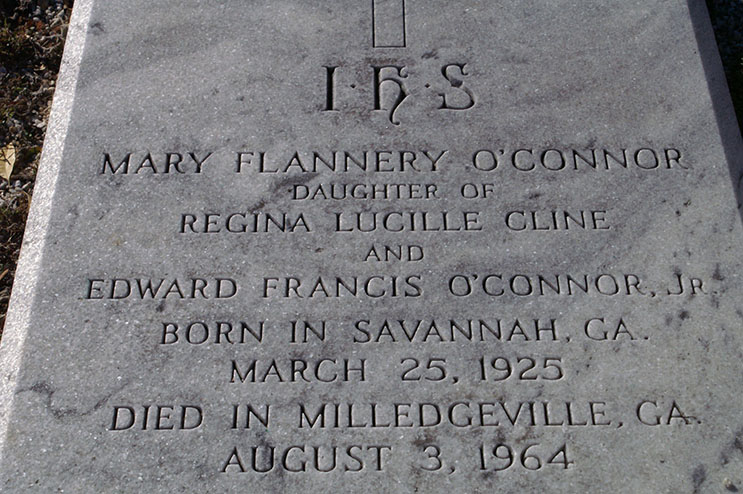

The subconscious search for bright lights in the dark city is a universal fact of human nature as we all wish to avoid pain. Yet, at the same time, our search for illumination is borne out of hope for something better. It sounds trite, but one must take the bad with the good. There’s no avoiding life’s tragic aspects, but there’s also no understanding the tragic without appreciation for the joy of life. Nobody knew this more than Flannery O’Connor (1925-1964), an American writer, whose prose still inspires Americans more than half a century after her untimely death.

O’Connor was diagnosed with lupus at the age of 25, and ultimately it was this disease that would claim her life. Her father, Edward, also died of lupus when O’Connor was just 15 years old. The illness and its severity (which would become more and more apparent as the years went by) forced her to move away from the East Coast and back to her family homestead Andalusia, in Milledgeville, Georgia, to live out the rest of her life with her mother, Regina.

Flannery accepted her occupation as a writer because she saw it as much more than an indulgence of a passion or a way to make a living—it was a vocation inextricably linked to her Catholic faith. “I write the way I do because (not though) I am a Catholic,” wrote Flannery in a letter to Betty Hester, dated July 20, 1955. Yet at the same time, she acknowledged that she was a “Catholic peculiarly possessed of the modern consciousness, that thing Jung describes as unhistorical, solitary, and guilty.”

Suffering was and is unavoidable, especially for someone in O’Connor’s condition. Yet this never stopped her from creating. In fact, it could be argued that her great physical suffering aided her in the creation of stories populated by saints and sinners alike.

O’Connor saw the troubles of the world and could easily conclude that it was falling apart but, then again, when was the world not falling apart? In the same letter, she criticized the increasingly atheistic society she and others were witnessing: “This is a generation of wingless chickens, which I suppose is what Nietzsche meant when he said God was dead.”

O’Connor easily could have ignored everything outside the walls of her Andalusia farmhouse. But her faith did not permit such an escape. If anything, she affirmed the existence of evil continuously through her stories. While she may have been an odd creature in some ways (as were many of characters) she was never sarcastic. In fact, it would be false to mistake O’Connor’s sharp tongue with hopelessness or cynicism. “… you have to cherish the world at the same time that you struggle to endure it,” she wrote to Betty Hester.

O’Connor’s stories are filled with what appear to be fantastical elements but the mystery of faith is both physical and mystical. Despite the supernatural elements of her faith, O’Connor remained firmly planted in the soil from which we all come. In some ways, the struggle is not so much the one to accept God but to accept the reality of both good and evil. O’Connor took evil seriously, and her understanding of it was not just an acceptance of some quaint, mythological story from childhood. During her time, and even more so today, people are viewing life in terms of primitive emotionalism. The prevailing “wisdom” of our time is that if something doesn’t feel good (or pleasurable), then the best thing to do is to avoid the responsibility of actually dealing with it.

In a letter dated Sept. 6, 1955, once again to Betty Hester, O’Connor wrote what would become an oft-quoted sentence: “The truth does not change according to our ability to stomach it emotionally.” If we read further, she reveals even more unflattering truths about the metaphysical direction in which American society, even then, was headed.

Criticizing Jean-Paul Sartre, who “finds God emotionally unsatisfactory in the extreme,” O’Connor hits back once again with reality of good and evil, something Sartre does not see in the same way at all. We are often creatures of contradiction, and as a short story writer and keen observer of the human condition, O’Connor was in a unique position to understand these contradictions from a variety of angles.

“A higher paradox,” writes O’Connor, “confounds emotion as well as reason and there are long periods in the lives of all of us, and of the saints, when the truth as revealed by faith is hideous, emotionally disturbing, downright repulsive. Witness the dark night of the soul in individual saints. Right now the whole world seems to be going through a dark night of the soul.”

In truth, however, evil does not favor a particular time. It simply exists. The ugliness of reality is visible every day, but so is beauty. That is what O’Connor alludes to when she speaks of truth. How can we then “cherish the world” that is filled with darkness, hatred, greed, and manipulation? What is there to cherish and what is the point of even engaging in such an active embrace when this ugliness is inevitable?

O’Connor is speaking of gratitude for life itself. How can the mind that sees beauty alongside evil give up on the world? For that matter, how can we allow the “culture of death” to expand when life gives us daily instances of order?

A positive change in society can only occur when people choose to embrace the yes of life, and this is a choice we must make anew each day. Sadness and melancholy may follow us like the burdensome shadows they are, but despair ends in wallowing in those shadows, often leading to an exit that unhappy and permanent.

Fellow writer Walker Percy understood this existential dread that follows many people. It’s what led him to say that a writer must be “an ex-suicide,” every day. Each day is one of choosing to see life face-to-face. As Percy said, “One feels, What the hell, here I am washed up, it is true, but also cast up, cast up on the beach, alive and in one piece … The possibilities open to one are infinite.”

This attitude is not just one of psychology but also one of faith. To be free in such a way requires a complete metaphysical surrender, and easing into the knowledge that we are not the beginning or even the end of things. And surely, we can thank God for that.

Leave a Reply