She’s just won the Grammy for album of the year. Her boyfriend is on his way to the Super Bowl. Will Taylor Swift end 2024 as triumphantly as she began it—by tipping the presidential election?

Fans surge to register whenever Swift promotes voting, and she endorsed Joe Biden last time. But it’s a fair bet most Swifties who care about elections are already on the rolls and included in polling; they’re not a swing constituency. And while new registrations matter, every presidential election produces plenty of those.

It’s more likely that Swift hastens registrations among Zoomer women who would sooner or later participate anyway—driven by support for abortion or loathing of Donald Trump—than that she conjures a new demographic from apolitical music lovers.

Swift’s politics are simply too ordinary to make her a force for change. Her views are fine-tuned to fit what her listeners (and peers in the entertainment industry) already believe. What’s true of her music applies to her opinions; this is safe, mainstream stuff for the masses, or rather, since the masses and political consensus are a thing of the past, this is what a large but limited market wants.

Swift’s support for LGBTQ causes and service-sector labor unions and carbon offsets to combat climate change make her a safely conventional 21st-century liberal. Indeed, it’s easier to profess these views than it would be to say nothing, since silence about gender or climate, like color-blindness in racial politics, is now deemed an actively right-wing stance by progressives.

In 2012, Swift told Time, “I don’t talk about politics because it might influence other people. And I don’t think that I know enough yet in life to be telling people who to vote for.” She’s older now—but is she politically wiser, or just wise to the risk of remaining neutral when her industry and audience profile demand taking a side?

Left-of-center social and economic attitudes are, for Millennial and Generation Z women, the closest thing to not having any politics: They are the path of least resistance—and least reflection.

Significantly, Swift’s political passions stop at the water’s edge: She’s made no forays into Israel-Palestine issues, which have the potential to embroil her in real conflict with some of her audience and admirers.

As a celebrity in 21st-century America, Swift is second only to Trump, if that. Yet she’s politically inert—though in many respects she’s Trump’s opposite number.

Trump’s base skews male, and his support among women is strongest with married women. Male Swifties aren’t unheard of, but Swift’s lyrics about failed relationships with men are the bedrock of her appeal to a mostly female fanbase. She’s the most famous woman in America today because, perhaps uniquely, she combines antithetical dreams and aspirations.

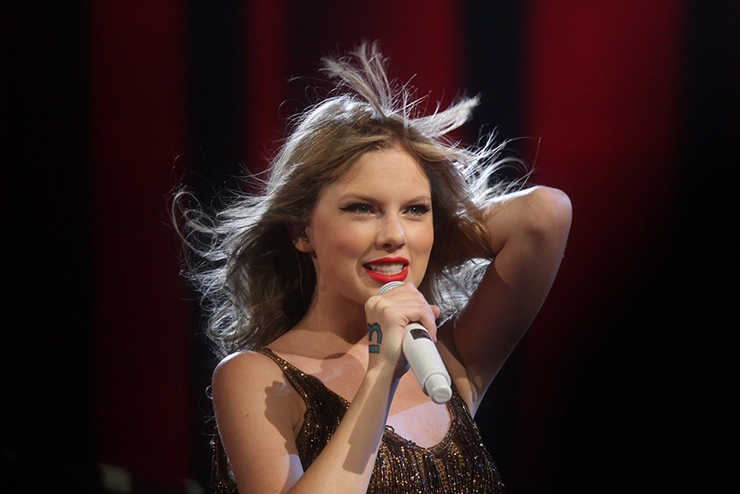

Swift is blue-eyed, blonde, beautiful, classically feminine in an age when beauty is supposed to encompass the widest array of body types and what it means to be a woman is open to question. She’s Miss Americana—the homecoming queen dating the football hero who’s headed to the championship. And although she’s sexy, she hasn’t sold herself as a sex object the way a Madonna or Cardi B has.

Swift represents quite a traditional image of happiness for a young American woman. But she also represents a later feminist ideal—her songs are scathing about men, and she’s richer than her boyfriend. She’s independent—yet still adheres to a midcentury archetype: feminist and feminine.

That’s a powerful formula, neither so restrictive that it repels teenage girls who want the freedom to define themselves nor so open-ended it leaves them lost in a maze of revisionist identities.

Men who like Trump don’t necessarily want to be him—especially if they’re conservative Christians—but they think the forces against him, or that he’s against, are the same ones against them: political correctness, globalization, a credentialist elite. Those forces are against masculinity, too, as PC demands sensitivity, the economy turns labor unisex, and education favors conscientious girls and women over individualistic (for better or worse) boys and men.

The discontents of Trump’s male voters lend themselves to a political style, if not always an articulate program, and translate into a potent electoral force. The Swift phenomenon has roots just as deep and equally entangled with sex and identity—but it’s based on a fragile contentment, not politically galvanizing discontent.

What happens when the two halves of Swiftism, feminist and feminine, are pulled apart by progressives’ attacks on the meaning of men and women? Across the developed world, women are moving left while men are going right.

But it’s hard to see a place for the well-defined femininity of Taylor Swift in the future progressives are building. For now, the Swifties lean left; tomorrow, when the consequences of progressive politics sink in, they may come to a new appreciation for the right.

COPYRIGHT 2024 CREATORS.COM

Leave a Reply