From the June 2010 issue of Chronicles.

Two politicians get conservative fundraisers’ juices flowing like no others. One, the late Sen. Edward M. Kennedy, was surely mourned as much by ambitious Richard Viguerie imitators as by teary-eyed, Camelot-addled liberals. The other, former Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin, they hope will be a gift that keeps on giving for many years to come.

Conservatives built a virtual cottage industry of Kennedy-mocking paraphernalia. There were bumper stickers proclaiming, “My gun has killed fewer people than Ted Kennedy’s car.” There were T-shirts identifying the wearer as a student at the “Ted Kennedy School of Swimming.” No defense of Richard Nixon was complete without the phrase, “Nobody drowned in Watergate.” And when the Chappaquiddick jokes finally grew tiresome, there was no end to the fun that could be had by ridiculing Kennedy’s improbable combination of corpulence and philandering.

Sarah Palin does not have any of the later-year Ted Kennedy’s problems with physical attractiveness. After she burst onto the scene as John McCain’s running mate in the last election, she emerged as something of a sex symbol for middle-aged conservative men. Her smiling, bespectacled face graced magazine covers. The late-night television talk shows were filled with bawdy references to the vice-presidential candidate as a “hot” schoolteacher or librarian. Now that she is mainly a conservative celebrity, Palin has taken up residence on those talk shows herself, joking about doing an impression of former Saturday Night Live cast member Tina Fey.

Kennedy and Palin do not merely get conservatives exercised, however. They attract equal and opposite reactions from liberals. Liberals adore Ted Kennedy as a dutiful son in America’s royal family. They identify with his “dream” that “shall never die.” In him, they see their ambitions for socialized medicine, massive antipoverty spending programs, and a national economy totally restructured along egalitarian lines, until every oppressor is brought low by an ever-expanding list of victims.

Sarah Palin, by contrast, is an object of liberal scorn and condescension. She is said to represent the dumb, Bible-thumping, trailer-trash school of conservatism that threatens to transform our secular, cosmopolitan republic into—as one anti-Republican e-mail chain from the aftermath of the 2004 presidential campaign memorably called it—“Jesusland.” The Palin of ferocious liberal imagination is censorious, fundamentalist, and, as the former conservative journalist David Brock once said of Anita Hill, “a bit nutty and a bit slutty.”

What did these two figures do to elicit such adoration and derision from their respective supporters and detractors? In Kennedy’s case, it is easy enough to see. During his long, productive career in the Senate, he helped obliterate the country’s borders, unleash a stream of uninterrupted mass immigration, harden antidiscrimination laws into racial quotas, incrementally expand federal control of healthcare and education, massively increase spending while putting commensurate upward pressure on taxes, and legitimize liberal Catholics’ support for abortion on demand and the abolition of the traditional family.

Even much of the good Kennedy did—such as using his high-decibel voice to speak out against the occasional unjust war—was mitigated by his rank partisanship. When Vietnam was his brother John F. Kennedy’s war, Teddy shouted doves down with the contempt he would later reserve for Jesse Helms: “I wish they had raised their voices against Viet Cong terrorism, against Viet Cong murder, kidnapping, and political assassination.” He further argued, “Any facilities in North Vietnam strengthening the Viet Cong should be bombed.” Kennedy was seldom a peacenik during the conflicts Bob Dole crankily described as “Democrat wars”; he tended to be antiwar mainly under Republican commanders in chief.

But one man’s trash is another man’s treasure. To millions, the above record was the good Kennedy did. If you are unbothered by the demographic, cultural, and economic transformation of your country and prefer elaborately decorated senior citizens’ centers in your hometown, courtesy of Uncle Sam’s generosity, Kennedy may indeed be your hero. And Kennedy’s rhetoric did channel much of what is decent about modern American liberalism: its compassion for the poor and downtrodden, its trepidation about military force, its genuine concern for the treatment of blacks and other groups that have been marginalized in our society (except when they, like unborn children, cannot vote).

It is a bit harder to see why people get so worked up over Sarah Palin. She is a professed Christian, a family woman, and a hunter, and she did not abort her own children or encourage the abortion of her grandchild. All good things, to be sure, but in other times they would not have been the stuff of heroism or villainy. As a politician, she was briefly mayor of the small town of Wasilla and then even more briefly the governor of Alaska, before joining the folly that was the 2008 McCain campaign.

Palin perceived that the Alaska Republican establishment, led by unpopular then-governor Frank Murkowski, was falling into disfavor. So she ran against that establishment in 2006, helped dislodge Murkowski in the Republican primary, and extended the GOP’s control of Juneau in a difficult political climate. Similarly, she was quick to determine that a congressional earmark for the Bridge to Nowhere—which she once supported, holding up a pro-bridge “Nowhere, Alaska” T-shirt—was a fiasco in the making, so she adroitly pivoted on it. If all of this seems like rather thin grounds for becoming simultaneously the most hated and the most beloved political figure of our time, well, that’s because it is.

During the 2008 campaign, Palin briefly breathed life into the moribund Republican ticket. She was everything McCain was not: energetic, effective on the stump, beloved by grassroots conservatives, and lifelike. She single-handedly derailed former Republican congressman Bob Barr’s hopes of siphoning a significant share of the conservative vote, turning him into a typical Libertarian also-ran. Palin shone in her speech at the Republican National Convention, and it briefly looked like she was going to pull off the impossible: mobilize rank-and-file Republicans while drawing in enough disaffected Hillary voters to make the presidential contest a competitive race again.

But this was a lot to expect of a neophyte on the national stage. Palin’s subsequent media appearances ranged from middling to catastrophic. She seemed unprepared and ill-informed in high-profile interviews. Then her running mate reacted to the financial meltdown by suspending his campaign, embracing the bipartisan Wall Street bailout, and otherwise acting like a crazy person. It was over.

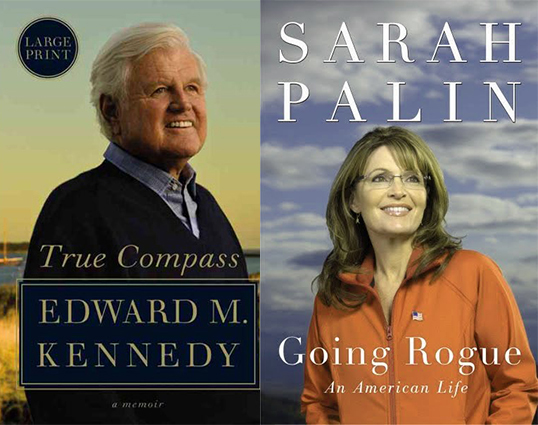

Whatever their contributions to our politics, Sarah Palin and Ted Kennedy have both seen fit to add contributions to our literature. Palin’s Going Rogue: An American Life may be a campaign autobiography, or it may be an attempt to extend her 15 minutes of fame. Kennedy’s True Compass: A Memoir is the posthumously published swan song of a public figure. Neither is a great book, containing all the flaws and political score-settling endemic to the genre, but both succeed in demonstrating each “author’s” virtues, as well as mistakes.

Though the bumper-sticker manufacturers would never admit it, Ted Kennedy actually had some conservative characteristics: a rootedness in a particular place; a fidelity to specific institutions, traditions, and people; and a sense of kinship and community. Unlike Martha Coakley, who tried to replace him in the Senate, Ted Kennedy would never have mocked an opponent for campaigning outside Fenway Park in the cold before an election. He would not have smeared legendary Red Sox pitchers as Yankee fans. Kennedy stubbornly clung to his Boston accent his whole life. “The state and city of my birth are extensions of myself and my family,” he writes in True Compass. Yet Kennedy’s expression of his rootedness also reveals his emotional orientations: Note that he sees the state and city of his birth as extensions of himself and the Kennedys, not the other way around.

This is how Kennedy was able to win so many votes from people who disagreed with him about tax cuts, abortion, immigration, forced busing, and countless other issues: They sensed that, however rich and powerful he was, his appreciation for their shared customs and traditions made him one of them. Voting for Kennedy was like attending Mass, eating clam chowder, and cheering a Red Sox home run. Yet Kennedy used his cultural solidarity with the residents of his state and city to lord it over them.

As Matthew Richer observed on VDare.com, “New England has always been a region of ‘little platoons,’ where people proudly retain their local customs and accents.” But because of the Yankees’ egalitarian politics and the white ethnics’ own immigrant backgrounds, New Englanders were slow to appreciate the cultural impact of mass immigration unaccompanied by assimilation. Moreover, while serving as floor manager for the disastrous 1965 Immigration Act, Kennedy took care to withhold from his constituents information that would inevitably have aroused their concern. Instead, Kennedy, then chairman of the Senate’s immigration subcommittee, proceeded to give the American people a list of “What the bill will not do”: “First, our cities will not be flooded with a million immigrants annually. . . . Secondly, the ethnic mix of this country will not be upset.” The results are now in, and Kennedy was wrong on both counts, if he ever even intended to be right.

Nevertheless, True Compass is animated by the universalist Kennedy’s love of the particular: his parents, his brothers, his children, his compound, and his boat. Even the Catholic Church appears as an object of Kennedy’s affection. But his was a strange Catholicism, completely divorced from God, Scripture, and the sacraments and seemingly based on a view of his Church as a cultural artifact. The book’s one notable reference to the Bible occurs when Kennedy tries to tie his salvation to his liberalism:

My own center of belief, as I matured and grew curious about these things, moved toward the great Gospel of Matthew, chapter 25 especially, in which he calls us to care for the least of these among us, and feed the hungry, clothe the naked, give drink to the thirsty, welcome the stranger, visit the imprisoned. It’s enormously significant to me that the only description in the Bible about salvation is tied to one’s willingness to act on behalf of one’s fellow human beings.

This second sentence is as self-serving as it is wrong, and it is conspicuous that Kennedy doesn’t identify the “he” who is doing the calling as Jesus, Who goes unmentioned throughout True Compass.

In Going Rogue, Sarah Palin, by comparison, invokes God unashamedly. She speaks frequently about the content of her faith, the Bible, church, and prayer chains. She even recounts some of her own personal prayers: “I sat down on the grass and prayed, ‘God, thank You. Thank You for Your faithfulness . . . always seeing us through . . . ’” Like Kennedy, she connects her religion and her politics. Palin recounts telling Alaskans in her first address to them as governor, “More government isn’t the answer because you have ability, because you are Alaskans, and you live in a land that God, with incredible benevolence, decided to overwhelmingly [sic] bless.”

Sarah Palin’s opinions regarding constitutionally limited government are generally sound. She writes that “national leaders have a responsibility to respect the Tenth Amendment and keep their hands off the states,” while, as a budding decentralist, she believes that “local government is best able to prioritize services and projects.” This she calls “the basis of the Tenth Amendment.” But the distant Capitol that cannot be trusted to manage the affairs of Alaskans or Arizonans seems to her infinitely wise and benevolent when it comes to nation-building for the Iraqis, the Afghans, and, presumably, the Iranians. “Today our sons and daughters are fighting in distant countries to protect our freedoms and to nurture freedom for others,” Palin writes. “I understand that many Americans are war-weary, but we do have a responsibility to complete our missions in these countries so that we can keep our homeland safe.”

“We are both the world’s sword and its shield,” she continues.

[W]e lend not just our strength but the support of a free people to others who are fighting for their freedom. They need to know that America is not indifferent to their struggles but will lend her considerable diplomatic power to their cause. Nations like Israel need to be confident of our support.

In respect of the republic versus empire debate, Palin adds,

Some people ask whether we are still a republic, or whether we are becoming an empire, doomed to fade away like all the other empires once thought to be invincible.

We are still a republic. We are certainly not doomed to fade away. And we have no desire to be an empire. We don’t want to colonize other countries or force our ideals on them. But we have been given a unique responsibility: to show the world the meaning and the rewards of freedom. America, as Reagan said, is “the abiding alternative to tyranny.” We must remain the Shining City on a Hill to all who seek freedom and prosperity.

Millions of conservatives sympathize with Sarah Palin because she is so much like them: a woman of decent and normal impulses in favor of faith, patriotism, and regional pride. They are the Americans (like Palin’s son Track) who proudly wear the uniform of this country and fight in its wars. They are the ones whose taxes finance the welfare-warfare state. But their values make them susceptible to the appeal of American exceptionalism, through which ideologues and opportunists gain power by persuading good-hearted people to support unnecessary wars and the indiscriminate election of Republican politicians.

The Tea Party movement, in which Palin is active, is a case in point. What began largely as a citizen reaction to the growth of the federal leviathan is already being taken over by Republican hacks and neocon pamphleteers. The process is much like that by which Palin herself, in a little more than a decade’s time, went from being a member of the Buchanan brigades (she recently said that she first learned of Richard Pipes’ call to bomb Iran in a column by Pat Buchanan) to being Randy Scheunemann’s foreign-policy pupil.

While True Compass and Going Rogue contain much of interest, both books are ultimately stories of how the political class takes what is good and true to gin up enthusiasm for a two-party system that too often resembles a sporting event between the red team and the blue team.

[True Compass: A Memoir, by Edward M. Kennedy (New York: Twelve) 532 pages, $35.00]

[Going Rogue: An American Life, by Sarah Palin (New York: HarperCollins) 432 pages, $28.99]

Leave a Reply