Throughout our legal history we are familiar with incidents of jury-tampering, the act of buying off or frightening one or more of the 12 men good and true called upon to decide a case. This is done to predetermine a verdict, usually to assure a “not guilty.” We have heard of vicious gangsters, corrupt union bosses, and crooked politicians conspiring to rig juries. But who has ever heard of a jury rigging itself? Recently I served on one attempting to do just that. Not for money nor from blackmail. More subtle pressures obtained, psychological pressures, emotional pressures, moral pressures.

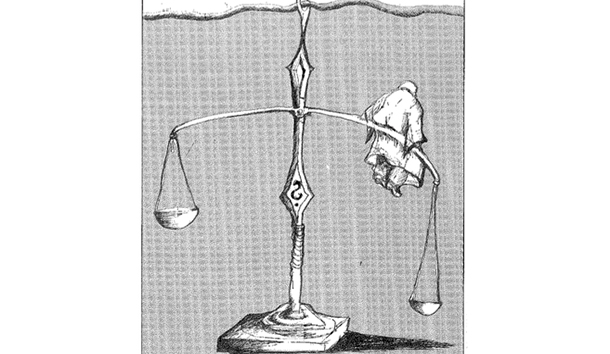

The question of jury psychology has long attracted attention (recall the film Twelve Angry Men), but never more than today, when we have famous cases involving the likes of Rodney King, Reginald Denny, the Menendez brothers, and John and Lorena Bobbitt. Court TV is there to bring them to us live and uncensored. Mesmerized, we watch the acquittals roll in: Not Guilty, Not Guilty, Hung Jury, Not Guilty by reason of temporary insanity—take six weeks in a clinic. And we sit bewildered, as the latest crime statistics are published. Yes, they are skyrocketing, but not to worry: the citizenry is astir and congressmen are introducing federal legislation. This month’s crime bill will pass and become law. And so there will be even more cases for juries to decide. How will they decide them?

How should they decide them? Will anything change? George P. Fletcher, law professor at Columbia University, writes that the only check on wayward juries is for “our judges to be more vigilant against speculative lines of attack that play on jurors’ fears with buzz words like child abuse and racism. They must rein in defense lawyers who have wakened to the potential of putting the victim on trial.”

Fletcher is probably right, but it is delusive to think judges are going to strip lawyers of a powerful weapon. Attorneys will continue to incite jurors’ fears, for there is a fortune in gold to be mined from that lode. Fear. It was a palpable presence in the jury room where I sat, a 13th juror. It infected nearly everyone. The squalid little case I will recount is a useful lens for viewing the celebrated, protracted, nationally known media events, because, in a run-of-the-mill trial with a nonentity of a defendant, a verdict that should have been reached in 15 minutes instead took four anguished days to reach.

The venue for this case was the city of Paterson in Passaic County, New Jersey. Anyone familiar with the area will immediately know from where the jury was culled: suburban towns like Little Falls, Clifton, West Paterson, and Wayne. Strolling through the courthouse common room and its environs where the various jury panels await their summons to the courtroom, I was struck by the sea of white faces: people queued up at the snack bar, some slouched in hard plastic chairs scanning newspapers and magazines, others watched the big television and sipped coffee from cardboard cups, still others made calls at pay phones. All wore the round “Passaic County Juror” buttons pinned sheepishly to their chests and stood out, in this heavily black and Hispanic town, from the clerical staff of the courthouse and municipal building, who are also mostly black and Hispanic.

The jurors had never met before, but they knew each other well enough. They are, after all, neighbors, working middleclass folk. They earn from 20 to 60 thousand dollars a year and range in age from 21 to 65. They dress in a similar neat suburban fashion, slacks, open-collared sport shirts, sweaters, skirts, dresses. They dine in many of the same restaurants, frequent many of the same movie theaters, vote in many of the same schoolhouses. They converse while they wait. They discuss their jobs, their families, their bad luck in being called here. For many it was their first jury assignment. The county sheriff had already given them a pep talk and shown them a 30-minute film about the glories of jury duty designed to stoke their civic consciences. They were bored and unimpressed by it and relieved when it ended. They wondered what type of cases they would draw. They discussed the jury system in general and an underlying theme emerged: a fervent hope that they would not be called upon to decide anything of consequence. Should this occur, however, many prepared excuses for the judge in order to be thrown off the case. Prejudice, toward the plaintiff, the defendant, or both, was the favorite. Soon a uniformed officer of the court appeared and instructed four panels to report to the courtroom. Quickly they gathered themselves and were led out in double rows and disappeared down the hallway.

Up in the courtroom we fidgeted in our seats in the jury box and answered questions by the attorneys prior to their challenges. We took note of the defendant, a young Hispanic male in jacket and tie sitting with folded hands and glowering at us menacingly, and of the reporters from the local paper wearing press badges. We were warned by the bench not to speak with them nor read any accounts of the case while it was ongoing.

Once the jury was finalized we heard the charges. There were four: attempted murder, aggravated assault, resisting arrest, willful and malicious destruction of property. On a summer’s night six months back, we were told by the prosecutor, a paunchy, disheveled man, the enraged defendant, a Cuban immigrant who had come here when Fidel Castro emptied his jails, had burst into his ex-girlfriend’s apartment and attempted to kill her with a semiautomatic pistol. Five wild rounds were fired before he made off in a vehicle. The police were called and a high-speed chase ensued. When the cops apprehended him he threatened them with the pistol, which was wrested from him, then sought to flee on foot, whereupon he was pursued again, caught, and taken into custody.

The key witness against him, the plaintiff, was the ex-girlfriend, a young black woman. Called to testify by the prosecutor, she recounted the events of that night. Asked why he would want to kill her, she defined it as retaliatory. She stated that she had at one time lived with the defendant but after a brief period had put him out of her apartment because of threats and physical beatings. She went on to describe his abuse in brutal detail. Secondary witnesses were then called to describe events and corroborate the girl’s story. All the testimony was straightforward and hung together.

Then came the defense. The girl resumed the stand. The public defender, a big well-built man in his 30’s, elegantly attired and beautifully articulate, went to work on her with gusto and flair. He was clearly looking to go places, and Passaic County was not one of them. He sauntered over and leaned rakishly against the railing of the jury box as he delivered his questions, so close to us that we could smell his cologne.

“Miss Smith,” he said to her, “please tell the jury how you met the defendant.”

“I was sittin’ in my car one day on the street and he come up to me and started to talk,” she said.

“What did he say?”

“He said I have a good body and he want to know me.”

“How soon after that did you commence living with him?”

The girl hesitated. “That night.”

The attorney paused to let this sink in. Then he said, “It is my understanding that you have a two-year-old child by another man. Did this child live with you and the defendant?”

“Well,” she said, “For a couple days it did. Then I gave the baby to my mother to keep.”

The lawyer scowled. “Let me understand this,” he said, looking at us. “You had a two-year-old baby that you suddenly abandoned to your mother so you could live freely with a man you had met two days earlier on the street. Is that correct?”

“Yes.”

Looking at each of us in turn, he shook his head. I glanced at the other jurors for a reaction. All but one, whose head was down with eyes closed, softly snoring, were riveted.

The cross-examination wound down. Defense got her to admit practicing rough sex, then to withholding sex when the boyfriend did not work and bring home a paycheck. Then, said defense, she threw him out on the street. His frustrations mounted when she refused to see him to discuss reconciliation. She was his common-law wife and most couples are prone to domestic quarrels, and really, was she not overreacting by pressing grave charges that could send a man to prison for a long while? Or was she trying to wreak vengeance via the court?

Seeing trouble staring him in the face with 24 eyes, the prosecutor frantically did his best during summation to counter the defense by recapitulating the facts, battered doors and bullet holes in the molding, and lectured us on our duty to convict. The defense, perfectly assessing the jury’s mindset, focused on reasonable doubt and Miss Smith’s dubious character, linking the two. Despite the fact the defendant was no angel, he said, we must acquit. After one full day of testimony, we returned the following morning to begin deliberations.

From the moment we entered, there was tension in the jury room. At first, little cliques of two or three people formed, joking about the testimony and giggling nervously. Someone called us to order and we introduced ourselves and elected a foreman, a woman named Sheila. All white, we were composed equally of men and women. Then a poll was taken. The results were startling: ten votes for acquittal on all charges. There was really very little to deliberate about, the ten agreed, nodding sagely. Voting for conviction, only me and one other.

Right then the revolt began. And as with all revolts, a leader spontaneously arose, a man named Don. Tall, thin, fortyish, shaggy-haired and bespectacled, he looked like a reference librarian. In fact, he was a CPA with a wife and two children. Compared with Don, the rock of Gibraltar is made of papiermâché, as the room discovered to its dismay. Outraged by their attempt to preclude discussion, he removed his glasses and tore into them like a tiger.

“What kind of setup is this?” he fumed. “If I didn’t know better I’d swear the fix was in. And you,” he said scathingly to the juror who had dozed during the trial, “how dare you even talk when you slept through the testimony! That defendant is an animal, guilty as sin. And you all know it.” He slammed his fist against the table as the whole room boiled and seethed.

But they fairly tripped over one another in their rush to justify themselves. As I listened it began to dawn on me. These were decent people desperate to escape, and to escape quickly and cheaply. They were reciting almost verbatim the ridiculous legal formulation tossed out by the defense—reasonable doubt—to argue that since no one could know what had transpired between the principals, reasonable doubt existed over the veracity of the girl’s account, ergo, the defendant must go free. As to the shooting, well, he might have passed the breaking point. And if the police were chasing, it was natural in Paterson for a Hispanic male to run! And since all the issues were so murky, since reasonable doubt existed down the line, we had no choice but to acquit.

This, then, was the smoke screen, their intellectual underpinning, such as it was. Over the course of four days, as Don and I harangued, harassed, entreated, reasoned with, coaxed, cajoled, scolded, and shamed them, the truth broke through in bits and pieces. It was not evidence but fear and guilt that drove them, and, in an ironic twist, proved a contention of theirs that people are victims of their environment. For those ten jurors were victims of the permissive social environment of the last 30 years, morally disarmed before criminals, naked unto their enemies.

Their visceral beliefs and true reasoning, from their own statements, consisted of the following:

One, fear for their physical safety. “Didn’t you see the way he [the defendant] looked at us? He knows who we are. If we convict him, he’ll come back and get us later.” Sheila, Mary, Nadine.

Two, moral relativity of truth. “We have no right to judge [?!]. We were not privy to their lives. What’s true for us might not be true for them. Besides, the truth ultimately can’t be known. Maybe she [the plaintiff] had it coming. And she did abandon her child.” Mary, Nadine, Frank.

Three, outright moral cowardice. “The responsibility for putting someone away is too heavy and I don’t want it on my conscience. We didn’t ask to be here.” Bill, Henry, Nancy.

Four, racism and white guilt. “Those people live completely differently from us and shouldn’t be held to our standards. They’re always mistreated and victimized by society.” Mary, Nadine, Tom.

Five, lack of moral imagination, denial. “Even though we hear about it all the time, I can’t believe someone would commit such violent acts without some justification. There are extenuating circumstances.” Keith, Nadine, Mary, Bill, Nancy.

Six, fear of exercising power, misplaced conscience, spinelessness. “I hate to think of myself as an enforcer for the state. Anyway, in the grand scheme of things it really doesn’t matter what we do. Crime will be the same whether we convict or acquit.” Fred, Denise.

And so there it was. The excuses interlocked and reinforced one another. Back and forth we went, hour by grueling hour, day by weary day. The bailiff came in every few hours to try to hurry us up. The judge had expected a fast decision and was angry we were taking so long. Throughout, Don was magnificent. He spoke more eloquently than any film of civic duty and courage, of the need to stop the barbarians at the gate, of personal responsibility, of recognizing necessity, of the right of the victim to justice. One by one they attacked him with their craven arguments, only to wind up impaled on the sharp spear of his logic. Gradually, imperceptibly at first, we began to turn them. From ten to two it became eight to four by the end of the second day, 16 hours in. Then it was tied. Near the end of the third day, eight to four in our favor. By midday Friday we had it: 12 out of 12 for conviction. Whether by force of argument or sheer exhaustion, we had it. We notified the judge, and he sent word that the defense attorney intended to poll the jury in open court. For certain that fox hoped to pry loose a juror or two and get a mistrial should the verdict be against him. It was a smart tactic that almost worked. A crisis erupted in the jury room. It was one thing for them to convict anonymously, but quite another to stand individually before God and everyone and speak their vote aloud.

They tottered on the brink of declaring a hung jury. But Don steeled them for the final leap in typical fashion. “The hell with the lawyer. Look him straight in the eye when you speak. You can be certain you’ve done the right thing. I know it, and I want you to know it.”

Back in the jury box, 12 men and women rose and confirmed the verdict one by one, “Guilty on all charges.” The judge dismissed us. Sentence would be pronounced a month later, and what it was I never learned. At the courtroom exit Don and I stopped and stood together for a moment after everyone had filed out. We did not exchange a word. We looked hard at each other, though, perhaps for memory’s sake, shook our heads, grinned, and clasped hands, then went our separate ways.

Since then I have often wondered if the outcome would have been different had Don not sat on that particular jury. Was the Menendez jury like ours? Was Reginald Denny’s? Clearly it is difficult in our society to distinguish evil, to call it by its true name, punish it as justly as our wisdom allows, and deter it in the future. Our faculty for ethical decision-making has been warped by moral relativism, psychologism, and alternative lifestyles. There are no longer two sides to every story but 50, all of equal value. Evil deeds are explained away with pseudoscientific, legalistic, psychosocial mumbojumbo. The jurors in our case were victims of this, their minds rigged in advance, chanting formulas of fear like incantations. Perhaps this is a defense mechanism, a reflexive recoiling from daily horrors. But in doing so we are colluding with the thugs in our midst by rationalizing their crimes and depredations.

The time is long past for us to quit quaking and to accept responsibility for judging and acting upon what is right and just, whether at school, in the street, or in the jury box. We must make choices not to our liking. As J.R.R. Tolkien asks in The Lord of the Rings, “How shall a man judge what to do in such times?” “As he ever had judged,” said Aragorn. “Good and ill have not changed since yesteryear; nor are they one thing among Elves and Dwarves and another among men. It is a man’s part to discern them.”

Just so.

Leave a Reply