Sometime in the early 1980’s, terrorism ceased to be seen as a tactic and became a movement. Originally, the term referred to acts committed by a government against its own people, on the precedent of the French revolutionary Terror in the 1790’s. Gradually, the word shifted its meaning, to denote violent resistance against governments; and most recently, Terrorism (usually capitalized) became the specter haunting the West, the armed fist of Islamic and Oriental despotism against democracy and Judeo-Christian civilization. This monstrous empire had its distinctive geography, with seats of peculiar evil in Damascus and Tehran, Khartoum and Tripoli. Terrorism thus construed was a force Out There that threatened our cities and streets: the nightmare was that it could someday “come to America.”

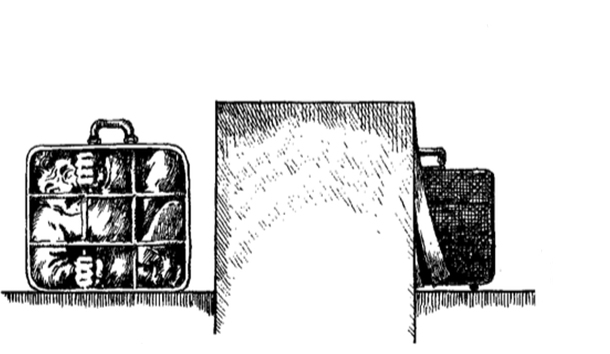

While this vision was always flawed, the whole concept of terrorism as an alien and Oriental force seems particularly tenuous after the Oklahoma City bombing, which led many writers to recall the lengthy history of violence within the United States. However, the idea of terrorism as a Middle Eastern predilection still pervades Western attitudes, both at the popular and political levels. It is most in evidence following some terrorist spectacular like last year’s attack on American forces in Saudi Arabia or (arguably) the downing of TWA Flight 800. At these times, the media are generally full of elaborate flow charts depicting the dissemination of money and techniques from particular countries to international groups and individuals, whose networks are drawn with loving care. This material permits governments to declare that action X can infallibly be associated with Group Y, which serves as a surrogate for nation Z; which in the correct circumstances can thus qualify itself to become the target of American bombs or Cruise missiles.

Remarkably, virtually nobody ever questions the attributions of blame offered in such accounts, whether they derive from the elite journalists of the New York Times and Wall Street Journal or from the talking heads on the Cable News Network, Ted Turner’s very own News Lite. Do these people really know what they are talking about? And even if they did, would they be presenting the unvarnished truth to the watching millions? This lack of critical assessment is striking because we now know enough to say that for over a decade, a sizable proportion of the interpretations of terrorism emanating from these same sources was bunk. Real perpetrators of terrorism were by and large ignored, usually because they were seen, however improbably, as our friends, while other petty villains were constantly highlighted and exaggerated because they had offended the wrong people and often lacked the military strength to prevent them from being penalized (frequently for the crimes of others). Moreover, these misinterpretations were well known to policymakers at the time. It may be, of course, that these problems are now wholly resolved, and that governments and intelligence agencies are telling the media the whole pristine truth about what they know concerning terrorist actions, but this seems improbable.

Political distortions affect not only the grand picture of terrorism, but also the investigation of terrorist acts. Contrary to the rhetoric of impartial science and forensic investigation, such reconstructions tend to be a profoundly political process, in which blame is attributed through a kind of intuition, subject to political pressure. Results are arrived at through negotiation, and evidence is then highlighted or discarded to achieve and publicize a desired result. The resulting interpretation then enters the realm of universally acknowledged fact, and in turn shapes future investigations: if I had not believed it, I would not have seen it with my own eyes!

The difficulties inherent in understanding terrorism can be illustrated from the terrorist wave that appeared to sweep over Western countries in the mid-1980’s, and specifically during the one year of 1986. This was the time of such atrocities as the Istanbul synagogue massacre, the devastating series of bombings in Paris, and attempts to blow up Israeli and other Western airliners. That April, President Reagan decided to take a leaf out of the Israeli book, and sent aircraft against Libyan targets: he thus followed the “stand tough” strategy advocated by up-and-coming Israeli diplomat Benjamin Netanyahu. Though the Libyans were the most conspicuous international villains, Western politicians and media also sustained intense propaganda campaigns against other perceived bandit states, including Syria and Iran.

A case can be made for dismissing “international thugs” like Syria, Libya, and Iran as deeply corrupt and violent despotisms, and there is no question that at some point each government did indeed indulge in terrorist activity. However, in each of the cases in which they were most directly blamed for sponsoring terrorism, we now know that they were, if not innocent, then at least not guilty of the specific charges leveled against them. Moreover, Western governments knew this at the time. When, for instance, Reagan ordered the bombing of Libya, this was in response to the reported interception of messages which clearly implicated Libya and Syria in an attack on American servicemen. And Syria? So why exactly were the bombs not falling on Damascus? One perennial answer is that Libya is a convenient country to bomb: it has weak air defenses, a paltry military, and virtually no friends and sympathizers. In every way, it is the mirror image of well-armed and well-connected Syria. The question for international law, order, and justice thus proceeds on the familiar law-enforcement maxim of “leave the powerful guy alone, and arrest the street thugs.”

At other times, however, the Syrians did become the prime suspects, a role greatly enhanced by the visceral enmity between that nation and Israel. One still-baffling case involves the 1986 attempt by a Jordanian man to blow up an El Al airliner by persuading his unsuspecting pregnant girlfriend to travel on the plane with a suitcase full of explosives. The plot was detected, the airliner saved, and international sanctions descended upon the Syrians. It was all very black and white, until a journalist some weeks later succeeded in eavesdropping on a conversation between the German Chancellor and French Prime Minister, who were chortling over the brilliance of Israeli intelligence in setting up such a bogus plot, which had produced such wonderful diplomatic results. The taped conversation might have been mere gossip, but one would think that two such powerful leaders would have very good access to intelligence sources of their own.

The overarching interpretation of blame sometimes affects both the direct investigation of the act and its treatment in the media. Consider, for example, the heinous attack on an Istanbul synagogue in 1986, in which 21 worshipers were killed, along with two terrorists. The New York Times published a model investigation of this crime by correspondent Judith Miller, who has since emerged as an influential expert on Middle Eastern terrorism (see, for example, her recent book God Has Ninety-Nine Names). Despite the author’s credentials, the Times story is a fascinating example of the selective and ultimately misleading presentation of evidence.

The specifics of the incident are crucial to establishing a political context. According to Miller, two terrorists carried out the attack prior to locking the synagogue doors and committing suicide with grenades, a violent exit they had planned from the beginning. This tactic is highly informative for attributing blame for the act, as it virtual proves that the culprits must have been Muslims of fundamentalist disposition, probably connected with a Shiite group (Christian terrorists, Arab or Armenian, are far less likely to engage in suicide attacks). This leads Miller to a trail of evidence that indicts the usual three suspects for sponsoring the act: Libya, Iran, and Syria, working through the notorious “Abu Nidal” group. The problem in all this is that we have other accounts of the deed, which are quite different from the Times story. According to Turkish police reports, several men entered the synagogue, and some ran off when the police arrived. Two others blockaded themselves in the building, and probably blew themselves up by mistake.

The difference in the stories may seem trivial, but it radically changes our ideas of the groups likely to have been responsible. It also illustrates the fact that reports of terrorist incidents are often conditioned by self-interest. The Turkish police did not want to admit having lost major terrorists, and were anxious to portray the violence as having come from outside their own country. Moreover, Turkey desperately needed to establish its credentials as a worthy partner in the European Community, and being a “victim” of Arab terrorists would have certainly helped its case. Better still, the Israeli sources (on which most terrorism reports rely) were quite delighted to fuel the ongoing effort to discredit the Damascus regime.

To think of a recent American parallel to such political considerations, think of the furious debate over the investigation of TWA Flight 800, in which the airline, the engine-makers, and the victims’ families all had massive financial and political stakes in the question of whether the incident resulted from a bomb, a missile, or a mechanical disaster, and how each group has tried to emphasize evidence beneficial to its own perspective. But perhaps the most notorious example of a self-interested investigation concerned the horrifying bomb attack in 1988, which brought down Pan Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland. Anyone wishing to observe Orwellian principles at work can do no better than to trace the attribution of blame for this crime, which within a few months had been unequivocally laid at the door of two nations, Iran and (who else?) Syria. From mid-1989 through mid-1990, we knew precisely which Palestinian group had done this, and for what motive (revenge for the accidental downing of an Iranian airliner by an American warship). Books, documentaries, and television movies all presented the same account, naming names and even depicting in fictionalized form the scene in which an Iranian minister gave a terrorist leader the multimillion-dollar payment for carrying out the deed. The whole framework was as clearly part of the historical record as the events of the Battle of Gettysburg: the only difference is that the Pan Am 103 story has since been changed, with the leading characters thoroughly altered. Today, not only are Syrians and Iranians not blamed for this crime but it appears from some texts that they never were serious suspects.

The reason for this universal volte face can succinctly be described as Saddam Hussein, whose invasion of Kuwait in August 1990 set off a huge international crisis, following which George Bush cobbled together a large but fragile global coalition. The most delicate negotiations involved the Arab states, who had to be prevented from supporting their brother dictator, and above all, the Syrians were to be bought off at all costs. But how could the Americans possibly treat with the butchers of Pan Am 103? Just as the diplomatic process was becoming hopelessly entangled, rescue came in the form of “new forensic evidence,” which showed that the Syrians were in fact innocent, and the actual culprits were (so conveniently) the Libyans! Honor could be satisfied, the Syrians mollified, and another atrocity laid at Colonel Qaddafi’s doorstep.

Who controls the present controls the past; who controls the past, controls the future. Power gives one the right not only to determine the messages transmitted in the media, but also to convince the audience that this reality has always existed, whatever contortions this may cause in the memories of individuals. If Americans had a better grasp of the differences between (say) Libyans and Syrians, perhaps they would be more disturbed by the ease with which one culprit yielded place to another, with scarcely any admission that a change was in fact being made.

It is fascinating to observe the periods in which these transformations actually occur, in which states not only interchange particular friends with foes, but pretend that nothing has changed at all. This was evident following the Kuwait invasion, when the West suddenly discovered that Saddam Hussein (gruff strongman, firm but fair military figure, bastion of the Arab world against Iranian expansion) was in fact Saddam Hussein (New Hitler and paramount threat to the peace and prosperity of the entire world). And at precisely that point, the West discovered that Saddam controlled the terrorist hordes of the world, that Baghdad was in reality the center of this Evil Empire, and moreover—and this was the good part—that he and Baghdad always had held these positions. If it was not such a horrible story, this announcement would have occasioned hilarity among researchers in the world of terrorism, who had known this fact for over a decade, but who had been more or less forbidden to announce it.

In reality, Iraq’s track record in sponsoring terrorism and terrorist groups was always impressive, and perhaps the best known such group, headed by the semi-mythical “Abu Nidal,” has from its foundation been little more than an arm of the Iraqi intelligence services and mukhabarat, operating out of that nation’s embassies. When “Abu Nidal” gunmen were picked up by police, they could easily be connected with the local diplomatic mission. In 1982, Iraq claimed to break its ties with the group, in order to qualify for American aid, but no grownup observer ever believed that this notional severance meant anything. Through the Gulf War, whenever Saddam wished to put the arm on a Gulf state failing to pay contributions to the Iraqi war effort, the Abu Nidal group would predictably leap into action, and target that small nation’s airliners and diplomats until they were brought into line. For years, the only effective opposition to these thugs came from the much-maligned Palestine Liberation Organization, who tried forcibly to root out the Abu Nidal network whose crimes so tarnished the Palestinian cause. In return, the Iraqis exacted a terrible toll on the Palestinian leadership.

For a decade of scandalous silence, the West—and specifically the United States—did nothing to draw attention to the true origins of “Abu Nidal” atrocities because this would interfere with the crucial military and intelligence aid that Iraq needed to survive its war with Iran. If Saddam went down, the dominant power in the region would be the Iranians, who— heaven knows—might be crazy enough to invade Kuwait. As the presidential boast went, Saddam was “our son of a bitch,” and he could not be seen to be involved with terrorism. No intelligence agency therefore pointed out the solid-to-overwhelming evidence that connected the Iraqis to countless horrors like the Istanbul synagogue attack and a string of anti- Jewish massacres and attempted massacres around the world. Interestingly for recent events, the Iraqis also appear to have been the major sponsors of the Abu Ibrahim network, which from about 1982 onward perfected the bomb-planting tactics which brought down several civilian airliners. Hmm.

The policy of official neglect was understandable, if craven, but the real mystery comes in the attitude of the American “news” media, which virtually never challenged the story they were hearing from the administration and the collective spooks. One of the honorable exceptions was Judith Miller herself, who discussed Iraqi complicity in terrorism in the mid-I980’s in a number of stories with ramifications that were never explored by her peers. In retrospect, it is sickening to read the various accounts of the “terror network” promulgated throughout the decade, in which Iraq appears only as a victim of that great bogey International Terrorism, and Saddam is portrayed as a target of Islamic extremism, quite as much so as the people of New York, London, or Paris. After all, had he not broken his ties with the Abu Nidal group? Well, he said he did, and that’s good enough for us.

Throughout the 1980’s, the media served as what Orwell aptly characterized as double-plus-good duckspeakers, performing an outstanding job in uncritically quacking forth the opinions fed them by officialdom. In so doing, they never acknowledged (or God forbid, even noticed) that the material they were recycling represented a strongly ideological and self-interested position. The vast bulk of evidence emerging from official and intelligence sources. Western or Israeli, had as a prime goal the denunciation of Syria, Iran, and Libya, while Iraqi activities were essentially ignored. Official, media, and fictional accounts combined to create a self-sustaining myth, of three and only three members of the “terror cartel.” Essentially, the neglect of Iraq must in part be attributed to the laziness of the media in failing to check official assertions. Conversely, when Iraq became a prime enemy after the Kuwait invasion, the abundant evidence of Iraqi terrorism was made available to such an extent that his Ba’athists now appeared virtually the only significant lords of terror. In constructing Saddam as a major enemy in the months leading up to war, it became as necessary to magnify his past activities as systematically as they had been played down in previous years. There even began a process of retroactive demonization, attributing to Iraq guilt for earlier incidents which had hitherto been associated with other nations or culprits.

The stigma associated with a terrorist state cannot therefore be explained either in terms of the nature and extent of its illegal activities or the degree to which its crimes are known to law enforcement agencies and the media. In large part, it reflects the diplomatic position of that nation, and its usefulness or danger to other countries with powerful diplomatic establishments and media. In the context of Western perceptions, this inevitably means that the changing attitudes of particular American administrations will decide which states will be demonized. The definition of terrorism is a highly political phenomenon, a subjective, complex, and often self-contradictory process, and common perceptions to the contrary, the stigma is applied in a thoroughly selective and partial way. If we really had an adversarial press, the public would know this.

Leave a Reply