To judge from the corporate media’s fawning presentation and careful omissions of former Vice President Kamala Harris’s stated positions in the 2024 election—one would have been hard pressed to know that that many of her views have very little support among the American people. Perhaps the most glaring of these omissions is Harris’s position on reparations for slavery.

Harris has straightforwardly stated that as president she would have led a national conversation on the necessity of reparations. Meanwhile, nearly 7 in 10 Americans says “No” to reparations, including majorities of every major racial group except blacks. Even on a purely partisan basis, the issue is hardly a winner in political terms. Democrats are evenly split on the issue.

When the Florida Board of Education passed new standards in 2023 for the teaching of the history of slavery, Harris expressed outrage that “middle school students in Florida [were being] told that enslaved people benefited from slavery … They insult us in an attempt to gaslight us.” Florida governor Ron DeSantis responded by accusing Harris and others who adhere to her position of deception in the interest of furthering “their agenda of indoctrinating students.” Harris’s view of slavery and its consequences is uncomplicated, to say the least. The new standards, in DeSantis’s analysis, are simply informing students that some liberated slaves learned skills in their time as slaves that were useful in their later lives.

DeSantis’s point is perhaps worth exploring, in the interest of showing just how complex the consequences of slavery have been and how little substance is present in the argument for reparations. It would seem tobe an undeniable point that at least some of what slaves learned and did as slaves in the way of knowledge of labor, however unfortunate the conditions under which they acquired that knowledge, might have served them in their lives as free citizens once slavery ended. And we know that slavery as an institution was also quite more complicated in other ways than the simplistic narrative of the radical activists. In a guest essay at Glenn Loury’s Substack, for example, Robert Cherry succinctly summarizes the accounts of some celebrated historians of the institution (e.g., Robert Fogel, Herbert Gutman, and Eugene Genovese) who found that lives of American slaves involved rather less material deprivation than is commonly asserted in the woke activist understanding of slavery.

Of course, these points do not negate the overarching question of the immorality of slavery. That institution involved treating some human beings as the property of others in a polity that purported to be founded on the unalienable right to liberty common to all men. But acknowledging what slaves learned as part of their experience in spite of the immorality of the institution does not whitewash slavery itself. It simply seeks to make the conversation on slavery presented to students more complicated than the existing hyper-simplistic discourse on the woke left. It also emphasizes the agency of those who were enslaved, instead of treating them always as completely helpless pawns of powers beyond their control. This is a positive thing, if we think about the pedagogy of the young as centrally concerned with showing them how complex the world can be.

Clearly, at the level of the individual former slave, the disadvantage conferred by having been enslaved is much greater than any useful job skills he or she might have acquired as part of that negative experience. But how would the trajectories of African slaves in America and their descendants, as a population, have been different if the trans-Atlantic slave trade had not existed? Is it certain that things would’ve gone better for them in that scenario?

The American slave population as a whole, and especially their descendants born after the institution was extinguished, probably experienced better general outcomes than would have been likely if they had not been put on those ships bound for the Americas.

American slavery, we are told in the narrative championed by woke elites, was uniquely monstrous and horrible—certainly the worst possible thing that could have happened to them, and the condition of nothing but future suffering for their descendants, and this is why reparations are necessary. What possible argument can exist that those who suffered this unmatched evil and their ancestors might somehow have been still worse off without it?

The question of seriously taking on the problem requires one to engage in counterfactual history. We know what became of slaves and their descendants as a result of their coming to America. But we do not know what would have happened to those Africans who were brought to the U.S. as slaves if slavery had not existed in the Americas.

Almost no one on either side of this debate seriously entertains this question these days, but it can be seriously entertained.

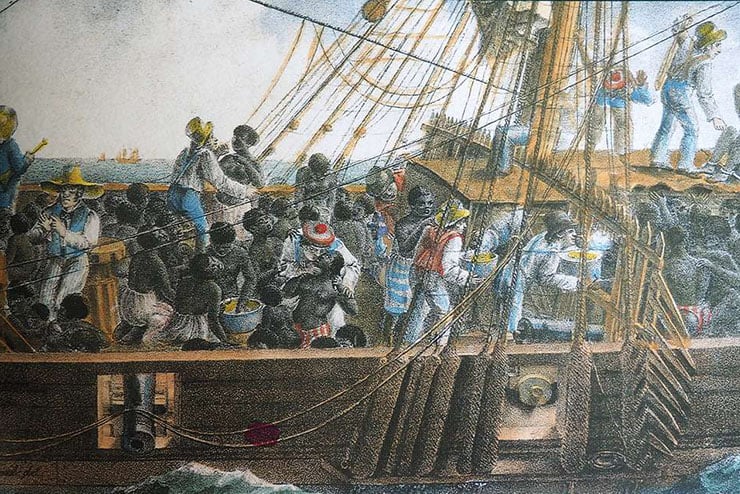

One is obliged to begin by noting that nothing that follows is intended to downplay the truly abominable aspects of the transatlantic slave trade or American slavery. Perhaps as many as 2 million perished en route from Africa. Many who arrived in the U.S. died soon thereafter. The conditions of unfreedom of the institution had massive physical, psychological, and cultural impacts on the people involved. No one who is aware of this history can deny any of that.

But let us explore some of the possible counter-histories.

It must first of all be acknowledged that the disappearance of slavery in the Americas would not have erased slavery from Africa. Many of those who wound up on ships in the transatlantic slave trade might, had that route to bondage been eliminated, instead have found themselves on slave ships in the Indian Ocean bound for the Middle East. Many others would have been taken over land routes through the Sahara to North Africa to be sold in the Arab slave markets. In the absence of a Western slave trade would certainly have meant many more Africans enslaved in the Muslim world. In fact, even with the competition of the Western slave trade, the Muslim trade in African slaves was, in the view of some scholars, significantly quantitatively larger.

The Trans-Saharan slave trade was particularly perilous, as it involved travel by land in tremendously inhospitable climate and environment. Some estimates are that for every sub-Saharan African slave who made it through the Sahara, perhaps three or four others perished or escaped and were lost in the desert during the journey. Would such a dismal fate of dying in the desert to leave no descendants have been better than the experience of a slave in North America, who suffered all the many indignities of the institution but whose ancestors later became the free, and comparatively prosperous African-Americans of today?

Slavery was a lucrative business not just for slave traders headquartered outside Africa, but also for African leaders, who used war captives and criminals to sell to the Westerners. At least some of those in the transatlantic slave trade would, in our counter-history, have wound up as slaves in the myriad internal African slave networks. Some of these systems were quite different from chattel slavery, but chattel slavery also existed in Africa. In Western Africa, the part of the continent from which most of those slaves in the Atlantic trade originated, slavery was quite common. It endured there long after the U.S. abolished the slave trade and the institution it fed.

But let us assume a counter-history with no forms of slavery. In that case, many of the people who became slaves, those who in their native lands were frequently criminals or war captives, likely would have been put to death by civil executioners or sacrificed in accordance with indigenous religious and cultural rituals. Human sacrifice was a widespread phenomenon in Africa during the period of the slave trade. In some parts of the continent, ancestor worship required that at least some of the slaves of any deceased individual be killed and buried with him. In Western Africa, the regional powerhouse Kingdom of Dahomey engaged in an annual ceremony in which hundreds or even thousands of slaves and war captives were decapitated and sacrificed in worship of the deceased kings of Dahomey.

Might things have turned out better for those for whom the alternative to slavery in America was something like this?

Still another angle requires no counter-factual history. If we carefully consider the actual trajectory of African slaves in America and their descendants we can still see that things ended better for most.

In comparative terms, there is no population of people of sub-Saharan African ancestry that is economically better off in 2025 than American blacks. The median annual income for black Americans is nearly $50,000. This figure ranks them wealthier than the vast majority of the rest of the planet. Of the world’s 14 black billionaires, eight are Americans. If black America were a separate country, it would rank in the top 25 of all the world’s countries in terms of per capita income.

By contrast, every single one of the West African countries in which those descended from American slaves have their origins is struggling economically. Indeed, the average African-American income is nearly four times higher than the average income of even the best performing African country. None of the West African countries show an average income of more than $3,000. The average person in many of these countries lives on an annual income that is less than 1/20th of the average African-American’s income.

So, how much better off would those contemporary descendants of American slaves have been, at least in purely economic terms, if their ancestors had stayed in their desperately impoverished homelands and if those contemporary descendants still lived there today? The answer to this question, at least, is obvious. Unless they were lucky enough to be among the economic and political elite in those countries, they would have been far worse off in Africa than in America.

This is only the beginning of an inquiry into the fascinating question of whether and how the descendants of slaves in America might have benefited from the fact that their ancestors were brought here. Again, none of this negates the injustice done to those slaves or amounts to an attempt to beautify the unlovely fact that slavery is nothing to celebrate. Yet history works itself out in complicated ways. The long-term consequences of any given event or phenomenon are often surprising and confounding.

Leaving aside the question of where the money to pay reparations to the descendants of African slave in America would come from, the idea of paying those reparations to people separated by more than a century and a half from an institution with such a complicated set of consequences is rather hard to defend on moral grounds. Fortunately, Harris lost, and so she will get no opportunity to advocate from the White House on this or any of the other divisive and morally unserious proposals she defends. But there are many others in the American public sphere who continue to advance a case for reparations.

The far left is not going to abandon this issue just because Harris lost. Conservatives should inform themselves about the kind of facts described above to prepare themselves to resist this ill-considered idea on factual and rational grounds.

Leave a Reply