With the falling leaves and falling temperatures, hordes of newspeople looking for the hungry and homeless descended on the missions and the shelters. Now collectively called Street People, Streetniks (my term) became the “darlings of the press”; every day, in every paper, we are brought up to date about them. USA Today for example, recently featured a run-down of their problems, including a photo and a quotation from a “representative” of the homeless from each state—subjective photo journalism and human-interest stories were substituted for objective investigation.

As a teacher, I could not critically discuss the topic with my students, lacking reliable data, reliably collected. As a social investigator, once again I hit the road—or better said, the street.

Easy Street? There were at last count 41 meals served every day to Streetniks in Nashville. If they care to, they can spend all day eating. All you do is line up and eat. No questions asked. No one who wants a warm place to stay is turned away. Easy living? Here is a list of things I got, saw, received, or are advertised as available free for the asking: food, snacks, food to go, clothing, shelter, towels, blankets, soap, personal items, gloves, ski caps, razors, aspirin, cold tablets, Band-Aids, eyeglasses, medical care, prescriptions filled regardless of issuing doctor, emergency medicine, stitches. X-rays, crutches, false teeth, dental care, alcoholism treatment, sermons, sing-alongs, friendship, companionship, opportunities for exercise, walking and strolling, Christmas carols, writing materials, pens, envelopes, stamps, Christmas cards, fruit cake, daily newspapers, magazines, diapers, sanitary napkins, baby food, neck braces. Ace bandages, etc.

Hard living? In a single week, two street people were stabbed to death within four blocks of each other. One stabbing occurred in the chapel of the Mission, in the corner where I slept three weeks earlier. Also, a ferocious knife fight took place on the steps of the Mission while I was standing there. My notes of the brawl say that the brawlers were too drunk to fight dangerously but not too drunk to kill each other with knives (that is, unknowingly).

Streetniks are also doing time—they have to become skilled at doing nothing, all day, every day. The vast majority smoke, and cough. While you will see a fat one every now and then, most are lank if not thin. The only really skinny ones I saw were mental cases.

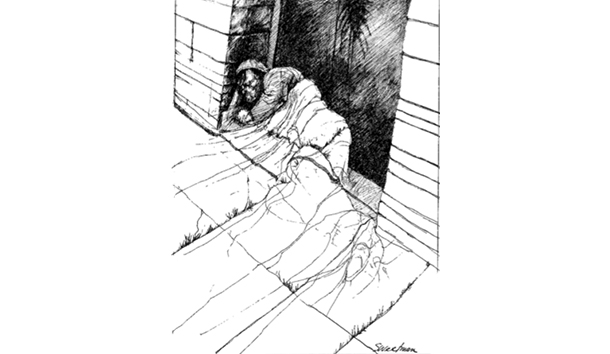

It was about 9:00 on Saturday night, and I was huddled in a corner of the chapel at the Mission, on the tile floor, wrapped in a scratchy blanket I got with my attendance at the “service.” Three preachers preach and lead singing of hymns from the songbooks that are passed out at the beginning of each service. For that you get supper and a place to lie down—sleeping is another matter. The smell and the sounds kept me fully awake most of the night. I can’t describe either because I have no comparison to make. I cannot exactly remember the smells and sounds of barracks full of sailors and marines a third of a century ago, but they could have been nothing like these smells and these sounds or I would have lost my mind—or gone AWOL.

It was like one large animal made up of many small parts; all of them were constantly moving and making noises, ranging from soft and smooth to sharp and grating.

The smell was sickening; luckily it diminished in force. I could taste the air as I have tasted the smells on the street of Mexico City—there, a mixture of exhaust fumes and tacos. Around daybreak I dozed off for a while; then it was time to clear the chapel. We put the chairs back in rows and got ready for breakfast.

It’s exactly one block to “Sally” (the Salvation Army). Breakfast starts at 7:30. It was 28 degrees with a light fog and low-lying clouds hiding the top of L&C tower. Willie, however, didn’t notice. He was intent on getting in line and eating. He walked with that characteristic shuffle—head slightly bowed, shoulders sagging, and feet barely clearing the pavement.

Willie had drunk two pints of Thunderbird late yesterday evening and felt bad, plagued by diarrhea, a common by-product of fortified wine. Music City Liquor Store is the attraction of Lower Broad to Willie, its proximity to historic Ryman Auditorium notwithstanding. The store specializes in fortified wine at $1.25 a pint with 20 percent alcohol. Willie would have to drink over five cans of beer at $1.00 a whack to get the 3.2 ounces of pure alcohol they pour into a pint of cheap wine produced expressly for Streetniks.

There were 22 in line when Willie got there. They all looked a great deal like him. Breakfast. There are only two workers this morning—one. Pop, a regular employee of Sally who came off the street for the job some time ago. Pop was putting two pieces of white bread on a rather flimsy paper plate, spooning gravy over them and handing the plate to the men. Willie got his own plastic fork. The other worker beside Pop was partly, and sloppily, filling styrofoam cups with coffee from a big thermos and handing each man a doughnut. Willie and the others were eating in an annex the Army had acquired to meet the needs of the burgeoning crowd. Long temporary tables were covered with paper tablecloths, overlapped to cover the tables completely. Chairs were at a premium, and pew-like benches were used for one side of the back two tables.

It wasn’t too bad for Willie. The gravy was pretty warm and went down smooth compared to the Thunderbird. There were no napkins, but if there had been, Willie would not have used them to wipe the spots of gravy off his untrimmed beard. In a swiping motion, he used the palm of his hand, which he then wiped on his pants leg. Not a word passed between Willie and his breakfast companions. He ate everything on his plate, put his doughnut in his jacket pocket, picked up his plate and empty coffee cup, dropped them in the garbage can by the door, and hit the streets. Again. Long time till 11:30.

As he walked up Demonbreaun Street and then over to Broadway, Willie was unaware that the fog had lifted, that the tops of the downtown buildings were visible, or that the sun was shining.

Storefront Ministry was open, but Willie couldn’t get in. Because of nice weather they were going to give out the lunch tickets on the sidewalk in front, so he waited some more. He had spent a lot of time in SFM last week, waiting for clothes, talking and smoking, until they put up that no smoking sign.

Here they come with the tickets. Even though they give out tickets, Willie had never seen anyone turned away. The line snaked up Eighth Avenue, turned left, went down a block, came in the basement of the parish hall at Christ Church Episcopal. There they took Willie’s ticket, handed him a bag lunch, and he sat down. There was a cup of hot chocolate by each place. In the bag: a styrofoam bowl of veggie soup, chicken salad on light bread, banana, and chocolate cake. Just as Willie began eating, a big black man said, “Let us return thanks.” So Willie stopped (but did not take his stocking cap off, neither did anyone else, since “the man” did not tell them to) and then commenced eating again.

Finished, Willie got extra hot chocolate. He put his banana and a piece of chocolate cake he picked up from the table in his jacket pocket for later. On the steps leading from the basement back to the street, there was a nicely dressed man in an overcoat shaking everybody’s hand and saying “Merry Christmas.”

Since it was only 12:00, Willie went back into the chapel. He pulled four chairs together and snoozed a while. (Many others did the same thing.) The noise didn’t bother him much, and he slept till about 3:30. There is no mooching money to be had on Broadway—too much competition and too much resistance. He wandered over to Church and Second last week, made a killing off those folks in the fancy district, but was run off by the bulls. They said, “Hey fellow, get over there on Broadway where you belong.”

Supper was soup, as he knew it would be. A soup line, that’s what it was. But the soup was not bad. It was tasty hot onion soup. And light bread. Always light bread. Never any other kind. But that’s the only bread fit to eat, anyway. An apple for later.

Willie lucked out tonight. He had drawn the last bunk upstairs. Before he went to bed upstairs in the Mission, the best place to be because of the soft double-bunks with sheets, Willie ate his banana and chocolate cake and apple. And thus Willie finished his menu for the day. About 2,900 calories; 300 more than necessary to maintain his relatively inactive 170 pounds. Willie wore a very colorful ski cap, a T-shirt advertising Coors, two long-sleeved shirts, a brown nylon jacket with four big pockets (in one of which was a pair of blue cotton gloves), two pairs of pants, three pairs of socks, and a pair of two-toned leather loafers with built up hard-leather heels. All the clothes and accessories were given to him, most within the last few days.

The Mission, the Sally, Storefront Ministry, the churches, East Nashville Co-op, Ladies of Charity, and Metro Schools Clothing Room supply clothes free. Willie has been to most of them. The SFM has a “clothes person” as they do a “food person” and a “shelter person.” There is more clothing than anyone realizes—churches play musical clothes, calling on the places they think might need them so they can get rid of the stacks and hangers and mountains of clothing in their basement and make way for the never ending flood of apparel from caring parishioners.

The deluge begins in subdivisions and rural areas where the clothing is collected by agencies and churches, bundled and moved toward bigger towns, filling basements and storage rooms, growing and collecting until it all flows into Nashville. Here all the clothes, large and small, tops and bottoms, new and old, are sorted, bundled again, and taken to the dispersal points where staff and volunteers hand them out. At SFM the needy are signed in, lined up, and interviewed by the “clothesperson” before getting their new clothes, in first come, first serve, take-what-you-like fashion. And so the output of the clothing manufacturers here and in Taiwan, South Korea, Mexico, and a host of other countries finally passes into the hands of Streetniks. The clothes are useful again. But not for long.

The remainder of the journey of the suit that Willie gets, once worn with pride and care, is the saddest period of its life. After its owner outgrew it, either physically or fashionably, he carefully took it to the church when they had the Clothes for the Needy Drive. It had been handled with care until Willie got it. Like the Commandant at Dachau to his charges, Willie is likewise expected to apply the Final Solution to all his clothes. The suit stops here. As do all the clothes Willie and his fellow Streetniks receive.

There are no washing machines. There is no soap for washing. Streetniks are not allowed to bring them back to the agency that gave them away. Indeed, they are expected to abuse all the clothing and then discard it, much of it cleaned just before distribution. The suit and shirt and the pants and the gloves and the stocking cap will be worn for a while, quickly become filthy, and then be thrown away, often for someone else to pick up and dispose of properly. The men’s room in the federal building, alleys, bathrooms, street corners, just about any place downtown in any large city is littered with discarded clothing. After years of puzzling over where all our apparel finally winds up—somewhat like the search for the elephants’ graveyard—I found it in the garbage cans of Nashville. Hic jacet jacket.

At Holy Name Catholic Church I suddenly realized that all the homeless were not actually homeless if you count pickup trucks with campers as homes. As I was loitering around the steps waiting to go into the parish hall, I saw that the folks who were getting out of the pickup-camper—two white men and a white woman—were coming to eat also. Then I remembered that I had seen (but not registered) other Streetniks and cars. On Saturday as I was standing on the corner of Sixth and Demonbreaun, by the Mission, I noticed a nice looking car parked in the lot across the street. Two black men stepped out of it and went into the Mission. In a few minutes they came out with another black man, got in the car and drove away. Later I saw all three of them in the chow line at the Salvation Army. So there are cars—and trucks—available to some of the Streetniks if not actually owned by them. I rather suspect that some of the street crowd is made up of locals, without work and responsibilities, who come and go with the Streetniks. They pass the time, eat, get whatever is being handed out free that day (and there is a lot of that), and generally enjoy themselves. With cars they can be wherever the action is.

After the men and the woman went in the parish hall I toured the parking lot. There were six cars that appeared to belong to the folks inside; four were later driven off by groups of the satisfied luncheon crowd.

The hall was ready for us. All of the tables, except for the four in the very back, had from two to six people already seated. There were three rows of tables running from front to back of the hall. They were big tables with white disposable paper tablecloths, each seating eight persons. Coffee was in a large urn on a table to the side of the door with the usual “fixings” scattered alongside. A stainless steel countertop separated the hall from the kitchen. On this the “volunteers” were placing the big pans of food that would soon be passed out. The first worker in line was stacking a huge pile of serving trays. These were of the old-fashioned kind that had different shape and size cavities, which the servers filled with solid and semiliquid food.

I got a cup of coffee and sat down. The coffee was of an unusual color. I chose a table with a lady at one corner and two very bearded men at the other end. I sat across from the lady who appeared to be copying from a book into a notebook. I took a sip of the strangely tinted coffee and exclaimed to my tablemates, “What kind of coffee is this?” No one looked my way. Then quietly and without turning his head, the most bearded and the most tattooed of the men said, “Free.” End conversation.

Most Willies are white. But in Nashville, at least, there are also many blacks. Again, no surprise. You would expect groups to be represented on the street in proportion to their share of poverty and economic marginality. So you find many whites, many blacks, Hispanics, and Native Americans. A real polyglot, the street is also the true melting pot. But then it struck me: there were no Asian Willies. I saw Asians everywhere I looked—in stores and shopping centers and parking lots and grocery stores. I saw them working as clerks and packers. But I saw no Asians on the streets or in the shelters or in the food lines. They, among all minority groups, have few advantages to offer the strange American system. There is a relatively large number of them around. Yet, I found none on the street. Why? I suspect the answer to this question would go far in serving as the basis of a sane policy for our communities.

Except for a handful of articles in journals almost no one reads, I have never seen any objective studies of hunger and homelessness. Social scientists who stress methodological rigor react completely emotionally to the issues. Yet, not only did much of the pioneering work in sociology and social work develop in direct response to the needs of the destitute, but the empirical study of poverty has been a major subject in these disciplines. Mountains of research have accumulated, and methodologies have been sharpened. Still, none of these objective technologies are applied to current studies.

It seems reasonable that sociology and social work would include detailed contemporary studies of street people. But they don’t. The sad news is that our students are acquiring all their information from TV and the daily paper. We then send them out to administer programs aimed at helping a group of people they completely misunderstand, and to recommend therapy based on a false diagnosis. If medicine were practiced that way, most of the patients would die.

If the street people are to be aided, we need accurate information collected and shared—something more than a TV special called The Streets of Despair or a study by the State HHS Department indicating that “35-40 percent of those persons seeking shelter have suffered recent economic setbacks.” Regardless of some anecdotal remarks to the contrary, the street folks come from the lower class, and always have. It now appears from the small number of valid studies done about 1980 that two factors, often in combination, propelled onto the streets those who would have remained in a “stable” status otherwise. These powerful and devastating social forces are family dissolution and alcohol abuse. So long as the low education/few skills part of the community could share resources with a caring family, they could generally make it. But with divorce, remarriage, desertion, moving-in—the currents of family dissolution for a decade now—they end up with no one to turn to for support, in good times or bad. For example, I went with a newfound street buddy to Traveler’s Aid for him to get a bus ticket to Georgia. The agency was very willing but just wanted the telephone number of someone at the destination, to verify that my friend had a place to come home to. He could not give them one, even though he told me later that three of his grown children by his first wife, his mother (who was deserted by his father), two brothers, and a sister all lived there. If current trends continue, this destabilization of the family will sweep onto the streets an even greater number of the disadvantaged in every community in the land.

In the mid-70’s the number of patients in public mental hospitals in the state of Tennessee was about 7,400. At last count it was 1,300. Now, 6,000 persons did not get well. Nor did the 5,000 new cases of severe mental illness reported since the mid-70’s. In the first instance they were transferred to the street, then to jails, prisons, and nursing homes. Many made the ultimate trip—from the institution to the streets, then to the cemetery. They were really deinstitutionalized. Members of the second category are roaming the streets of our communities, sometimes armed with knives and guns.

A recent inquiry revealed that 63 percent of the nation’s chronic mentally ill are at large in the community. Still, funding for the states’ mental health resources hasn’t diminished. Unfortunately, the money hasn’t followed the patients. The inequity of care is reflected in the upward spiral in the staff-to-patient ratio which now exceeds 1.5 to 1 in public and private mental health hospitals nationwide. That means that there are 150 staff members for every 100 patients. I do not know what the ratio is in Tennessee; it would be a telling statistic.

One of the saddest sights I frequently see on the streets is an obviously mentally ill person struggling among the horde, confused and alone. Some know not what they need nor where to get it nor how to use it even if it is forthcoming. Trying to stay warm, huddling in the most likely places, they have been tagged the “Grate Society.” Even so, I have heard social workers take pride in being part of the movement which emptied the mental hospitals.

The Nashville Union Rescue Mission has become the largest mental institution in the state. There are more severely mentally ill roaming its halls and sleeping in the corners of its rooms and on its floors than in any other single place in the state. The old-line bums and winos no longer gather there—it’s too crazy and dangerous.

According to the best evidence I am able to collect, there are Streetniks only in the central cities of the four largest metropolitan areas. Why, for example, aren’t there street people in Murfreesboro? Murfreesboro is one tenth the size of Nashville. It should have one tenth the number of homeless—if Nashville has 2,000, that would be 200. If Nashville has 900, that would be 90. Yet Murfreesboro has none. Neither do any of the other medium-size and small towns in Tennessee. The answer is simple: there are no services for the homeless in Murfreesboro. As soon as services are established, there will be street people. It’s called “symbiotic relationship” by community ecologists.

It is the “critical mass” concept. Already there are people barely hanging on, as I pointed out earlier—but they are hanging on. With the establishment of street services, social fusion would occur, pulling the weakest loose from the fabric of the community onto the pavement. The stage is set for growth of the street persons to the limit imposed by the community. The greater the services, the larger the number.

As reliable firsthand information about the Streetniks accumulates, it becomes clear that there are at least three main groups of people on the street. Two of these groups cannot be helped and prevent well-intentioned but poorly aimed aid from reaching the remaining group, which is the only one likely to be positively influenced by the sort of help offered them.

The most pressing priority is to identify and remove the seriously mentally ill to settings where they can receive help. This should be easy to accomplish both physically and financially. Many of these unfortunate people in Nashville are already sleeping in a bona fide mental hospital. As part of the effort to get them off the streets in freezing weather, a project named “Emergency Shelter Plan” buses them to various places in really cold weather (20 degrees Fahrenheit), one of these shelters being the Middle Tennessee Mental Health Center (the old Central State), where, in all probability, some of these nightly visitors once stayed in warm surroundings around the clock.

Next the alcoholics. We have been keeping close watch on this group for many reasons for 30 or more years. The jury is in: not many get well. Period. With the best of care and support the odds are stacked against them. Out of every 35 alcoholics one gets well, the other 34 “just simply die.” Check the records of VA, the Koala Centers, or the Care Units. The results of a $10,000 private treatment are not encouraging.

Attentive companies have commenced employee assistance programs which offer help to their employees with drinking problems, providing they sober up. Otherwise, they are told to look for other work. Also, there are AA and NA. Some concerned employers (and wives) require proof of regular attendance. The Mission has a rehabilitation unit out in the country which can usually take anyone who is serious about sobering—and straightening—up. There was detox and alcoholic commitment—which helped more than is usually realized. And there is Antabuse.

We are now left with the remaining unfortunate street people—the homeless and the hungry who, through clearsighted energetic policy, may be helped to better their condition. I was never asked to do anything I did not want on the streets. Of all the places I ate, I was never asked to bow my head; only once was I asked to take off my cap. I was not expected to clean up my mess—indeed, volunteers, prime examples of self-discipline and responsibility, are recruited from the community to do the dirty work. In the food line at the Sally I once intentionally smashed styrofoam cups and threw the pieces on the street as a kindly looking old gentleman stooped over with a Tufly bag picking up the trash left by the men. He saw me, saw what I was doing, bent over, picked up the pieces, put them in his plastic bag, half rose, looked up at me and smiled. Then he went on down the line.

Policymakers and planners took sociology and psychology in college. Many of them are specialists with advanced degrees in the social sciences. You would never know it by comparing their proclaimed goals with their arrangements and implementation of their programs. It appears that the 22 recommendations listed as part of the request for the $3.9 million for aid to the homeless in Tennessee will have negligible impact on those already on the street and will, if past evidence of similar programs is indicative of the future, only increase the numbers able to survive on the streets. The major result will be to enlarge the bureaucracy caring for Streetniks and to institutionalize the present patterns.

We are well on the way to creating an enduring underclass in America for the first time in our history. Both the lower class and the larger society have in the past shared the same goals and values, generally speaking, even though the lower class was increasingly allowed to give them lip service only. An underclass of three million homeless, with values in opposition to the larger society, can create major problems for communities, since it is impossible both to remove and to accept.

There is a compassion that ennobles and motivates. Members of Alcoholics Anonymous call this “tough love.” And then there is a compassion that smothers and stifles. In my opinion, based on my investigations and my observations and my readings, the current policy we are applying to the homeless at great expense—producing much misery and violence to boot—is smothering compassion. Mercifully, however, someone’s report on this subject did end with this observation: “Sometimes the absolute worst thing we can do for the truly needy is to amply aid those who are obviously not.”

Leave a Reply