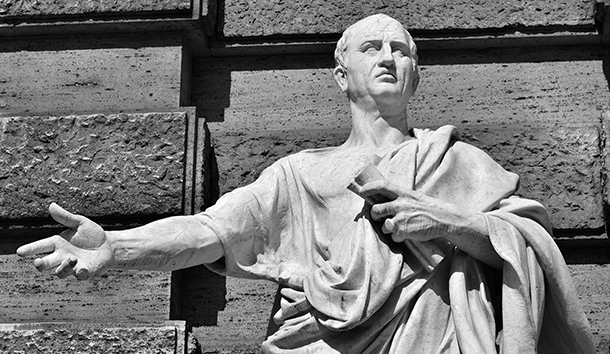

Cicero wrote De Officiis to his son, Marcus, a student of philosophy who had just finished his first year in Athens. Though Cicero does not state it directly, the work is meant to supplement what, to his mind, Greek philosophy lacked most: good practical sense and the principles of action. He sought to fuse Greek philosophy with Roman civic duty. Marcus, being in his formative years and having the promise by birth of a prominent role in Roman politics, was an appropriate recipient for such instruction.

But Cicero no doubt had more than Marcus on his mind. Writing in the tumultuous time between Julius Caesar’s assassination and Marc Antony’s political rise (which led to Cicero’s own assassination), Cicero sought the restoration of the Roman Republic and civic virtue, and the eager youth were crucial to achieving that end. De Officiis was a letter to future civic leaders.

In Book I, Cicero calls marriage the prima societas. Children naturally follow, and together they form una domus, communia omnia (“a household with everything in common”). The desire for the domus, which he calls a “gift” of nature, comes by natural instinct, and this domestic society is the “foundation” or “nursery” of civil government. With the formation of domestic society comes responsibility, especially the responsibility of the head of the household—the paterfamilias—to manage and provide for his family. This responsibility, says Cicero, “stimulates his courage and makes it stronger for the active duties of life,” including public civic service conducive to the common good. The household, well-managed and well-supplied, is of paramount importance for the cultivation of civic virtue. The man of the house is essential for political and social order.

The few young men today who yearn for the restoration of the classical household (or at least some form of it) lack a modern guide to set them on the right path. There is a sense of loss among us and a lack of direction. As an “old Millennial” myself, I can speak to the feeling of homelessness or lostness of our generation—the aspirations for ephemeral authenticity, the never-ending search for and dissatisfaction with stability and permanence, the striving for meaning by destroying meaning, and the anticonsumerist consumerism. Marriage is rejected, and children are an afterthought. Home, as a place of settlement, dwelling, and permanence, has succumbed to the house of market value. There is no generational love of place; there are only places for sale, catering to our consumptive habits, and whose supply of authentic goods when dried up precipitate a thoughtless exodus to the next place of promise.

Many of us have recoiled from these trends and see where they are heading, and yet we have no handbook to instruct us out of it. Too many books on young life, marriage, and childrearing—from the secular self-help books to the Christian life manuals—offer sentimental garbage, leave unchallenged the worst of the bourgeois excesses of our time, or apologetically dance around the concept of authority and the nature of masculinity. Where is the wisdom for our age?

A recent book of wisdom, written by a Presbyterian pastor in Connecticut, gave this old Millennial a good, stern truth-thrashing. Man of the House, by C.R. Wiley, is a work I will read and read again and give to my sons. Like Cicero, Wiley wrote it “for young men everywhere” in dire times. Let’s hope that it is read everywhere, as it deserves to be, and not too late.

Wiley calls his work a “handbook” on “building a shelter,” one that is much more than a physical structure. It is a “plan of action.” This sounds like “prepping,” and to some extent it is, as Wiley admits—preparation “to help you survive the long slow” decline of civilization. But while this prep-talk might serve as a useful hook for potential readers, tapping into a certain malaise common among some conservatives, much of the wisdom in the book is timeless, requiring no failing civilization to make it relevant. Indeed, this sort of “sheltering” simply amounts to living well.

Wiley is refreshingly honest, even blunt at times. Allan Carlson, who wrote the book’s Afterword, approvingly refers to some of Wiley’s writing here as “politically incorrect”—and it is. But the directness of the text is what young men need and want. I’m convinced that many such men, starving for some direction in masculinity, want an older man with gravitas and wisdom to give it to them straight—no fluff, no weak talk, and no sentimentality.

Wiley begins with the “framework of a household,” which is established in marriage. In marriage a man receives the title of husband—the “house-bound”; and the wife receives his name. The household is a place of giving, sharing, and love—a place of intimate striving for the common good in accordance with each person’s household role. Though children do not constitute the household, they do perfect it, further uniting husband and wife, increasing the mutual giving, and linking generations as each proceeds through the various stages of life.

Wiley then describes the material basis of the household, proclaiming that “Productive property is a school of virtue.” The key here is the modifier productive: that which produces some good or service. Productive property “places you in a position to be a net contributor to the common good.” Today, residential properties are usually sites of consumption—eating, sleeping, amusement. They hardly produce anything at all. Modern work has driven both men and women from the home to sites of mere production. The traditional household was, however, a unique and distinctive place for both consumption and production—a dwelling of domestic life in all its variegated demands, obligations, and responsibilities.

Americans now consume themselves with thoughts of getting and keeping a job (or, as Millennials tend to do, searching for the next one). We seek after an employer and a wage; we enter the labor market to sell our labor-time. We lose our independence in the commute, in our “careers,” and in our insecure and unstable jobs. We are in the age of “flexible” capitalism with a “generalist” labor pool in which there is no permanence, only the anticipation of unpredictable change and disruption. Wiley’s response to the status quo is truly countercultural: “Turn your job into a trade school. . . . [M]ake the household the center of productive enterprise once again.” Bring work home. Restore your independence.

Wiley also discusses justice, gravitas, and piety as they relate to households. Justice is equity, not equality: Each person deserves what he or she is due, and not everyone is due the same. The father, being the “best equipped” to lead the household, is the leader. He is the mighty one of the household. But with power comes responsibility—“might must serve right.” This requires gravitas, which refers to the “weight” of one’s presence among others. They feel it when a man enters the room or addresses them, as with Cicero’s Scipio Africanus in De Republica. “You want it,” Wiley observes. But how does a young man acquire it? Put on some muscular weight, exercise self-control, be independent, eschew pride, know when to walk away and be capable of doing so. Come to understand the concept of the “weight of glory” (which Wiley illustrates with a fine selection from Tol kien’s Lord of the Rings). These are but a few elements of gravitas described in the book. Obviously, the sorts of Millennials who don man-rompers need to read this, yet these are important insights for all young men, even those who are now wearing glorious beards. The rejection of the modern pathologization of masculinity is prone to excesses and needs direction.

Piety is, for Wiley, what links the household to the cosmos and the members of the family together, including the dead, the living, and the unborn. It is an honoring of those who are worthy of honor. The man of the house as the leader is set apart as deserving peculiar honor, and he must not be so small-souled as to undermine his own authority and the respect it is due. Humility ought never to destroy the natural order of things. In their various roles, the members of the household honor one another and, in so doing, honor God. Together, the household honors God, His creation, the family’s ancestors, and people outside the household.

Wiley then connects the sovereign household to civil society, which, properly speaking, is composed of households. Anyone who loves the modern state and large-scale capitalism might accuse him of being overly devoted to the ancestral household gods and giving short shrift to those of the city. But his practical advice—gain property and stay put, mind your own business, make government redundant, defend yourself—is directed against modern life, not against civil life as such. He envisions, so it seems to me, Alexander Chayanov’s peasant utopia, a network of small-scale productive households characterized by order, liberty, and limited governance. Civic virtue then arises from productive households as they relate one to another, fostering the common good.

But we don’t live in that world—at least not at the moment. Attempts to reestablish productive property face serious challenges, both from an economy unrelenting in cost-cutting and its pursuit of maximized efficiency and from the administrative state. Yet the global order and the administrative state are beginning to come apart at the seams. Indeed, they are unsustainable, as anyone familiar with the truths of the natural order, which Wiley so brilliantly illustrates, will recognize. Wiley sees in the inevitable self-destruction of the welfare state an opportunity for the household economy to become viable again.

The Rev. C.R. Wiley is no Cicero, as he himself would no doubt insist. Yet he has provided for today’s generation exactly what Cicero provided for his, answering the call of young men for guidance. He has also provided hope for men who are ready to reject today’s culture of sentimental outrage, serial house-flipping, and meaningless work—and its stultifying effects on God-given masculinity. The household economy, led by the man of the house, is the way forward.

Leave a Reply