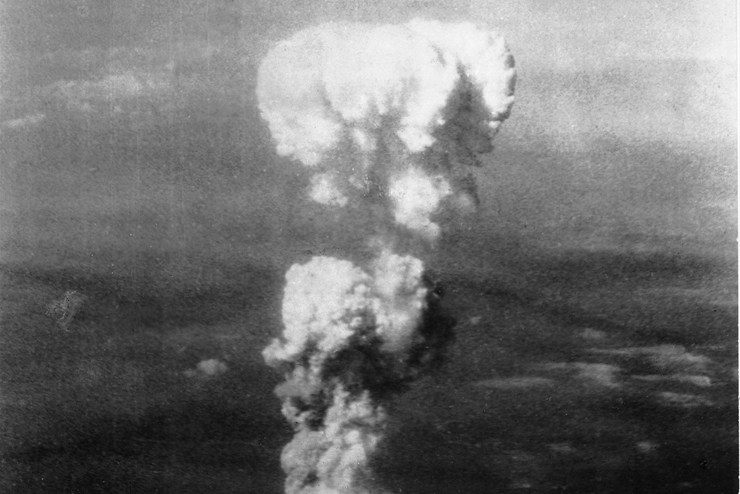

I was rather taken aback by Fr. Brian W. Harrison’s letter in the September issue of Chronicles (Polemics & Exchanges: “Evil That Good May Come”). He could not have been more mistaken. Fr. Harrison asserts that the dropping of the atomic bomb on Japan was unnecessary because the Japanese were effectively defeated and were ready to surrender, given a few small concessions on the part of the United States. He further states that the attack was intrinsically evil and morally unjustifiable due to the massive death toll of Japanese noncombatants.

We don’t know and can’t know if the bombs were unnecessary. As the four articles published in Chronicles (“The Bomb” August 2020) prove, there are various and conflicting opinions on the subject. God alone knows if we were right in what we did.

Regarding God, I will remind Fr. Harrison that it was God who commanded the Israelites to slaughter, en masse, the Caananites in the land he had promised them. And Scripture says that Christ (therefore God) is the same yesterday, today, and forever. The God of the New Testament is the God of the Old. Therefore it cannot be said unequivocally that the atomic bombing of Japan deserves God’s condemnation.

Scripture also tells us that we should not rely on our own understanding, but in all our ways we should acknowledge Him and He will direct our paths. Can we, with certainty, state that President Truman and others responsible for making the decision to drop the atomic bombs on Japan, did not seek God’s wisdom before committing such an unprecedented and world-changing act? Let’s hope that they did. That too, is something only God knows.

—Edward Stansell

Clifton, Tenn.

Unionized Minds

Having been made aware of Catholic Confederates: Faith and Duty in the Civil War South through John M. DeJak’s intriguing review in Chronicles (“Catholic Comfort for a Wounded South” September 2020), I now eagerly look forward to the arrival of my own copy. If Mr. DeJak’s review is any indication, Gracjan Kraszewski’s book is a worthwhile addition to a terribly neglected dimension of American Catholic history.

For my part I would only add that whenever we consider the “Confederatization” of antebellum Catholics in Dixie we must also keep in mind the “Unionization” of ourselves. That is, regarding the controversies preceding the war, the winning side really did get to write an oversimplified history. Thus, very few today would dare publicly question the righteousness of a movement which never repudiated psychotic terrorist killers like Nat Turner and John Brown, much less admit that the Christian tradition’s attitude toward slaveholding is a little more complicated and nuanced than that of, say, Frederick Douglass.

In any event, for the benefit of interested readers, Bishop Martin J. Spalding’s Dissertation On The American Civil War (1863) and Bishop Augustin Verot’s Slavery & Abolitionism (1861) demonstrate that there were indeed pro-Confederate bishops who looked earnestly to Catholic heritage as they reflected upon the moral and spiritual challenges posed by “the peculiar institution.” For Spalding and Verot, the right response to the long-standing fact of slavery lay with Catholic ministry, whereby everybody’s welfare—blacks included—might be gracefully, gradually promoted, up to and including the possibility of eventual emancipation.

In contrast, the abolitionist response to the slavery issue was a catastrophically violent and disorienting revolution which enshrined centralized, post-constitutional government in the name of equality. That the abolitionists won out must be why so many African-American communities in 2020 are so happy, wholesome, and flourishing, especially in places like Chicago and Detroit.

—Jerry Salyer

Franklin County, Ky.

Mr. DeJak replies:

There is much to commend in Mr. Salyer’s letter. Most intriguing is his observation of the “unionization” of ourselves since the Civil War. A fair assessment of the historical record requires one to shed modern assumptions as distinct from philosophical and theological conviction. To be sympathetic with the actions of one in the past requires a maturity that goes beyond simplification of “the good guys vs. the bad guys.” I think Kraszewski does that in his volume; when he mentions “Confederatization,” he does so in terms of certain Catholics ignoring papal documents or the few times when they put emphasis on politics rather than the spiritual.

Reasonable minds can and have differed on the complicated and nuanced history of slavery in the world and its immediate or gradual eradication. The ultimate issue is whether one has the philosophical conviction that a human person can be the property of another. If one agrees that cannot be the case, then discussion of its eradication will ultimately be one of tactics.

America is in crisis and has lost its original constitutional moorings for several reasons, in my view. These include the re-casting of the United States as a propositional nation, which ignores the cultural and legal soil from which it arose. This is coupled with the overreach of the executive branch of government and a public atmosphere that embraces egalitarianism.

At the same time, as constructs of men, all forms of government have the tendency to go off the rails. The desuetude of authentic natural law thinking in the 19th century and the failure to adhere to the English legal tradition may have contributed to the creation of the federal leviathan after the Civil War.

The Conservative Mood

In “Rebranding the Right,” (October 2020 Chronicles) reviewer Timothy Lusch has it right when he pinpoints the foundational conservative hallmark as a “disposition.” Moreover, Lusch’s assessment of the strands of conservatism stands in marked contrast to editor Andrew Bracevich’s selective representation of it. Lusch writes:

Conservatism is neither a brand nor a political ideology. It is a disposition, a way of being in the world that by necessity, manifests itself in politics. And the political arena…is no place for ideological purity tests. (Emphases mine.)

And that is why Whittaker Chambers, perhaps the one-time most visible prototypical exemplar of conservatism’s “disposition,” initially rankled National Review over his reticence to align with a political philosophy. Chambers called himself a “man of the right” in contradistinction to an orthodox conservative. Erstwhile strictures and staunch tenets of conservative orthodoxy were not part of Chambers’s “lived conservatism,” to use Lusch’s succinct locution.

But what exactly was the disposition of Chambers’s conservatism that illustrates Lusch’s point? To be sure, Chambers was an empiricist-realist, a pragmatist, and an autodidact. An empiricist-realist because he disavowed communist ideology when he discovered that its orthodoxy didn’t match the facts. He was a pragmatist in two ways—in farming and in journalism. On the family farm, he employed skillful agricultural methods, succeeded in dairy production, and practiced animal husbandry. As a journalist and essayist with Time, Life, and National Review, he scrupulously sifted through the research to write peerless, compelling essays.

As an autodidact and student of a classical education, Chambers was a polyglot fluent in at least three languages and literate in several others, including Russian. But it was his literacy in history that made Chambers a prescient observer of historical movements and trends. He was regarded by his admirers as the consummate purveyor of historic events past and present with a keen perspective on their meaning and predictability.

A conservative disposition necessarily includes an expression of spiritual faith and conviction (sans orthodoxy in Chambers’s case; he belonged to the Quakers Friends Church), acknowledgment of the sanctity of the nuclear family, the value of the work ethic, and a sense of pride and gratitude in ownership of private property and good land.

While all the foregoing composite traits ascribed to Chambers might exceed a minimalist conservative disposition, definitely these characteristics trend towards the Chambersian exemplification of what the essence of conservatism is all about.

—Robert Doriss

Watkins, Colo.

Image Credit:

above: Atomic cloud over Hiroshima [Image by: George R. Caron, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons, cropped and resized]

Leave a Reply