dynamite, too much in fact. Bonds and money were blown all over the area, and the outlaws had to scurry about to gather some $30,000 in loot.

A few hours later a special train was dispatched to the scene from Cheyenne, 120 miles away. The train carried railroad detectives, Pinkerton detectives, and a posse with horses. Another train, with several flatcars carrying men and horses, was dispatched from Laramie. The lawmen rendezvoused at Wilcox and then set out upon the trail of the Wild Bunch.

At one point a posse from Converse County had George Curry, Elzy Lay, and Harvey Logan cornered, but after an all-day gun battle the outlaws managed to escape and eventually rejoined Butch. The robbers were using new rifles and smokeless powder, which gave them a distinct advantage over the county posse.

After the initial chase, the Union Pacific hired the Pinkertons for long-term tracking. The Pinkertons put two of their best operatives, Charles Siringo and W.O. Sayles, on the assignment.

By 1900 Butch Cassidy was 34 years old. For the past four years he had been hunted intensely by lawmen throughout the West. One by one the refuges for the Wild Bunch—Robber’s Roost, Brown’s Hole, and the Hole-in-the-Wall—had been penetrated. Settlement of the frontier, with accompanying railroad networks and advancements in the telephone and telegraph, all but cut off former escape routes. The American frontier in which the horseback outlaw had thrived was nearly gone. Several members of the gang had been killed or captured.

As a consequence, Cassidy met privately with Judge O.W. Powers in Salt Lake City. Cassidy requested that Powers ask Utah governor Heber Wells for amnesty in exchange for Butch’s promise to go straight. Cassidy’s earnestness won over Powers. Governor Wells was impressed by Cassidy’s plea, but said that there was no legal precedent for such a move. He could not pardon Butch for crimes committed in another state, especially crimes for which the outlaw had not yet been tried.

Governor Wells suggested an alternative. If Cassidy would request the Union Pacific to drop charges in exchange for a promise that his robberies would cease, Wells would use his influence in helping Butch get a fresh start. It was further agreed that Cassidy would volunteer his services as a railroad express guard, believing that the railroad would see the advantage of having the notorious outlaw working for them.

Together with his lawyer, Douglas Preston, and aided by Governor Wells’s influence, Cassidy arranged to meet with Union Pacific representatives to negotiate a truce. To avoid any chance of treachery he asked that Preston bring the railroad officials to the Lost Soldier stage station at the base of Green Mountain in Wyoming.

The railroad contingent was delayed en route, and when the hour of the rendezvous came and passed without Preston and the Union Pacific representatives showing up, Cassidy gave up, leaving behind an angry note: “Damn you, Preston, you double-crossed me. I waited all day but you didn’t show up. Tell the U.P. to go to hell. And you can go with them.”

Responding to what Butch believed to be the Union Pacific’s treachery, he decided to strike against the railroad as soon as possible. Late in August 1900 a Union Pacific train passed the station at Tipton, Wyoming, and began the climb uphill toward Table Rock. Butch Cassidy and the boys went into action.

They swung onto the coal tender and then climbed into the cab of the locomotive. Logan stuck a revolver into the engineer’s ribs and ordered him to stop the train. Ed Kerrigan, the conductor, came running forward to investigate. When told to uncouple the passenger cars, he refused, saying he had to set the brakes first or the cars would roll back down the grade and the passengers would be killed. The outlaws allowed him to set the brakes and then, with the cars uncoupled, had the engineer steam a mile or two ahead.

Butch found the messenger inside the express car was none other than Ernest Woodcock. Again the brave messenger refused to open the door. Looking at the Wild Bunch’s dynamite, Kerrigan convinced Woodcock to comply this time. The outlaws then blew the safe and got away with $55,000.

The Union Pacific was prepared for a chase. Timothy T. Kelliher of the railroad had organized the Union Pacific Mounted Rangers specifically to track the Wild Bunch. The U.P. Rangers had a special train outfitted with a loading ramp for horses, stalls and hay, a dining car, a fast locomotive, and a veteran engineer. The Rangers were equipped with the best horses money could buy, high-powered Winchesters, and powerful binoculars.

When Butch learned of the special train and the Rangers, he reckoned his days of robbing trains were at an end and decided he should try his luck in South America. Before he left, though, he wanted a bit more cash. In September 1900, he, Harry Longabaugh, and Will Carver walked into the First National Bank at Winnemucca, Nevada, and left with more than $30,000.

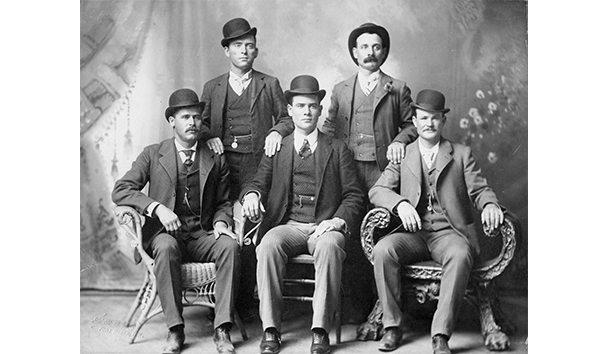

After eluding pursuing posses, Cassidy, Longabaugh, and Carver headed for Fort Worth, Texas, to live it up in “Hell’s Half Acre,” the red-light district. There they met Harvey Logan and Ben Kilpatrick. Flush with money, they bought expensive clothes, including tailored suits and derby hats, and posed for a group photograph.

Fred Dodge, a Wells Fargo detective masquerading as a gambler, happened to stroll into the photographer’s gallery where the group picture was on display. Dodge recognized Carver. Taking the photograph to headquarters, he was able to identify the others, and the hunt was on. Meanwhile, the Wild Bunch headed for San Antonio and Fanny Porter’s brothel.

At Fanny Porter’s Harvey Logan fell for Lillie, one of the prostitutes, and Will Carver picked up Laura Bullion. Butch bought a bicycle—bicycles were the new fad in the West in 1900—and entertained everyone at Fanny Porter’s by riding up and down the street and performing tricks on the bike.

In February 1901, Harry Longabaugh, Etta Place, and Butch Cassidy were in New York City. From there they sailed to Argentina, eventually followed by Pinkerton detective Frank Dimaio. They received a land grant near Cholila in the province of Chubut and stocked the land with horses and cattle. They worked their ranch quietly and successfully until 1906.

Then, with Etta Place, they began robbing banks. They took $10,000 from the National Bank in Central Argentina and $20,000 from a bank in Río Gallegos. Mrs. Bishop, the wife of the bank president in Río Gallegos, said that the robbers posed as cattle dealers and that the girl was very sweet and attractive. Mrs. Bishop also said that before the robbery she had been admiring the girl’s riding clothes and English saddle. Soon they were known as the Bandidos Yanquis.

In 1907 Etta Place returned to the United States for medical treatment. Butch and Sundance went to work for the Concordia Tin Mines near La Paz, Bolivia. Butch used the name Santiago Maxwell, and Sundance called himself Enrique Brown. They stayed there until 1908.

In 1908 Butch and the Sundance Kid staged their last holdup when they intercepted a mule train with the payroll for the Aramayo mines. Butch made the mistake of taking not only the gold but also a big, silver-gray mule. Sometime later, Butch and Sundance rode into the village of San Vicente, where a hotel owner, who was also the local corregidor, recognized the mule. While his wife prepared a meal for Butch and Sundance, the corregidor rode to contact a troop of Bolivian cavalry nearby.

As Butch and Sundance were eating on the hotel’s patio, the soldiers rode up, and the captain called for the Bandidos Yanquis to surrender. Those were his last words. Sundance fired and blew him out of the saddle. Another soldier raised his rifle, and Butch shot him. The shooting became general. Butch and Sundance had put their Winchesters and extra ammunition across the patio, and Sundance made a dash to retrieve them. On his return he was hit by several rounds and dropped to the ground. Butch dragged him back to cover, and the two continued fighting until Sundance died and Butch had only one round left. Badly wounded, he used his last bullet to shoot himself. He was 42.

“Butch Cassidy, Part 1” appeared in this space in the October issue.

Leave a Reply