Twelve-year-old North Carolinian Mike Wimmer recently graduated as valedictorian of his high school class while simultaneously earning an associate’s degree at his local community college. Cooped up like everyone else during the pandemic, young Wimmer decided to go to a full court academic press and add some classes to his schedule. “Well we’re sitting here doing nothing, right? So might as well take a few extra classes and get some stuff knocked out.”

The kid knocked it out of the ballpark.

This youngster has also started two technology companies. In case you’re thinking he’s only into academics, however, he reports his room is filled with Hot Wheels cars, racetracks, and Legos. “I’m having the time of my life doing everything,” he said, “whether that is school and my businesses and still being a kid as well.”

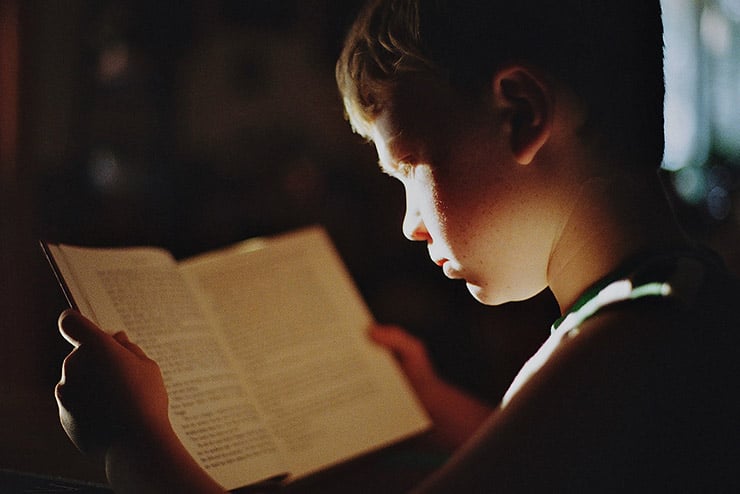

Wimmer’s story sends a clear message: We need to demand more of our young people.

Some parents recognize this principle and are putting it into practice with their own children. One of these parents is Marion Scott. On the day I read this piece about Mike Wimmer, I was going over some notes I’d taken while interviewing Scott and his wife, Rosa, homeschooling parents who also happen to be concert pianists and teachers—you can find their impressive list of credentials here. Not surprisingly, their two young daughters play competitively as well.

For their daughters’ schooling, they use the Seton Home Study School, a rigorous full-curriculum program. “I believe kids can handle more than some of us think,” Marion says. “I’m glad we have a demanding academic curriculum. Some of my colleagues from places like Russia and China are shocked by how few demands we make of our children.”

This stands in stark contrast to the demands many of our public and private schools place (or don’t place) on students, a fact Dennis Prager recently noted. He blasts these schools both for their political agendas and for their failure to teach students fundamentals, challenging us to ask young college students the following questions to see what they’ve learned in all their years in school.

Ask your college son or daughter to diagram a sentence; identify Joseph Stalin, ‘The Gulag Archipelago’ or the Soviet Union; name the branches of the American government; identify — or just spell — Ludwig van Beethoven; date the Civil War; identify the Holocaust; and name which sentence is correct — ‘He gave the book to my friend and me’ or, ‘He gave the book to my friend and I.’

Pretty basic stuff, yes?

Except for the diagramming, which few schools teach anymore, students should have learned the answers to the rest of these questions by high school graduation at the latest. If they can’t answer them when in college, these students are cultural illiterates, and their children may be the same.

I should note that some teachers and coaches, although often hampered by administrators, understand that the young have untapped reserves of energy and ability. During the fall of my senior year in high school, for example, I left the cross-country team and played football as a defensive back. Our coach was Mr. Harper, a short, scrawny man who was as tough as they come. During the pre-season, we drilled twice a day in the Carolina heat, running play patterns countless times and tackling and blocking each other without mercy. All the while Coach Harper screamed at us—or at least that’s how he appears in my memory 50 years later, the veins in his neck sticking out, head forward, always egging us on to strive for excellence.

Right now we need adults like Mr. Harper as role models for our teachers and parents. We need men and women who will challenge young people to excel, who will push them—shove them if necessary—to fulfill their talents.

The kids are up to challenges. Some years ago, I was a teacher for homeschooled students. In the classes I offered in composition and literature for middle-schoolers, I required students to write a 1,500-word essay in which they mapped out their future for the next 15 years. We took about a month on this paper, writing and editing it part by part, and though some of them moaned and groaned the entire time, most of the students turned in a decent paper at the end of the term.

Now a caveat about my thoughts here: Students with the intellectual capabilities, drive, and positive parental support of a Mike Wimmer are rare. We should applaud him for his accomplishments, but we should also recognize that we often stress academic accomplishments at the expense of other talents possessed by the young. Our primary goal is not to produce intellectuals, but confident, knowledgeable adults ready to tackle the future. One of my students, for instance, later became a welder, another bright young woman decided to become a hairdresser rather than go to university, and one, a mediocre student named Madison Cawthorn, never graduated from college but today is the youngest member of Congress.

Our kids were made to fulfill their potential, not for mediocrity. Let’s help them get there.

Image Credit:

Pixabay

Leave a Reply