If radical Afrocentrists have their way, soon all schoolchildren will learn—as some are now learning—a version of ancient Mediterranean history that gives credit for the Greek achievement to the ancient Egyptians. The Afrocentrists contend that what most people have learned about the origins of Western civilization is untrue. According to them, the ancient history we have studied is a concatenation of racist lies designed to prevent the world from knowing the true extent of the African contribution.

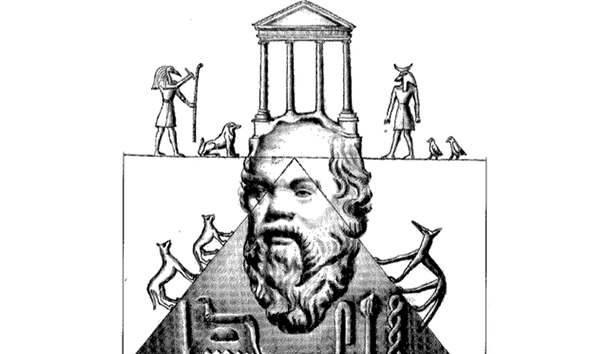

The notion of a conspiracy of European historians allows Afrocentrists to make other specific claims about the past. They insist that the Greek people have African origins, and that Aesop, Socrates, Hannibal, Terence, and Cleopatra did as well. Even more importantly, they assert that Greek philosophy was Egyptian philosophy, that after studying in Egypt, the Greek philosophers returned home and passed off what they had learned as original contributions of their own. In particular, they contend that Aristotle went to Egypt with Alexander, stole books from the Alexandrian Library, and put his name on them.

How true are these claims? It is relatively easy to show that most of them are false, supported by assertions about possibilities rather than evidence. For example, the claim that Socrates had African ancestors is based entirely on the fact that he is shown with thickish lips and a snub nose in portrait sculptures. But these features are hardly exclusive to people of African descent. And certainly the comic poets would never have stopped teasing him about his foreign origins, if he had had any. Greeks, and especially Athenians, were always somewhat suspicious of people from outside their own city-states, still more of foreigners.

The idea that Cleopatra was black is also based on conceivable possibility. No one knows the identity of her paternal grandmother, who was her grandfather’s mistress. Because her family always associated with other Greeks, everyone has always assumed that this unknown woman was Greek, either slave or free. If she had not been Greek, someone would have certainly pointed it out.

The claim about Aristotle is even more insubstantial. Did Aristotle really steal his philosophy from Egypt? Until relatively recently, no one ever thought so. What, after all, was the evidence to support such an assertion? No ancient writer thought that Aristotle ever went to Egypt, or had much contact with Alexander after he left Macedonia. Also, how could Aristotle have stolen his books from the library of Alexandria? He died in 322 B.C., and the library was not assembled until at least 20 years after his death.

There is no reason to assume that the Egyptians had much influence on Greek religion or Greek philosophy, until some time after 300 B.C., after the Macedonian Greeks had conquered Egypt and after the deaths of both Plato and Aristotle. After the Greeks and Egyptians had coexisted for some centuries, Greek writers became more familiar with Egyptian mythology and religion. But even then they seemed to understand only those aspects of Egyptian belief that corresponded most closely to their own ideas of the universe, and they expressed themselves in the abstract vocabulary developed by Plato and Aristotle.

Not that radical Afrocentrists are persuaded by these arguments, or any other arguments, just because they arc based on warranted evidence. Perhaps 30 years ago arguments from evidence might have carried some conviction. But these days they are less effective. People no longer judge an argument on the basis of facts, but on the basis of cultural motives. These are the motives which are thought to arise from being part of an ethnic or geographical culture or subculture. Therefore, if you are a historian of European descent, it is assumed that you will naturally want to favor other European cultures. As a result, your account of ancient history can be regarded as biased by members of another cultural group.

Criticisms of this sort cannot be automatically dismissed. Some of them are even justified. It is completely reasonable to argue that the study of the civilizations of ancient Egypt and Nubia has been neglected in favor of Greece and Rome, and to observe that the Greco-Roman way of doing things is not always superior to the Egyptian. The Greeks themselves completely misunderstood the deeply spiritual nature of the Egyptian gods, who manifested themselves in different forms, including those of animals. The Greeks found such “animal worship” deeply uncongenial, and made fun of the Egyptians for the respect with which they treated certain animals, including cats. But considerable harm has been done to animals because of the European belief that only human beings have souls.

The radical Afrocentrists also have reason to complain that many European scholars have not sufficiently emphasized that the ancient Egyptians were an African people. According to Herodotus, who had visited Egypt, the Egyptians were dark-skinned and woolly-haired. His portrait of the Egyptians appears to be supported by archaeological evidence that suggests that Egyptians were brown-skinned and had dark wavy hair. Their gene pool contained both southern African and Semitic elements. It is probably fair to say that if a person from Memphis, Egypt, in 1930 B.C. turned up in Memphis, Tennessee, in A.D. 1930, he would have had to sit at the back of the bus.

No one should blame the Afrocentrists for pointing out that European historians have overlooked the question of Egypt’s connection with other peoples on the African continent. Also, they are certainly right to observe that Europeans, beginning with Herodotus, have given only a disjointed account of the Egyptians’ religious beliefs and practices. The problem is that the radical Afrocentrists are not interested simply in promoting more study of ancient Egypt, however reasonable that goal. For example, they do not point out that the ancient Egyptians distinguished themselves from the Nubians, who lived further to the south, and from the Phoenicians, Hebrews, and Philistines. Their physical characteristics were not identical with those of African people from whom they were separated by natural divisions of geography, such as the peoples of West, Central, and South Africa.

In fact, the radical Afrocentrists arc not interested in ancient Egypt as it actually was. Instead, the Egypt they want all children to learn about is a distinctively Europeanized Egypt, invented first by Greek travelers to that country and later elaborated on by Europeans in the 18th century. Most ironically, the Egyptian philosophy that the Greeks were supposed to have stolen was originally Greek.

The earliest descriptions of academics for Egyptian priests. with large libraries and art galleries, occur not in any ancient text, but in an 18th-century French work of historical fiction, Séthos by the Abbe Jean Terrasson, first published in 1731. Terrasson’s novel was widely read, and it had a profound influence on portrayals of Egyptian religion in later literature, and in works such as Mozart’s Magic Flute.

Séthos had a particularly lasting effect on Freemasonry. Since 18th-century readers regarded Terrasson’s account as basically factual, the Masons based their initiation rituals on the ceremonies and trials that Terrasson’s hero underwent in his training as an Egyptian priest. It is from these rituals, and from the Freemasonic notions of their own origins, that the radical Afrocentrists derive their notion that there was an elaborate Egyptian mystery system in antiquity. They assume that the Greek philosophers came to Egypt to learn about this mystery system and that it was practiced at the Grand Lodge at Memphis and at other subordinate lodges.

But the idea of an Egyptian mystery system is an anachronism no less farfetched than the notion that Aristotle robbed the Library of Alexandria. There were no “mystery” or initiation cults in Egypt until the Greeks settled in Alexandria in the third century B.C., after Alexander’s invasion. The “mystery system” in Terrasson’s novel, which formed the basis of Masonic ritual, was derived entirely from Greek and Roman sources; only a few aspects of the ritual he describes are authentically Egyptian. The basic narrative is patterned on the experience of the heroes of Greek and Roman epics.

It is completely understandable that Terrasson relied on Greek and Roman writers. He had no other choice. Before the 1830’s, when the Egyptian writing on the Rosetta Stone was deciphered, no one had access to any authentic Egyptian materials, because no one could read any of the Egyptian scripts. And of course the Masons, who do not pretend to be serious scholars, did not revise their rituals and notions of their own history in the light of the new information about Egypt that became available once hieroglyphics could be read.

Why do the radical Afrocentrists still maintain that there was an “Egyptian Mystery System,” when in fact it has been known for more than 150 years that no such thing ever existed? The answer, in large part, is that they would like it to be true, because it gives an African civilization credit for the greatest achievements of human history, the development of philosophy and of scientific thought. But in so doing, they overlook the fact that they are assigning to an African people the primary blame for many of the troubles that they blame on European rationalism.

The notion of a conspiracy also has great appeal. It makes the history of Egypt conform to the later pattern of European aggression against Africa. It offers a poignant explanation of why Africa’s intellectual culture has had only a small impact on the rest of the world. Since Egypt stands for all of Africa and peoples of African descent, it enables African peoples to regard themselves as innocent victims.

Because the idea of a “Stolen legacy” allows peoples of African descent to take pride in their heritage and to feel morally and culturally superior to the Europeans who have persecuted them, the myth has a positive function. Ultimately, however, it will do much more harm than good. It can only increase resentment against peoples of European descent and widen a rift that is already difficult to bridge. But even more importantly, it should not be taught as history in schools because it is not historical. Rather, it is a form of propaganda, designed for a particular political purpose. It is not at all surprising that this notion of a “Stolen Legacy” seems to have been developed in the 1920’s and 30’s, at the same time that new histories of Germany and Italy were being written in Europe, and no one should need to be reminded of the harm that was done by the nationalistic myth of the Master Race.

The proponents of Afrocentric history ought to realize that they are giving carte blanche to other groups, of whose motives they would definitely not approve. If one group can rewrite history to suit itself, why not another? And in the conflict that will inevitably result between opposing views, who is likely to win? The loudest voice, or the voice with the most money behind it?

The only way to prevent such chaos is to stick to the known facts and to build arguments on the basis of evidence. Such a debate about the Egyptian and Near Eastern legacies to the West has been going on in the academy for more than a decade. Some of the discussion has been generated by the claims of Martin Bernal’s Black Athena: The Afroasiatic Roots of Western Civilization. But even before Bernal published the first volume of his series in 1987, scholars had been reassessing the evidence.

The picture of the ancient world that emerges from this recent work is infinitely more nuanced and varied than the one some of us learned in school. Of the neighboring cultures, those located on the Eastern side of the Mediterranean, such as Phoenicia, appear to have made the greatest impression. That the Greeks were in communication with foreign cultures docs not mean that the “Greek Achievement” was fundamentally the product of foreign influences. Rather, the point is that Greek writers and thinkers in different periods were able to learn from their neighbors. Even though Egypt had only a limited influence in earlier periods, new research shows that after Alexander conquered Egypt, Greek and Egyptian civilizations had an influence on one another, in literature and art as well as in philosophy and law.

Instead of concentrating on the myth of the “Stolen Legacy,” which is in itself a relic of the European Enlightenment, Afrocentrists should turn their attention to the Egyptian influence on Greece and Rome during the period 300 B.C. to A.D. 400. Then they could make a historical case for an African contribution to Western Civilization.

Leave a Reply