In the course of American history, nationalism and republicanism have usually been enemies, not allies. From the days of Alexander Hamilton, nationalism has meant unification of the country under a centralized government, the supremacy of the executive over the legislative branch, the reduction of states’ rights and local and sectional parochialism, governmental regulation of the economy and engineering of social institutions, and an activist foreign policy—expansionist, imperialist, or globalist—that costs much money and requires at least occasional wars. Nationalism and its proponents have historically been Anglophiles, emulating the mercantilist dynastic state that flourished in Great Britain from the 18th century, and for all their claims of overcoming sectionalism and private interests, they have been identified with the Northeastern parts of the United States and its institutions—New England, New York City, the Ivy League, Big Banks and Big Business, Wall Street, and Washington. The national state the nationalists defended and constructed was born with the ratification of the U.S. Constitution, reached adolescence in the victory of the North in the Civil War, and grew to a corpulent adulthood in the 20th-century managerial state of Woodrow Wilson, Herbert Hoover, Franklin Roosevelt, and Lyndon Johnson.

The principal opponents of nationalism in American history have been republicans, and it is one of the ironies of our history that the political party that claims the republican name has been the chief vehicle since the Civil War of anti-republican nationalism. The Antifederalists who opposed ratification of the Constitution were men immersed in the political theory of classical republicanism, a school of thought that originated in modern times with Machiavelli, found expression in 17th century British resistance to the powers of the monarchy, and in the 18th century influenced both radical Tories and radical Whigs. Deeply suspicious of centralized power of any kind and of the corruption it bred, the Antifederalists opposed ratification, demanded a Bill of Rights to limit federal power, insisted on a strict reading of the constitutional text as the basis of law, defended the states against the federal government and the Congress against the Presidency, and were generally content with the limitations on wealth and national power that a small, restricted state imposed, in preference to what they condemned as the “luxury” and “empire” that national consolidation and an interventionist foreign policy would encourage. “The anti-federalists,” writes Professor Ralph Ketcham in his introduction to a popular edition of their writings,

looked to the Classical idealization of the small, pastoral republic where virtuous, self-reliant citizens managed their own affairs and shunned the power and glory of empire. To them, the victory in the American Revolution meant not so much the big chance to become a wealthy world power, but rather the opportunity to achieve a genuinely republican polity, far from the greed, lust for power, and tyranny that had generally characterized human society.

Though the Antifederalists lost, their ideas, far more than those of Edmund Burke and Adam Smith, have informed the long American tradition of resistance to the leviathan state of the nationalists, appearing in the thought and on the lips of John Randolph, John C. Calhoun, the leaders of the Confederacy, the Populists of the late 19th century and the Southern Agrarians of the early 20th, and in the Old Right conservatism of the era between Charles Lindbergh and Jesse Helms.

In the 18th century, when the debate between these two sides of the American political coin still sparkled, it was possible for the American people and their leaders to choose republicanism and to institutionalize its ideals. Perhaps it was possible to do so as late as the early 20th century, before the managerial state began to crystallize. Today it is no longer possible. The national state has long since triumphed, and with it, wedded to it like Siamese siblings, multinational corporations, giant labor unions, universities and foundations, and all the titanic labyrinth of modern bureaucratic organizations in both the “public” and the increasingly illusory “private” sectors have won as well. To establish republicanism in anything like its classical form would involve a massive rejection and dismantlement of the main features of the 20th century—the physical and social technologies by which modern, centralized, bureaucratically managed mass organizations operate—and while the continued existence and dominance of such features are not inevitable in any Hegelian sense, no one save a few romantic reactionaries seriously contemplates doing away with them. Not only do technology and its organizational applications entice us with “luxury”—what we today complacently call a “high standard of living”—but also they offer to those who understand how to manipulate them a degree of power unknown to the most imperious despots of the past. The elites that manage modern mass organizations and master the technical skills that allow these organizations to function cannot permit the decentralization and autonomy that characterize republican civic culture simply because their own power would vanish, and these elites are lodged not only in the.state but also in the dominant organizations of the economy and culture so that our incomes and our very thoughts, values, tastes, and emotions are conditioned and manipulated by them and their apologists. Short of a new Dark Age (or perhaps it would be a Golden Age), in which knowledge of scientific and organizational technology is lost, there is no prospect of reversing the trend toward mass organization and its absorption of local and decentralized institutions.

Moreover, as most students of classical republicanism understand, the distinctive principle of its theory is its concept of “virtue,” a quality that consists less in moralistic purity than in personal and social independence. Owning and operating his own farm or shop, usually producing his own food and clothing, governing his own family and his own community, and defending himself with his own arms in company with his own relatives and neighbors, the citizen of the classical republic neither needed nor wanted a leviathan state to fight wars across the globe in behalf of democracy nor to pretend to protect him and his home. Nor did he need or want a job in someone else’s company, or a pension plan or health benefits or paid vacations or five-hour workdays. He did not want to shop in vast shopping malls where nothing is worth buying and nothing bought will last the year. It did not occur to him to enroll himself or his children in therapy courses or in sensitivity and human-relations clinics in order to find out how to get along with his neighbors, and he sought no edification or instruction from the mass media to entertain him continuously or indoctrinate him with the current cliches and slogans of public discussion or trick him into buying even more junk for which he had no use and no desire, if the citizen succumbed to such temptations, then he had become dependent on someone or something other than himself and his extensions in family and community. Men who become dependent on others cannot govern themselves, and if they cannot govern themselves, they cannot keep a republic.

Today, virtually everyone in the United States is habituated to a style of living that is wrapped up in dependency on mass organizations of one kind or another—supermarkets, hospitals, insurance companies, the bureaucratized police, local government, the mass media, the factories and office buildings where we work, the apartment complexes and suburban communities where we live, and the massive, remote, and mysterious national state that supervises almost every detail of our lives. Most Americans cannot even imagine life without such dependencies and would not want to live without them if they could imagine it. The classical republicans were right. Having become dependent on others for our livelihoods, our protection, our entertainment, and even our thoughts and tastes, we are corrupted. We neither want a republic nor could we keep it if we had one. We do not deserve to have one, and like the barbarians conquered and. enslaved by the Greeks and Romans, we are suited only for servitude.

Classical republicanism, then, is defunct as a serious political alternative to the present regime, but this does not mean that Americans should either embrace the old, Hamiltonian nationalism or merely squat passively in their kennels waiting for the next whistle from their masters. Even though virtually no one today subscribes or adheres to the classical republican ideal of virtue and independence, even though most Americans are too “corrupt” (in republican terms) to support a republic, there remain a large number of Americans, perhaps a majority, whose material interests and most deeply held cultural codes are endangered by the national (and increasingly supranational) managerial regime. These “Middle Americans,” largely white and middle class, derive their income from their dependence on the mass structures of the managerial economy, and, because many of them have long since lost their habits of self-reliance, they also are dependent on the services of the government (at least indirectly) and the dominant culture. Yet despite their dependency, the regime does little for them and much to them. They find that their jobs are insecure, their savings stripped of value, their neighborhoods and schools and homes unsafe, their elected leaders indifferent and often crooked, their moral beliefs and religious professions and social codes under perpetual attack even from their own government, their children taught to despise what they believe, their very identity and heritage as a people threatened, and their future—political, economic, cultural, racial, national, and personal—uncertain. They find that no matter which party or candidate they support, no matter what the candidates and parties promise, nothing substantially changes, except for the worse. Although they • do the labor that sustains the managerial system, pay the taxes that support it, fight the wars its leaders devise, raise the families and try to pass on the beliefs and habits that enable the regime and the country to exist and survive, what they receive from the regime is never commensurate with what they give it.

They are the Americans sneered at as the “Bubba vote,” mocked as Archie Bunkers, and denounced as the racists, sexists, anti-Semites, xenophobes, homophobes, and hate criminals who haunt the dark corners of the land, the “Dark Side” of. America, even as their own energy, sacrifice, and commitment make possible the regime and the elite that despise them, exploit them, and dispossess them. They are at once the real victims of the regime and the core or nucleus of American civilization, the Real America, the American Nation.

Throughout this century, Middle Americans have gradually acquired a collective consciousness, an awareness of who they are and what their position is in the regime that exploits them. In economically prosperous periods, the radicalism of that consciousness is largely dormant, but in the Depression, the inflationary crunch of the 1970’s, and the recessions of the early 1980’s and the early 1990’s, material insecurity has served as a trigger for a heightened consciousness, a radicalization, a sharper self-perception of their plight. Neither liberalism and the ideologies of the left nor mainstream conservatism, an entrepreneurial version of classical republicanism, adequately expresses their plight or their interests and values or offers much of a solution.

The left offers nothing but economic redistribution predicated on egalitarian and universalist dogmas, and in practice this means that liberal-left policies reflect the interests of the nonwhite underclass and the intelligentsia that designs the formulas and policies of the left. Hence, the left is incapable of defending the specific interests and concrete cultural norms of Middle Americans. The right, though it defends (in theory) Middle-American cultural norms and institutions, offers a vision of decentralism, strict constitutionalism, economic individualism, and a minimal state that fails to speak to Middle-American material interests and the challenges that they typically encounter. What Middle Americans need is a political formula and a public myth that synthesize the attention to material-economic interests offered by the left with the defense of concrete cultural and national identity offered by the right. The division of the American political spectrum into the categories of right and left makes the political expression of such a formula virtually impossible.

The appropriate formula for the expression of Middle-American material interests and cultural values is nationalism. The managerial state and its linked economic and cultural structures have succeeded in breaking down the regional variations, local and sectional autonomy, and institutional stability and independence of Middle Americans, and the regime now lurches happily toward a globalization that seeks to integrate all Americans (and all other peoples as well) into a planetary political, economic, demographic, and cultural order in which national identity will eventually disappear entirely. The homogenization of subnational social and regional differences through political centralization, urbanization and mobility, mass communications, and mass consumption and production means that the older, decentralized identities of particular social classes, sections, communities, and religious and ethnic groups no longer effectively mobilize Americans for political action. Identities as Southerners or Midwesterners, Catholic or Protestant, Anglo-Saxon Old Stock or European ethnic, small businessman or assembly-line worker, no longer seem to offer sufficient bonds or common interests for serious political cooperation for any goal beyond immediate special interests. The emerging identity, of Middle America, however, appears to convey sufficient meaning to serve as the foundation of a politically and socially important force, and a nationalism that is politically and culturally based on Middle Americans, expresses their material interests, and affirms their cultural norms as the dominant public myth of American civilization is today the only possible vehicle for effective resistance to managerial globalism and the national and cultural extinction it threatens.

Moreover, only nationalism seems capable of organizing offensively on a collective scale. One reason for the failure of classical republicanism and similar decentralist movements was that they were capable of only defensive maneuvering and were never able to overcome divisions of particular and divergent interests and identities sufficiently to organize an effective offensive strategy aimed at dominance rather than mere survival and liberty. The defensive strategy mounted by the Confederacy during the Civil War was one of the main reasons for its military defeat, and similar defensiveness has crippled conservative tactics as well. Activated only by immediate threats to local or private interests, conservative forces have organized mainly around striking personalities and “single issues”—tax revolts, religious and social issues of largely sectarian concern, antibusing and educational movements, anticommunism, deregulation, term limits—and they tend to disband or wither when their favorite personality is elected or the threats to their immediate interests and pet causes seem to be pushed back. Nationalism, through its historically proven capacity to mobilize passions of mass solidarity and sacrifice and its aggressive invocation of collective identity, offers a practical instrument for overcoming the burden of a purely defensive conservatism and aspiring to enduring cultural and political power.

The old nationalism of the Hamiltonian tradition will not suffice for this purpose, however. It was the explicit mission of Hamiltonian nationalism to obliterate what Hamilton’s best and most recent biographer, Forrest McDonald, calls “the inertia of a social order whose pervasive attributes were provincialism and lassitude.” The means by which Hamilton determined to accomplish that “revolutionary change” was money—wealth, economic growth—aided and supported by the national state. “To transform the established order,” writes Professor McDonald,

to make society fluid and open to merit, to make industry both rewarding and necessary, all that needed to be done was to monetize the whole—to rig the rules of the game so that money would become the universal measure of the value of things. For money is oblivious to class, status, color, and inherited social position; money is the ultimate, neutral, impersonal arbiter. Infused into an oligarchical, agrarian social order, money would be the leaven, the fermenting yeast, that would stimulate growth, change, prosperity, and national strength.

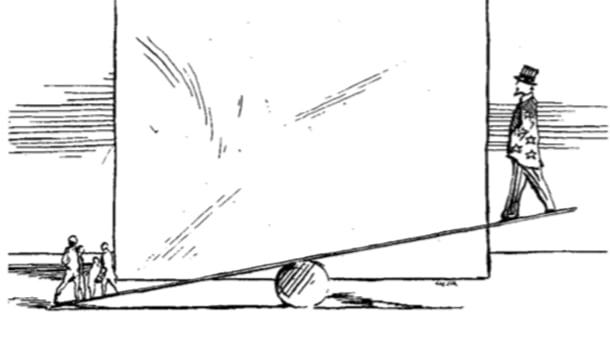

But by making money “the universal measure of the value of things,” the defining principle of the national identity, and joining it to centralized power, Hamilton ultimately defeated his own purposes. In the first place, because his nationalism set itself against existing social institutions and habits, it was necessarily alienated from and adversarial toward the norms by which most Americans lived, and its alienation has persisted for two centuries to inform the cultural style and attitudes of the dominant elites of the managerial system toward the rest of the country. Secondly, because his nationalism was based on the abstraction of money, it was unable to win the support of any but economically ambitious Americans and unable to express or sustain a genuinely national or even any genuine social bond. Hence, Hamilton’s nationalism—rational, calculative, pragmatic—degenerated into a mask for individual, factional, and sectional acquisition. It was not and could not be an authentic nationalism that controlled and disciplined the parts within the whole but only a pseudo-nationalism that allowed the parts to seize control of the whole and define the whole in terms of the parts and their interests. As another of Hamilton’s biographers, John C. Miller, writes, the failure of Hamilton’s nationalism probably “stemmed from the fact that he associated the national government with no great moral issue capable of capturing the popular imagination; he seemed to stand only for ‘the natural right of the great fishes to eat up the little ones whenever they can catch them.'”

American nationalism after Hamilton, especially through Abraham Lincoln, sought to rectify this flaw by defining the ideal of national unity in terms of (more accurately, masking it with) a “great moral issue.” Manifest Destiny was one such issue, and it quickly became a mask for territorial expansion, surviving in Wilsonian internationalism, the messianic anticommunism of Cold War liberalism, and the global democratism and “New World Order” of the post-Cold War neoconservatives. Equality was another such issue, and it too served as a mask for acquisitive individualism. Harry Jaffa is in a sense correct that the “principle of Equality” as he perceives it in the Declaration of Independence and in Lincoln’s thought “is the ground for the recognition of those human differences which arise naturally, but in civil society when human industry and acquisitiveness are emancipated,” though he is wrong in claiming that equality is “far from enfranchising any leveling action of government.” The very process by which human acquisitiveness is “emancipated” involves the obliteration by the state of social barriers to acquisitiveness, and so it did in the attack on property and federalism that Lincoln unleashed in the Civil War. Hence, M.E. Bradford is also (and more importantly) correct when he writes that the depredations and corruptions of the Gilded Age, the “era of the Great Barbecue,” the original “vulture capitalism,” “began either under [Lincoln’s] direction or with his sponsorship” and that Lincoln’s administration laid “the cornerstone of this great alteration in the posture of the Federal government toward the sponsorship of business.” It was indeed the cornerstone of the modem corporate state on which the twin towers of managerial capitalism and managerial government are grounded. The “great moral issues” that the old nationalism eventually selected, therefore, were little more than fantastic and easily penetrated costumes in which even older human passions of greed and lust for power sallied forth to their orgy.

Precisely because the old nationalism assumed an adversarial relationship toward the norms and institutions to which most Americans adhered, it could locate few forces in American society with which it could join, and it therefore came to rely almost entirely on a centralized state as the only “nationalizing” instrument available for its mission. Hence, the old nationalism was intimately bound up with abstraction, alienation, the serving of special rather than authentically national interests, and the consolidation of state power against its own society.

What a new, Middle-American nationalism must seek is a redefinition of nationalism away from the terms of the old. Since a Middle-American nationalism bases itself on the actual interests and norms of a concrete social group, it will not display the same adversarial alienation that affected the pseudo-nationalism it seeks to replace, nor will it need to rely on the power of the national state to the same degree or in the same way. Nevertheless, the mission of the new nationalism must be not merely the winning of formal political power through elections and roll-call votes but also the acquisition of substantive social power and the displacement of the incumbent managerial elite of the regime by its own elite drawn from and representing the Middle-American social stratum. No social group becomes an elite unless it makes use of the instruments of force that are at the heart of the state, and hence, a Middle-American nationalism cannot expect to achieve its goals unless it employs the state to reward its own sociopolitical base and exclude its rivals from access to rewards. A Middle-American nationalism must expect to redefine legal rules, political procedures, fiscal and budgetary mechanisms, and national policy generally in the interests of Middle Americans, and it must do so with no illusions about rejecting, decentralizing, or dismantling the national state or the power it affords. Middle-American interests are dependent on the national state through various educational, fiscal, trade, and economic instruments, and a Middle-American nationalism ought to announce an explicit agenda of consolidating and enhancing these instruments. At the same time, a new nationalism must recognize that many of the organs of the national state exist only to serve the interests of the incumbent elite and its underclass allies—the arts and humanities endowments, and most or all of the Departments of Education, Labor, Commerce, Housing and Urban Development, and Health and Human Services, and the civil rights enforcement agencies in various departments—and it should seek their outright abolition, as well as that of those agencies and departments in the national security bureaucracy that serve globalist and anti-nationalist agendas.

But power based merely on the state is insufficient for the reconstitution of American society under Middle-American dominance. State power indeed, though a prerequisite for the emergence of a new elite, is by itself a weak support, and it must be supplemented by cultural dominance. Under the incumbent elite and its regime, characteristic Middle-American norms of sacrifice for and solidarity with family, community, ethnicity, nation, religion, and morals, and their rules of taste and propriety, are under continuous attack, subversion, and delegitimization by the cultural and intellectual vanguards of the elite. In place of such norms, the elite offers an ethic of hedonism, immediate gratification, and cosmopolitan or universalist dispersion of concrete identities and loyalties, an ethic that serves the interests of the incumbent elite by encouraging a passive and homogenized (though fragmented) culture of continuous consumption, distraction, entertainment, self-indulgence, surrender of social responsibilities to mass organizations, and the erosion of the concrete social identities and intermediary institutions that restrain the centralized manipulative power of both political and corporate structures.

By far the most strategically important effort of an emerging Middle-American counterelite would be a long countermarch through the institutions of the dominant culture—universities, think tanks and foundations, schools, the arts, journalism, organized religion, the professions, labor organizations, and corporations—not only to assert the legitimacy of Middle-American cultural and ethnic identity, norms, and institutions but also to define American society in terms of them. Instead of an ethic of acquisitive individualism, immediate and perpetual gratification, distraction, and dispersion, the new nationalism should assert an ethic of solidarity and sacrifice able to discipline and direct national energy and reinforce national, social, and ethnic bonds of identity. The pseudo-nationalist ethic of the old nationalism that served only as a mask for the pursuit of special interests will be replaced by the social ethic of an authentic nationalism that can summon and harness the genius of a people certain of its identity and its destiny. The myth of the managerial regime that America is merely a philosophical proposition about the equality of all mankind (and therefore includes all mankind) must be replaced by a new myth of the nation as a historically and culturally unique order that commands loyalty, solidarity, and discipline and excludes those who do not or cannot assimilate to its norms and interests. This is the real meaning of “America First”: America must be first not only among other nations but first also among the other (individual or class or sectional) interests of its people. Unless a Middle-American nationalism (or any other sociopolitical movement) can achieve such cultural hegemony through the formulation of an accepted public myth, its political power and economic resources will remain dependent on the cultural power of its adversaries and eventually will succumb to their manipulation as it takes its cues on goals and tactics from its opponents.

If a new Middle-American nationalism is in some respects a synthesis and a transcendence of the conventional poles of right and left, it is also in another sense a resolution of the polar conflict between the classical republicanism and the nationalism around which so much of American political history has swung. Like the nationalist tradition, it concerns itself with the pragmatic defense of national interests in foreign affairs, military security, and political economy, but unlike the old nationalism it perceives a national interest beyond this pragmatic dimension in the preservation of the distinctive cultural and ethnic foundations of nationality, recognizing that pragmatic, material, and economic considerations may and should defer to the more central norms without which pragmatism is merely a meaningless process. The affirmation of national and cultural identity as the core of the new nationalist ethic acquires special importance at a time when massive immigration, a totalitarian and antiwhite multiculturalist fanaticism, concerted economic warfare by foreign competitors, and the forces of antinational political globalism combine to jeopardize the cultural identity, demographic existence, economic autonomy, and national independence and sovereignty of the American nation. Like the republican tradition, the new nationalism is essentially populist in tactics, locating the cultural and moral core of contemporary American society in a stratum that is the main victim of the regime that now prevails in the United States.

Like republicanism also, it is less interested in the abstract pursuit of luxury and empire than in the defense of the characteristic norms and identity of the people it defines and represents, and like republicanism it calls that people to a duty higher than mere accumulation and aggrandizement, to a destiny of knowing who they are, where they came from, and what they can be. If they remain able to answer that call, they and their posterity may yet achieve both a virtue and a power that neither old republicans nor old nationalists were ever able to create.

Leave a Reply