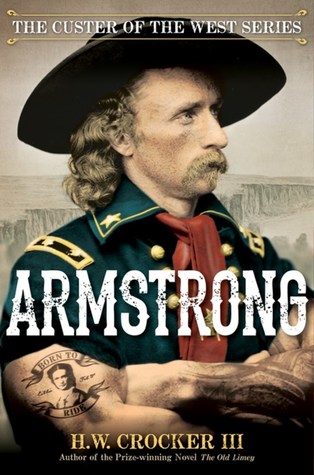

Armstrong is a rollicking work of alternate history that doesn’t sacrifice accurate details or historical nuance for the sake of your entertainment.

Have you ever wondered what might have happened if General Custer survived the Battle of the Little Bighorn? Wonder no more, for this is the premise of Armstrong. H.W. Crocker III immerses you right alongside Custer, telling the tale in Custer’s voice to let the reader in on all the shades of hilarity, nobility, and vanity that conspire to make up the infamous general.

Through the pen of Crocker, Custer paints himself as “a knight errant,” and he lives up to this title in similar style as another knight errant, Don Quixote. Though he’s a much better rider than the infamous Don, he shares the passion for noble quests and the obliviousness to inconvenient, unromantic details. “Logistics,” for Custer, “never deter audacity.” Nothing inspires Custer’s bravery or nobility more than a beautiful woman, with whom the book is laden—and there is none more beautiful, we are told, than the unseen Libbie, the wife to whom Armstrong is written.

Armstrong finds Custer miraculously rescued by the American wife of a Sioux Indian from the field of Little Bighorn, where he and his troops were betrayed into disaster. After the two escape Indian custody, Custer finds himself in the town of Bloody Gulch, Montana. This town is controlled by the nefarious Largo Trading Company, who has broken up and enslaved the local families and employed an army of Sioux Indians to keep the town under control while the Company hunts for a legendary treasure of Confederate gold. Custer, inspired by duty to defend the defenseless, springs into swashbuckling action under the alias of U.S. Marshal Armstrong Armstrong.

It all ends well, but the story will convince you otherwise along the way, and distract you with jokes too many to count before you’re done. Crocker gives continuity to the motley cast of cancan dancers, Southern gentlemen, and Indian scouts with running gags, including constant translations of Billy the Crow, a Crow Indian scout who was converted to Christianity by a priest. (In French, petre; in Spanish, sacerdote; in Latin, sacerdos.) Several recurring moments cater to the mind’s eye – for instance, Custer’s reflexive fumbling for his tooth-brushing kit whenever an especially attractive lady is present.

The gags are spaced out enough that they’re familiar yet fresh each time, and several of the most comic are founded in fact. Custer did drink milk in lieu of any alcohol, after a violent drinking incident that threatened his reputation as a suitor for the hand of his wife-to-be, and did refer to it as “Alderney” after an English cattle breed. He did have a special touch with animals, though whether the real Custer believed horses spoke French and dogs spoke German is unclear—it works for the Custer of Armstrong, though, to hilarious effect.

Crocker uses alternative history to tell truths of real history, and offers a particularly interesting peek into the post-civil war period by not focusing on the reconstructed South—rife as it was with social, economic, and especially racial tensions—but on the ripple effects in the Midwest. Armstrong is set in the late 1870s, which, for context, is towards the end of Reconstruction, after the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments have been ratified, Grant is president, and six African-Americans hold seats in the House of Representatives. Crocker, who has more than proved himself in both military and Civil War history with Don’t Tread on Me and Robert E. Lee on Leadership, shows us command of historical context with less flash and more nuance.

For example, in Armstrong, Custer mentions acting as best man to a Confederate officer during the war, which is true. Crocker lets Custer occupy some grey area, lending some dimension to the black and white dichotomy between North and South. When asked if he’s still “against the South,” Custer replies:

“I was never against the South, ma’am; I was ordered to prevent their secession; and after the war I kept the peace . . . I took a vow at West Point to defend the Union; I could not fight against it.”

Crocker also explores the overlap between red and blue, between Republicans and Democrats.

Armstrong’s Southern sidekick, Beauregard Gillette, turns out to be a federal agent, despite convincing Armstrong he was a “committed rebel.” As a federal agent, Gillette is loyal both to President Grant and Grant’s Republican party. The former Confederate Gillette and the Union officer Custer break the stereotypes of Democrats as Southern slavist scumbags and Republicans as infallible and virtuous angels, giving readers an opportunity to see where the parties once fell on matters other than slavery. Custer waxes eloquent over a glass of Alderney:

“What this country needs is a good Democrat in favor of lower taxes, a return to sound money, free trade, a smaller, reformed government that spends more on the army, and honest administration—especially after two terms of that baboon Grant.”

Crocker’s Custer is larger than life, but if there’s anything that’s worth exaggerating, it’s commitment to chivalry and duty. You might not get misty-eyed at thoughts of driving chickens down Main Street, or think that cancan dancing will redeem high society, but you’ll still find in Armstrong’s Custer a hero to love and admire.

[Armstrong, by H.W. Crocker III (Washington D.C.: Regnery Fiction) 256 pp., $27.99]

Grace Houghton is a student at Hillsdale College and a former intern at the Conservative Book Club, where this review first appeared.

Leave a Reply