Ever wonder why your representative voted in opposition to an issue supported by a majority of his constituents? It may be because he is secretly more accountable to illegal donors than he is to his voters. Recent research by Vote Your Vision, a national election integrity organization, suggests that illegal campaign contributions through identity theft are much more common than is generally known, and are likely the largest factor undermining the quality of democratic representation provided by our politicians.

“Smurfing” is a money laundering technique where large sums of illicit money are broken down into smaller, less noticeable transactions to evade detection by regulatory authorities. Recently, there have been numerous reports that smurfing has been used to launder illegal contributions to political campaigns through identity theft. Criminals do this by identifying someone who made contributions in the past (usually a senior citizen), and then they make hundreds or thousands of small dollar donations in that person’s name to a particular campaign or candidate, thereby evading campaign contribution limits. Tens of thousands of people across the country are victims of this form of identity fraud in every election cycle, and thousands of candidates (whether knowingly or not) have benefited from these types of illegal contributions.

Unusually high numbers of contributions are an indicator of this kind of fraud, so to explore the extent to which smurfing influences campaigns and politicians, Vote Your Vision developed a software tool that uses publicly available data from the Federal Election Commission to identify individuals who have made more than 100 separate contributions in any election cycle over the last 10 years. [Note: The data we downloaded from the FEC for the tool is a snapshot in time, and has some anomalies when compared to data accessed directly from the FEC’s website, so it should be used solely to identify potential smurfing that can then be followed up by accessing the latest records for an individual directly from the FEC website.]

Using the tool, we discovered strong indicators for campaign finance fraud and identity theft in all 50 states and the District of Columbia.

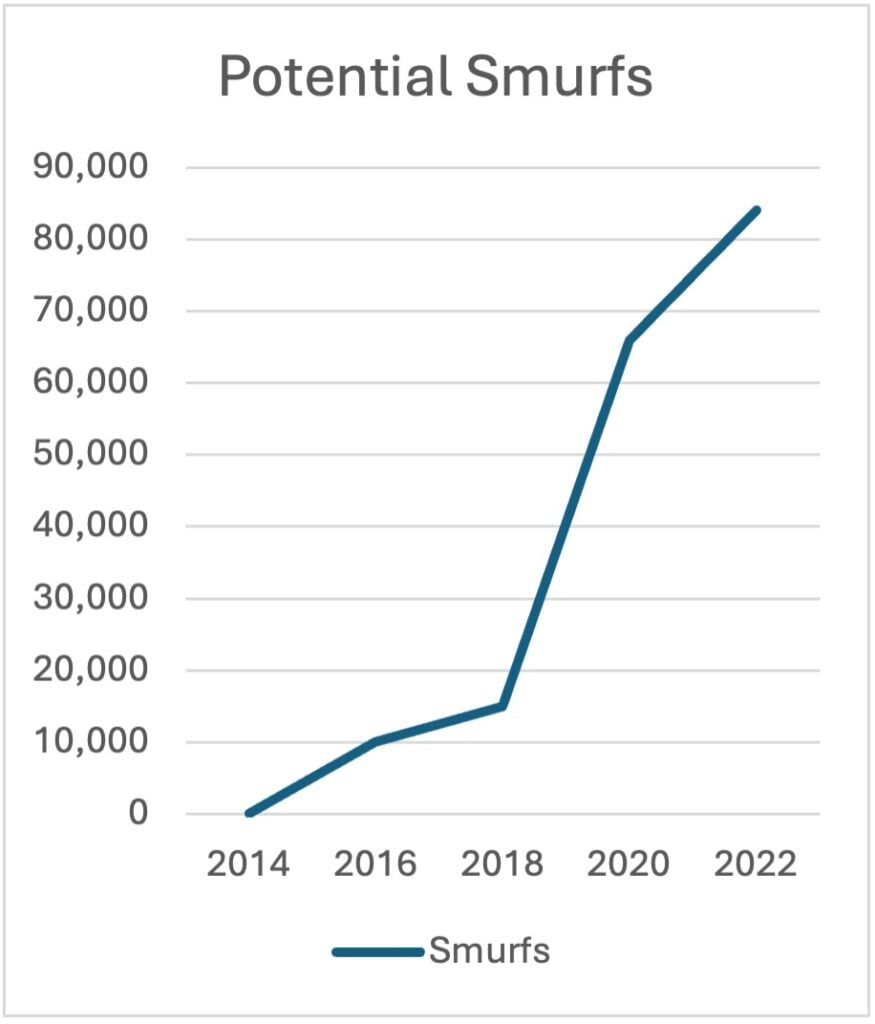

Our data suggest that smurfing began taking off as a tool for laundering illegal cash into campaigns at some point after the 2014 election cycle. In the 2014 cycle we found just 58 people who donated more than 100 times. Since then, we saw a steady increase in the number of potential smurfs detected in each election—rising to 84,000 in 2022, which is the last election cycle for which we have complete data. At the time the data was collected for this study (early July 2024), there were already 26,000 potential smurfs for the 2024 election cycle, and that total is likely to grow significantly as we get closer to the election.

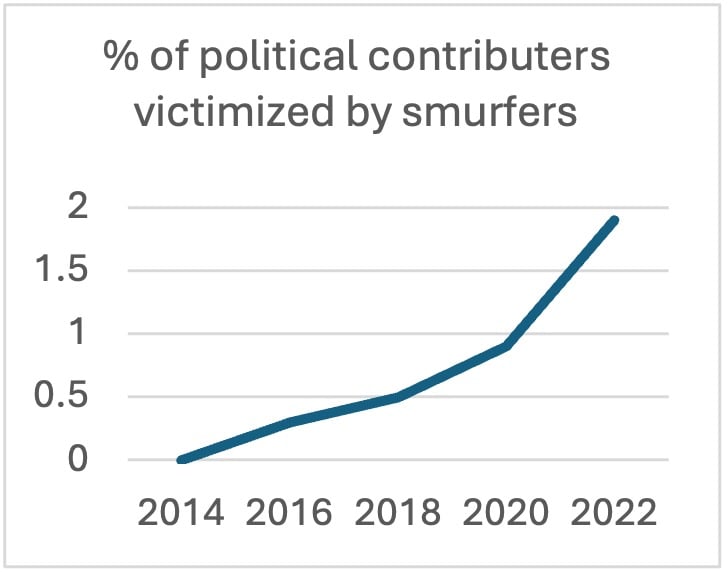

The percentage of political campaign and candidate donors whose identity has been stolen by the criminals—and who have unknowingly become smurfs—has also steadily increased, from virtually zero in 2014 to almost 2 percent of all donations in 2022. That means if you have ever contributed to a political campaign or political action committee (PAC), there is a not insignificant possibility that your identity has been stolen. The probability is even higher if you are over 65 years old.

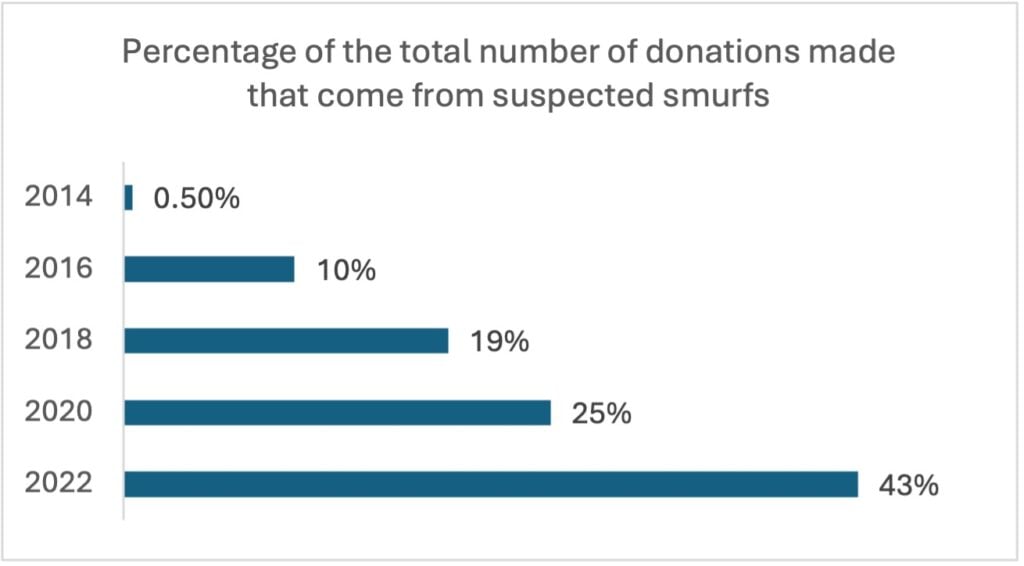

While the number of smurfs in the donor pool tops out at about 2 percent, their percentage of total donations is much higher, as they typically make donations of thousands and sometimes tens of thousands of dollars each.

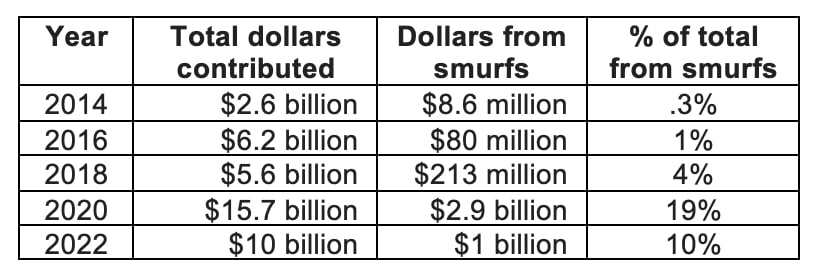

When we consider the potential impact of these illegal torrents of campaign contributions, the most important factor is the dollar amount.

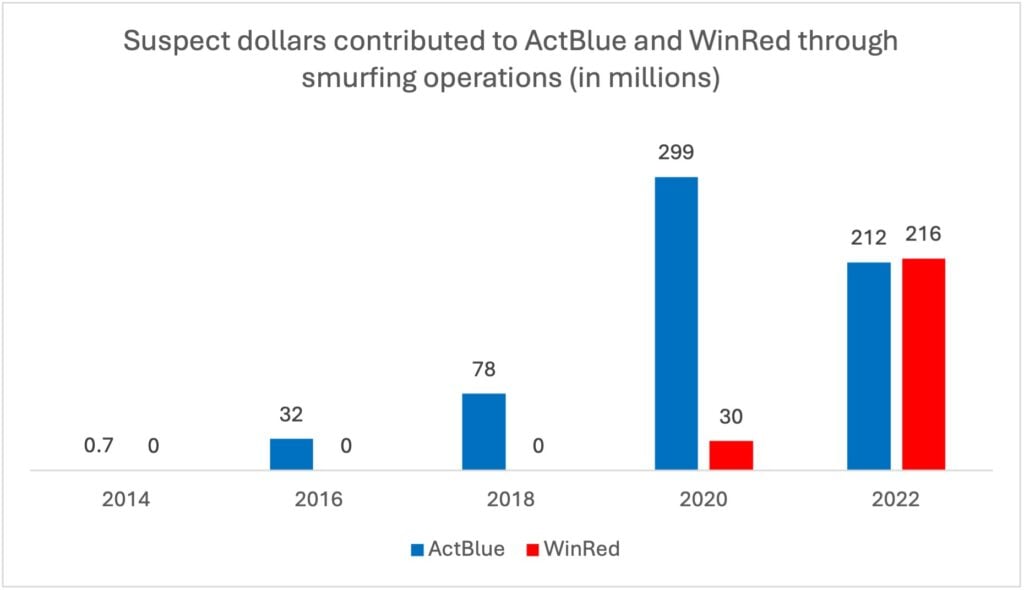

In the table on the right, you will see that the total funding contributed to campaigns in the last decade has increased massively, with mid-terms almost doubling with each cycle, and funding in presidential years more than doubling. But as rapid as that growth has been, it is nothing compared to the exponential growth we see in the amount of that funding that is potentially illegally channeled into campaigns from smurfing operations.

In 2020, almost a fifth of all campaign contributions may have come from smurfing operations, channeled through the stolen identities of vulnerable elderly people. And while increasing funding by a fifth would provide a massive boost for any campaign, that is not how the funding is distributed. Instead, it is targeted, and so has much greater impact. Most constituencies in the U.S. are uncompetitive and will reliably elect either a Democrat or a Republican in cycle after cycle, so many political donations have little impact on electoral outcomes. But all of the illegal cash dumped into the system by smurfs will directly target elections in play, and so will have much greater impact on outcomes than the mere percentage of total contributions in this category suggests.

As a Republican, I started the research expecting to find most of the fraud on the Democratic Party’s side, but that was not the case. When we looked at who the most prolific smurfs in the top 10 smurfing states donated to, we found 14 contributed to Republicans and 16 to Democrats. So we dug deeper. A large percentage of donations from smurfs typically goes to the party PACs WinRed and ActBlue (with the rest distributed to campaigns and PACs across the country), so we used the party PAC as a proxy to get an estimate of how each party benefited from smurfing operations.

WinRed didn’t really get started until the 2020 cycle, when they raised a total of $896 million, with 3.3 percent (about $30 million) of that coming from potential smurfing operations. By 2022, the Republican-leaning smurfers had ramped up, potentially supplying about 25 percent ($216 million) of the $867 million WinRed raised that year. In retrospect, given the number of Republican legislators who act contrary to the preferences of their constituencies, perhaps I should not have been surprised. ActBlue, on the other hand, has been around since at least the 2014 cycle, and we have data for them going back to that year. Less than one percent of their funding came from potential smurfing operations in 2014, but that rose to 9 percent in 2016, 11 percent in 2018, 14 percent in 2020 and 18 percent in 2022.

There have been enough documented cases of the laundering of illegal campaign contributions—also known as smurfing—to be sure that it exists. Our findings based on a cursory review of publicly available data suggest that smurfing is much more common than people realize, that the problem is growing, and that our elections and the quality of the democratic system are being massively degraded. More in-depth analysis would certainly provide more certainty and granularity concerning who receives, and who gives, this illegal money.

Unfortunately, we have neither the investigative mandate nor technical proficiency in database analysis to do that, but you know who does? The Federal Election Commission. They have the mandate, the data, and the analysts. Unfortunately, they don’t seem to have the interest. It is almost preposterous to believe that no one at the FEC ever noticed the massive money laundering evident throughout their data. Their utter failure suggests either corruption or incompetence.

I would recommend that Congress investigate this issue, but it seems likely that Congress itself should be investigated, as every single member that received contributions from ActBlue or WinRed, or directly from smurfs. Even if they knew nothing about the illegal funding, it could have influenced the outcome of their races. The same can be said for the presidential candidates, and it would be surprising if similar smurfing is not affecting elections in the states.

Smurfing works because it allows millionaires and billionaires to unfairly affect elections and governance by providing illegal funds for their preferred candidates. But it also has an even more insidious potential, as it allows a smurfer to approach a candidate or officeholder and offer to top up their war chest in exchange for a favor on an upcoming bill. Smurfing compromises and co-opts politicians who are meant to represent all of their constituents, not just the richest few.

To learn if smurfing is happening in your neighborhood, or if you yourself are a victim of smurfing, use this “Check Your Zip!” tool at Vote Your Vision which uses publicly available FEC data to identify individuals in your zip code who have made reportable contributions more than 100 times in any election cycle. When I did this for my zip code, I found a retired 81-year-old woman two streets away who had made over 4000 contributions in the 2022 cycle alone and had “donated” more than $100,000 to campaigns and candidates across the country.

To save our republic and restore actual representation of the people and not the oligarchs, we must eliminate corruption in campaign finance. The FBI should immediately launch investigations of the FEC and Congress for smurfing corruption and track these contributions to their sources. Both WinRed and ActBlue, and any other PAC found engaging in smurfing, should be shut down until the perpetrators of the fraud are identified and prosecuted. A reformed FEC must put safeguards in place to eliminate smurfing and the other forms of illegal contributions that undermine America’s democracy.

Leave a Reply