Yesterday brought us another Presidents’ Day, when government, schools, and certain businesses close up shop while retailers offer some of the year’s best sales. Officially, however, there is no “Presidents’ Day.” The federal government still designates this holiday as “Washington’s Birthday.”

Here’s how this confusion came into play. Until 1968, the nation recognized Feb. 22, George Washington’s birthday, as a legal holiday. In that year, the Congress passed the Monday Holiday Laws, which created our current system of three-day weekends and which also set aside the third Monday in February as Washington’s “birthday.” Not only did this alteration of the calendar ensure that the holiday would never occur on February 22, it also meant that the moveable date would always fall between Washington’s birthday and Lincoln’s, which is Feb. 12.

In a relatively short time, retail advertisers and popular usage renamed the holiday “Presidents’ Day,” which at first alluded to the combined birthdays of Washington and Lincoln, but was then extended to honor and celebrate all presidents. So, while the federal government still officially recognizes “Washington’s Birthday,” most of the country abandoned that honorific for the fuzzier notion that all our presidents deserve a bit of spotlight.

One custom still attached to the Feb. 22 date takes place in the U.S. Senate. Since 1896, on every Feb. 22 a senator reads aloud George Washington’s 7,641-word Farewell Address in its entirety. The senator then records his name and a few remarks in a black, leatherbound book which has been used for this purpose since 1900. In his 1956 note, for example, Democratic Senator Hubert Humphrey urged all Americans to study Washington’s address. “It gives one a renewed sense of pride in our republic,” he wrote. “It arouses the wholesome and creative emotions of patriotism and love of country.”

This address also invites us to hear George Washington’s cautions regarding partisanship and regional divisions, entangling foreign alliances, and the critical place of religion, morality, and virtue as foundation stones for the newly-established republic’s success. He warned, for instance, against a wholly secular government, writing

…let us with caution indulge the supposition that morality can be maintained without religion. Whatever may be conceded to the influence of refined education on minds of peculiar structure, reason and experience both forbid us to expect that national morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle.

We moderns chiefly remember George Washington for his actions as commander-in-chief who led the Continental Army to victory against the British, the president who successfully navigated the uncertain waters of a new, unique form of government. He deserves that appreciation, but we often forget that his contemporaries honored him as much for his character as his accomplishments.

In his book George Washington’s Sacred Fire, in which he labors to refute modern claims that Washington was a Deist and not a Christian, Peter Lillback writes, “A careful study of Washington’s use of the word ‘character’ shows that it was profoundly important to his view of human conduct. The word itself appears almost fifteen hundred times in his writings.”

And in one of appendices to this biography Lillback includes 47 reflections on Washington written between 1774 and 1821 by Americans and international figures, most of whom personally knew him. Their descriptions of him echo one another again and again with words like integrity, virtue, honesty, sound judgment, patience, and humility.

Whether we celebrated Presidents’ Day on Feb. 17 or waiting to celebrate Washington’s birthday on Feb. 22, which this year happens to fall on a Saturday, we should set aside a portion of the day to reflect both on the man who was eulogized as “first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen” and on the extraordinary times in which we ourselves now live.

We, too, are in the midst of a revolution, a rebellion against an oppressive government that for the past four years, and in less severe fashion for decades earlier, sought to limit the liberties and powers of its own people. We should resist any urge to rue the age in which we live, for we are surely put here to work, each of us in our own way, great and small, to preserve our freedoms and to pass them along to our children.

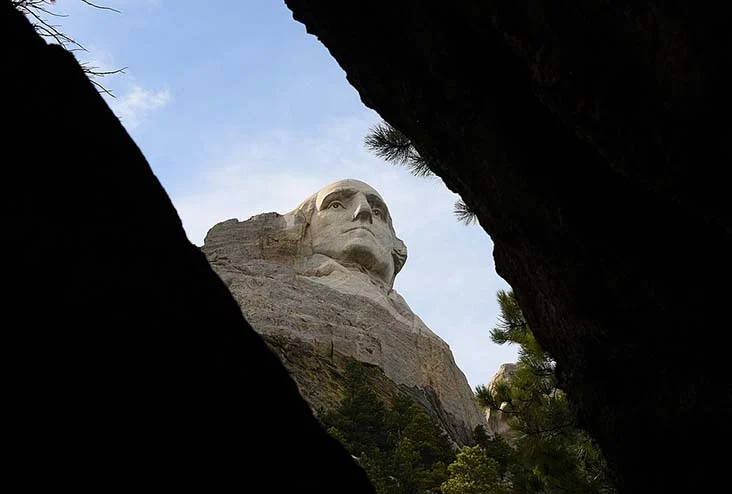

On this holiday, then, let’s honor George Washington by learning a little more about him, by teaching our children his story—the Mount Vernon website offers everything from virtual tours to educational resources—and by vowing to keep close watch on our Constitution and our natural rights.

Leave a Reply