It’s understandable why Blue Road: The Edna O’Brien Story, was ignored by feminists, even though the film was screened in March, which is Women’s History Month. Blue Road was shown not as part any feminist program, but as a feature in the annual Irish Film Festival at the American Film Institute’s Silver Theater outside of Washington, D.C.

The film doesn’t fit in the typical feminist syllabus because Edna O’Brien, despite being one of the great female writers of the 20th century, was too brilliant, too funny, and too complex to be considered an orthodox feminist. As David Rooney put it in his review of Blue Road for the Hollywood Reporter:

While her early novels chimed with the nascent 60s feminism, O’Brien, like Doris Lessing, was ‘no darling of the feminists,’ as she put it. Instead, she insisted that what she regarded as the fundamental differences between the sexes most interested her as a writer: ‘Of course I would like women to have a better time but I don’t see it happening, and for a very simple and primal reason: people are pretty savage towards each other, be they men or women.’

You won’t hear that kind of talk at Brown or Harvard.

Blue Road is a fantastic film, deeply stirring spiritually, literate, and with real emotional heft that is earned. It tells the story of Edna O’Brien (1930-2024), a vivacious, gorgeous, iconoclastic and gifted Irish writer. O’Brien was the last of four children, and grew up in a “one-horse, one-hotel town with 27 pubs” in County Claire. She moved to Dublin in the early 1950s and got a job writing a weekly magazine column. It was in Dublin that O’Brien bought a copy of T.S. Eliot’s Introduction to James Joyce. The book was for her transformative. O’Brien carried it with her everywhere. She realized she wanted to be a writer, despite the fact that, as actor Gabriel Byrne notes in Blue Road, the Irish literary community was “a male preserve.”

In 1954 O’Brien, 24, met the writer Ernest Gébler, who was 40, divorced, and a Communist. O’Brien’s family tried to stop the relationship, even riding to Gebler’s country home to try and remove O’Brien. It was too late. In 1960 O’Brien’s published her debut novel, The Country Girls. It was a huge success as well as scandalous in deeply Catholic Ireland, which was not ready for a novel by a woman who talked about the sexual desires and interior psychological lives of girls. O’Brien was accused of “corrupting the minds of young women.”

Here’s how she described her life at this time: “I felt no fame. I was married. I had young children. All I could hear out of Ireland from my mother and anonymous letters was bile and odium and outrage.”

O’Brien’s husband Gébler was jealous of his beautiful wife’s success, and the depictions of his rants and abuse in Blue Road are harrowing. Gebler demanded his wife turn over her royalty checks to him, out of which he would pay her an allowance. He wrote nasty editorial comments in her diary—excerpts are read in the film by Jessie Buckley—claiming that he was the real talent behind her books. O’Brien and Gebler had two sons, Carlo and Sasha, and both are interviewed in Blue Road. One of them characterizes their parents as “chemically unsuited” for one another. Blue Road, the title of the film, comes from the fact that Gébler jibed at his wife for using “blue road” as a description. That’s how petty he was.

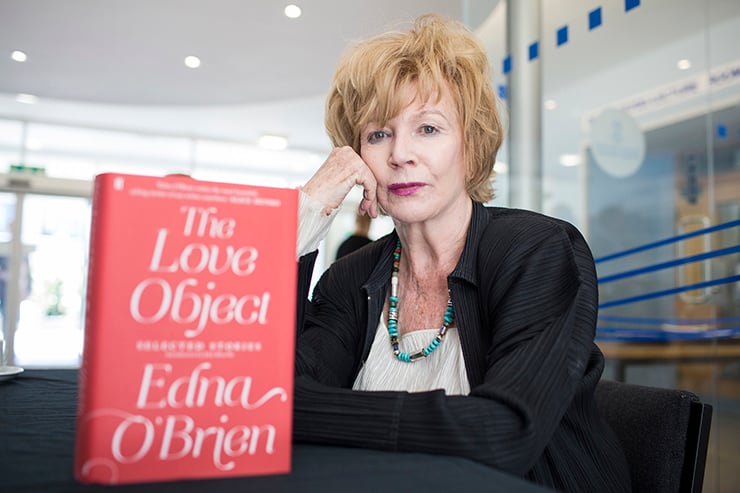

O’Brien eventually divorced Gébler and moved to London with her two sons—just in time for the swinging 1960s. A diligent writer, she produced a book a year—34 in all. Many were about Ireland, but O’Brien also had a wider range. The Little Red Chairs is about a Balkan war criminal, and Girl dramatizes the abduction of over 200 schoolgirls in Nigeria.

She wrote biographies of James Joyce and Lord Byron. She also experimented with LSD, afterwards producing a novel, Night, that was a dramatic departure from her usual style. “O’Brien was a writer with a capital W,” Lisa Allardice wrote in The Guardian when O’Brien died last year, “in the vein of her great heroes James Joyce and Virginia Woolf, but with wilder parties.”

In Blue Road O’Brien’s fierceness comes across in old TV clips and more intimate interviews conducted by the film’s director, Sinead O’Shea. The writer Ron Rosenbaum describes O’Brien as “one of those women whose perfect manners, executed with subtle grace, give her an unexpected power.” He goes on: “Despite surface delicacy, Edna O’Brien radiates a fierce and feminine energy, the kind of inextinguishably vibrant beauty that had suitors such as Marlon Brando, Robert Mitchum and Richard Burton following her wild red tresses through London in the swinging ’60s and ’70s.” O’Brien was also the friend of Philip Roth, Norman Mailer, and Saul Bellow. O’Shea also interviews Walter Mosley, Anne Enright, and Andrew O’Hagan who were all influenced by O’Brien’s work.

You’d think all of this would make Edna O’Brien a heroine in the eyes of feminists, but somehow it doesn’t. “It’s interesting that while the theme of women seeking freedom and love on their own terms ran through her work,” David Rooney observes in the Hollywood Reporter, “suggesting classification as an important voice in feminist literature, O’Brien never positioned herself that way. Nor did the feminist movement of the ’60s and ’70s appear to embrace her. While women writers including Louise Kennedy and Doireann Ní Ghríofa are among the film’s talking heads, there’s no mention of support from the prominent female authors of O’Brien’s time.”

The reason is that Edna O’Brien was too brilliant, too expansive, and too wise to be shoehorned into feminism’s dreary dogmatism. Her influences were not Betty Friedan and Andrea Dworkin, but Joyce, Hemingway and T.S. Eliot. In a conversation with Philip Roth in 1984, who called O’Brien “the most gifted woman now writing fiction in English,” she said: “Love replaced religion for me in my sense of fervor. When I began to look for earthly love (i.e., sex), I felt that I was cutting myself off from God.”

In one of the clips featured in Blue Road, O’Brien says this: “Men expect a woman to be a goddess, a whore, a mother and a breadwinner, so the only good thing about them is the occasional sexual pleasure they give us.” That sounds abrasive and unfair when taken out of context, but in the actual clip it is said with wit and irony and not meant to be the final word on the subject. The audience, the host, and O’Brien are all laughing at her brazenness.

O’Brien also loved Ireland much more than the spotlight of politics or the glamor of Hollywood. “It still baffles me how I came to know all these people,” she says. Near the end of Blue Road O’Brien says that while she enjoyed the elite and glamorous scene for a while, the most important moments in her life were those from her childhood: women driving cattle, her mother’s cough, and interacting with trees, fields, and nature. At one point her son Carlo Gébler notes that his mother was an incredibly hard worker—34 books, after all—and that like all great writers she was capable of “seeing all sides of an issue.” Today’s feminists, divorced as they are from the experience of just living their lives as women in the context of the larger reality of the world, are reluctant to see all sides of an issue—or to see people as complex rational beings with immutable characteristics. In a diary entry from May 1967, O’Brien wrote this: “Ah, the trees, how tortured they are. If anyone has to ask me about the Irish character, I say look at the trees. Maimed and stark and misshapen but ferociously tenacious.” There was nothing maimed or misshapen about O’Brien’s own appearance (she had a model’s looks), but she was absolutely tenacious.

Leave a Reply