For decades, stories about the struggles of cancer patients have been a recurrent theme in American cinema. It’s worth reflecting on what drives this, the things such movies have in common, and what they may tell us about the human condition. Patients presented in these movies are typically shown to be dying as a result of their incurable illness. Looking at a few examples of such heart-rending productions may throw light on how those who produce and act in such movies are trying to reach their audiences emotionally. That these movies have often done well at the box office is noteworthy, since their subject is far from pleasant. Indeed, one might wonder why any movie watcher would consider them to be entertainment.

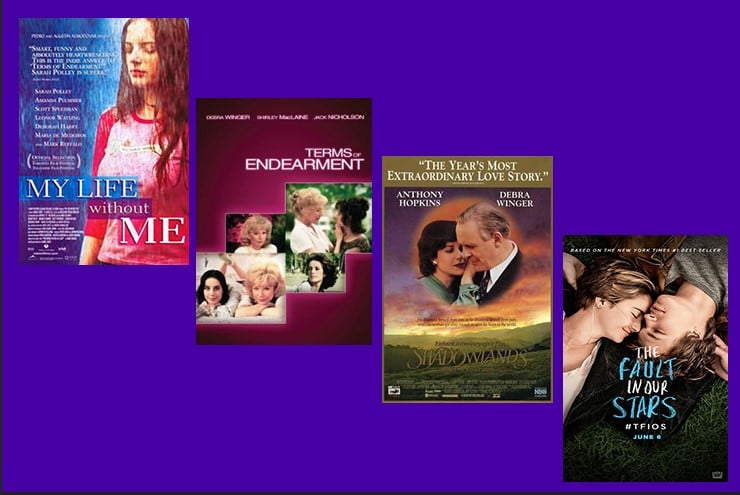

The 2003 Canadian film, My Life Without Me, presents a seemingly healthy, hard-working young mother of two, Ann (Sarah Polley), who learns she has advanced ovarian cancer. Ann makes the decision to withhold this information from her devoted husband, Don (Scott Speedman) and the rest of her family and sets about making plans for their future without her. In between tender moments with her family, a controversial affair with another man (Mark Ruffalo), and Ann’s reconciliation with her parents, she records tapes for Don and the girls so they can keep her in their thoughts when she’s no longer there to care for them. It’s a truly heartbreaking movie.

My Life Without Me is one of many films from the past five decades that deals with cancer and its ravaging effects on both its victims and their families. Ovarian or breast cancer are often the main sources of grief in these women-centered films. Take, for example, the 2001 film Wit, in which Emma Thompson plays Vivian, a professor whose work explores religion and death. Vivian must contend with her own mortality when she learns she has ovarian cancer. The film also shows how devastating experimental treatments can be. Even famed film critic Roger Ebert, who died of cancer, cited the movie as being “too graphic to watch” as it brought back “many vivid and painful memories of treatment.”

Perhaps the most iconic film capturing the grueling and unrelenting heartache of cancer loss is Terms of Endearment (1983) in which Debra Winger, a young, seemingly healthy mother, receives a terminal breast cancer diagnosis and her precarious relationship with her estranged mother, played by Shirley MacLaine, is put to the test. The film was considered a comedy-drama in the 1980s, and the interwoven humor was the antidote to the weighty gravitas of the big “C.” Nowadays, such a depiction would be verboten.

Hollywood films centered on cancer nearly always feature someone slowly dying and then dwell on the loss suffered by those left behind. Take for example Shadowlands (1993) starring Anthony Hopkins as C. S. Lewis, famed novelist, theologian, and author of A Grief Observed. The film is a dramatized account of Lewis’s loss of his wife, poet Joy Davidman (Debra Winger), who succumbed to metastasized breast cancer. The movie depicts Lewis’s anguish as he begins to lose her to the ravishes of the illness. Theirs was a short-lived relationship, unfortunately.

Each of these films elicits empathy for the cancer victims and their families while simultaneously making us aware of how good it is to be alive and healthy. The underlying message: If lower back pain is the worst affliction you have, then don’t complain. Overall, these films increase awareness of cancer and occasionally make health information accessible to the public. But there’s evidence that watching such films might sometimes perpetuate misinformation.

A study published in January 2024 by JCO Oncology Practice and supervised by oncologist David J. Benjamin indicates that Hollywood films may provide unrealistic depictions of cancer and create false impressions about available treatments. The study notes the disproportionately grim outcomes of the cancer cases in films as compared to real life.

In recent cancer-centered movies, brain cancer has a lead role, but in point of fact, that cancer is not even in the top 10 types of cancers diagnosed in the U.S. In contrast, lung cancer, which is the second most common cancer in the U.S. gets barely a blip on the screen. The prevalence of brain cancer in cinema might also have to do with the fact that this illness has skewed toward younger people in the past 25 years. In 2021, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, brain cancer was the most common type of cancer killing youth.

Popular cancer films appealing to younger audiences feature attractive young people fighting terminal illness while also embarking on intense romances (e.g. A Walk to Remember, 2002). This theme reappears in the high-grossing adaptation of John Green’s young-adult novel, The Fault in Our Stars (2014) in which a 16-year-old cancer patient, played by Shailene Woodley, attends a support group, where she meets and falls in love with another cancer patient, played by Ansel Elgort. This film was cited in a TIME Magazine article, entitled, “The Difference Between Cancersploitation and Art—According to a Cancer Survivor.” The writer of that piece asks an interesting question about whether filmmakers take their subject seriously as a human tragedy or merely regard such cinematic work as “cancersploitation” and a cheap way to turn out young audiences.

It may be difficult to answer this question definitively, but there is something undoubtedly worthwhile about such films. Cancer films may not bring fully to light the financial burdens and state-of-the-art treatment for cancer. But they do depict the workings of the human mind when faced with mortality. The stories, moreover, are engrossing enough to attract many viewers, who may be looking for something more than entertainment in films.

Leave a Reply