With Republicans increasing social spending and Democrats upping military outlays, Washington is devoid of serious debate over any important issue. Despite the President’s attacks on GOP “isolationism,” both parties largely favor foreign intervention. As a result, America finds itself entangled in almost every international conthet and potential conthet: Bosnia, the Caucasus, China, Colombia, East Timor, Greece, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Kashmir, North Africa, North Korea, Russia, Taiwan, and Turkey.

And then there is Kosovo. The coalition that claimed to be conducting a war against ethnic cleansing included NATO member Turkey, which has leveled an estimated 3,000 Kurdish villages and displaced as many as two million Kurds in a guerrilla war that has killed 37,000. NATO’s “humanitarian” warriors also stood by in 1995 when the Croatian military, trained by U.S. advisors, kicked hundreds of thousands of Serbs out of ancestral lands in the Krajina region, shelling and strafing refugee columns. And the allies voiced not a peep at the murder of 6,300 people in Sierra Leone in January 1999 alone, more than triple the death toll of the previous year in Kosovo.

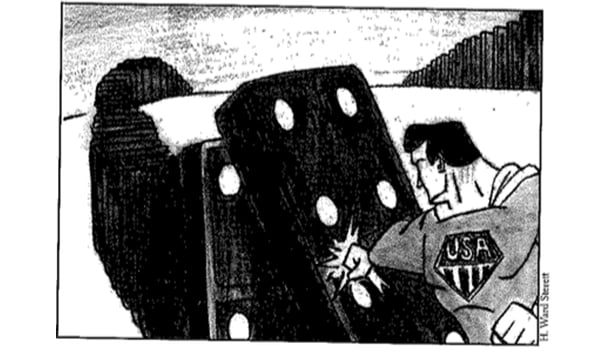

For half a century, foreign policy centered on the principle of containment. The result was the creation of an oversized military, backed by a global network of bases and military deployments, and manned through conscription. But ten years ago, the Berlin Wall fell, the Warsaw Pact dissolved, the Soviet Union collapsed, and the threat of aggression dissipated. In short, almost the entire foundation of American foreign policy was gone.

Yet no serious reconsideration of U.S. foreign policy has occurred. The Clinton administration would like to do everything, calling its policy “enlargement.” Every Asian alliance must be preserved, NATO must be expanded, and elsewhere the administration has engaged in what Michael Mandelbaum of Johns Hopkins has called “foreign policy as social work”—attempting to mend failed states and squelch ethnic hatreds. After Kosovo, the President even announced that the United States would stop ethnic cleansing in Africa and elsewhere, although his national security advisor, Sandy Berger, immediately began backpedaling.

The Republican alternative has been incoherent. The GOP favors maintaining all existing alliances. Support for South Korea should be strengthened, cooperation with Japan should be deepened, and NATO should be expanded. The only questions are how far and how fast. Republicans also back increased military spending. Although there has been some dissent on more extraneous commitments, enough GOP leaders supported military action in Bosnia, Haiti, Kosovo, and Somalia that opposition was limited largely to ineffective protest. In principle, both parties favor Pax Americana, although they sometimes disagree about where and when to act.

The American people spent more than $13 trillion (in current dollars) to defeat the Soviet Union. Yet all of the institutions of containment remain in place; the Cold War military establishment is intact. Not one alliance has been dismantled; not one commitment has been eliminated. On the contrary, the U.S. government has increased guarantees and deployments almost exponentially: American planes bomb Iraq around the clock; troops are deployed in Bosnia, East Timor, Macedonia, and Kosovo; Azerbaijan is angling for a U.S. base; Uzbekistan wants military relations with NATO; and even longtime enemy North Korea is suggesting that the United States transform its troop presence into a neutral peacekeeping mission.

This globalist campaign to contain nothing is expensive, costing nearly $300 billion annually. Military spending is the price of an aggressive foreign policy: The more there is to do, the more forces and weapons are needed. In inflation-adjusted terms, Washington is spending as much on the military today as it did in 1980—during the Cold War. Outlays remain as high as in 1975, when we were coming out of the Vietnam War, and even 1965, when we were going into Vietnam. Today, America accounts for about one-third of the world’s military outlays—a far higher share than during the Cold War. America spends more than three times as much as Russia, eight times as much as China, and twice as much as Britain, France, Germany, and Japan combined. U.S. “defense” spending equals that of the next ten countries, and is 17 times as much as the military expenditures of the “rogue nations” (Iraq, North Korea, et ai).

The United States suffers an economic disadvantage as well: America devotes roughly four percent of its CDP to the military, twice as much as Germany and four times as much as Japan. The result is a de facto subsidy to leading trade competitors, which means that U.S. taxpayers and businesses support research, development, and investment in other nations.

Intervention is also risky. Although the potential consequences of war have dramatically diminished since the demise of the Soviet Union, very real dangers remain. The Kosovo war resulted in confrontation with both China and Russia and strengthened India’s commitment to an independent nuclear deterrent. The Korean peninsula could still erupt in war. Washington’s implicit security guarantee to Taiwan could lead to conthet with China. Attacks on small countries like Yugoslavia will grow more dangerous as biological, chemical, and nuclear weapons spread. Unfortunately, wars rarely turn out as expected.

It is one thing to accept these risks as the price of protecting American security; it is quite another when the risks are run to advance the interests of other countries. Yet the three most obvious situations in which America could be drawn into a major war today—Iraq versus Kuwait/Saudi Arabia, China versus Taiwan, and North Korea versus South Korea—all involve threats to U.S. allies rather than to the United States.

The price of intervention is also paid in human lives. America’s Balkan war was unique in its lack of U.S. battle casualties. However, America’s overwhelming military preponderance is likely to prove transitory as other nations close the gap. Indeed, should the Kosovo occupation degenerate into a desultory civil war, Americans will see body bags coming back from overseas. It is all too easy to be humanitarian with other people’s lives.

The lives may not be only those of members of the Armed Forces. Terrorism today is largely a response to U.S. intervention abroad. The World Trade Center was bombed because of Washington’s policies in tire Middle East. Terrorism is a means by which relatively powerless groups or nations can strike the globe’s only superpower.

As we move further into the post-Cold War world, the United States could develop a new, expansive, interventionist foreign policy that justifies maintaining a Cold War military; or America could adopt a restrained foreign policy and cut military commitments, deployments, and spending accordingly.

Some advocates of the first course see new enemies everywhere. NATO expansion is obviously directed against Russia. While the rise of nationalism (spurred, alas, by the West’s own actions, particularly NATO expansion and the war on Serbia) is worrisome, the Moscow Humpty Dumpty has fallen off of tire wall and cannot be put back together again. Russia is only about two-thirds the size of the old Soviet Union, its economy has imploded, and its armed forces have deteriorated dramatically. The British, French, and Germans today spend more on the military than does Russia. Moreover, if those most at risk, the Europeans, feared a revived Russia, they would not have been cutting military spending. Washington’s proper response is watchful wariness. There is no need to preserve a military created to defeat the Soviet Union in order to deter an anemic Russia.

China is also an unlikely enemy. The nation with the world’s largest population may eventually enjoy the world’s largest economy; it will eventually become more influential in other dimensions, including the military. China may very well become the most dominant nation in East Asia. But Chinese preeminence in Asia does not necessarily threaten the security of America. Conflict is likely only if the United States attempts to maintain its hegemony ever)’where, including along China’s borders.

It is difficult to imagine any other likely U.S. enemies. Germany and Japan have neither the ability nor the incentive to threaten America. Brazil, Indonesia, and India are important countries with significant long-term potential, but whatever threats they could conceivably pose in the future do not require military confrontation today. Nor do their interests seem likely to clash catastrophically with those of the United States.

Most of the arguments, then, for a leading military role today involve having the United States play something akin to globocop, acting as the world’s 911 dispatcher. That has certainly been the case during the Bush-Clinton era: Among military actions in Bosnia, Haiti, Kosovo, Kuwait, Panama, and Somalia, only the war against Iraq offered even the pretext of the national interest being at stake. The rest were attempts to impose a new domestic political regime or international settlement on disorderly or failed states.

The result has not been pretty. Somalia remains divided among warring clans. The United States managed to move Haiti from a military to a presidential dictatorship. In Bosnia, Western occupation, not popular consent, holds together three hostile parties in an artificial state. Panama’s government may he less hostile, but appears to be no less corrupt. In Kosovo, the killing continues, only now by ethnic Albanians.

Another argument for intervention is that the United States has to demonstrate “leadership.” Former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich once acknowledged that America could cut its defense budget in half if it did not have to “lead” the world. But American leadership, given this nation’s economic and cultural influence, is inevitable. There is no reason why “leadership” must be predominantly military. Indeed, real leadership requires the use of discretion in deciding when and how to act, rather than intervening everywhere on behalf of everyone.

Real leadership also requires humility. Nobel Prize-winning economist F.A. Hayek wrote of the “fatal conceit” of social planners, which is at work in U.S. foreign policy today. What is this fatal conceit? The belief that Washington has the wisdom and ability to order events in distant societies without regard to history. The belief that one can loose the dogs of war and control where they run. The belief that U.S. political leaders have the moral authority to use military force whenever they desire to engage in international social engineering.

Ironically, Washington’s abusive and arrogant “leadership” may ultimately limit American influence by encouraging other nations to cooperate in order to constrain U.S. power. Both China and Russia are prepared to resist American hegemony. India has begun to move closer to its old enemy, China, to forge a countervailing coalition. During the war against Yugoslavia, New Delhi lauded its nascent atomic arsenal as a means of keeping the peace, a comment clearly directed at the world’s sole remaining superpower; Indian hawks are pressing for a significant nuclear deterrent capable of striking America. In time, these nation—along with more independent European states, like France, and emerging powers, like Brazil and Indonesia—may actively oppose pretentious U.S. claims to global “leadership.”

The most serious argument for American intervention in Kosovo was humanitarian. Yet it was quite impossible to take the administration’s moralizing seriously. Death tolls in the millions (Afghanistan, Angola, Cambodia, Sudan, Rwanda, Tibet), hundreds of thousands (Burundi, East Timor, Guatemala, Liberia, Mozambique), and tens of thousands (Algeria, Chechnya, Congo, Kashmir, Sierra Leone, Sri Lanka, Turkey) are common. The estimated death toll in Kosovo was exceeded even by the number of dead in Northern Ireland’s sectarian violence. Yet in none of these cases did Western leaders rise to express the outrage of the “international community,” let alone propose taking action. (In September, Australia led a number of states in establishing a peacekeeping force in East Timor, but Canberra acted only with the consent of Jakarta and after standing by during a quarter-century of mass violence in the territory.

Similarly, 7.5 million people have fled violent strife in Africa. Over the last decade, hundreds of thousands of people have been displaced from Armenia, Azerbaijan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. The government of Bhutan “cleansed” more than 100,000 ethnic Nepalese in the 1990’s. There are 3.6 million refugees in the Middle East. In these cases, too, the supposed guardians of human rights have been almost entirely silent.

Perhaps nowhere is this cynicism more evident than in the case of Turkey. Like Serbia, Ankara regards separatist guerrillas as terrorists. A quarter-century ago, Turkey invaded Cyprus, created a Turkish zone, and “ethnically cleansed” its occupied territory of some 165,000 ethnic Greeks. Like Serbia, Turkey speaks of protecting its ethnic co-nationals from violence. Yet the United States not only treats Ankara as an ally; it provides many of the weapons which Turkey has used to prosecute its wars, and Washington enlisted Ankara in its crusade against ethnic cleansing in Kosovo.

There is an alternative to this policy of promiscuous meddling. It could be called many things—nonintervention, strategic independence, or military disengagement—but not isolationism. America can, and should, be highly engaged internationally, maintaining an open economic market, compassionately accepting refugees and immigrants, spreading art, music, and other cultural goods, and cooperating politically.

The philosophical point is simple: The duty of the U.S. government is, first and foremost, to protect its own citizens, their lives, freedom, and property, and the system of ordered liberty in which they live. It is not to meddle abroad in pursuit of even good ends. The lives and property of Americans are not gambit pawns for politicians to sacrifice in some global chess game.

Washington believes that the United States could reshape the world if only we could amass enough power and resources. This presumes that Washington policymakers know more than everyone else, and that other peoples, governments, and nations are shapeless lumps of clay, anxiously waiting to be molded.

This theory has proved disastrous. Consider only the experience of this century. The Treaty of Versailles sought to remake the world; two decades later the system came crashing down, as most of the globe was engulfed in a terrible war. American meddling in Vietnam, Iran, Nicaragua, Iraq, Somalia, Haiti, Zaire, and elsewhere has only added to human misery.

When assessing a conflict that seems to require U.S. intervention, policymakers have asked, “Why not?” when they should have asked, “So what?” They should assess whether the “what” affects vital, important, or only marginal interests. Their response should vary depending upon the importance of the interest at stake. A threat to the nation’s very survival—à la nuclear war with the Soviet Union—is very different from an isolated instance of chaos within chaos—say, a three-way civil war in Liberia. The first requires official action; the second does not Washington also needs to assess whether other actors can handle regional contingencies. Surely South Korea, with 30 times the productivity and twice the population of North Korea, is capable of defending itself So is Japan. And Europe.

Even if the only possible response is U.S. military action, policymakers should still weigh the costs and benefits of getting involved. Perhaps Europe was unwilling to act in Kosovo without the United States. But any serious weighing of costs and benefits would have militated against intervention.

America should vigorously defend its vital interests. But Washington should accept that the world will be a messy place, and that not all messes can be cleaned up—certainly not by the United States. We should cooperate with the United Nations or other states when it is advantageous to do so, but we should not sacrifice our own interests to those of other international actors. In the end, the United States should be the distant balancer, not the immediate meddler.

As America’s foreign policy changes, so should its force structure. Instead of spending $280 billion a year on die military, Washington could spend $1 50 billion. Instead of keeping 1.4 million people in uniform, America could lower its troop strength to 850,000. Rather than 11 carrier groups, the United States could get by with six. This would still leave America with the largest, most advanced, and most effective military on earth, capable of defending itself and cooperating with friendly states to preserve shared interests.

The United States enjoys many advantages and will remain a superpower almost in spite of itself Washington should remain engaged and even exercise leadership, but it should not hector, control, or impose on other nations. In short, America should return to a foreign and military policy befitting a republic, rather than an empire. In this way, the United States would best preserve its independence and freedom.

Leave a Reply