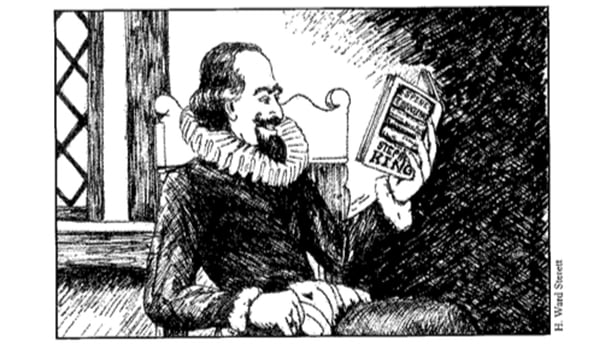

A writer, asked during a literary party what her new novel was about, turned on the questioner with an expression combining irritation, indignation, and pity, and replied, “My novels aren’t about things!” Some time later, this same writer would denounce Stephen King in print for hogging the marketplace and for his alleged role in censoring her work, since his works were widely displayed in bookstores while hers were not.

A publisher, when told that an agreement had been made whereby Barnes & Noble would help to promote, on an annual basis and free of charge, a certain type of generally difficult book, twisted her face into a sneer and proclaimed, “That is not a neutral act!” Not long after, this publisher would be heard singing the praises of an independent bookstore whose manager was known to denounce certain customers as unworthy of his attention.

An editor, queried about his range of interests, replied, “Well, I’m not interested in books per se; I’m more interested in the metaphysics of thought, in the gray areas of language, and particularly in the flow of the cosmic.”

While this third incident is not, like the first two, literally true, the mindset that it illustrates does represent a problem for fiction and for those writers, critics, editors, and academics who seek to advance its cause: the struggle between the elitist, standoffish supporters of a self-consciously literary and often pretentious, boring, and even worthless literature, and those for whom a more accessible and traditional type of book, a story well written and well told, still is something to be nurtured, published, and respected.

Just before Christmas, Ron Rosenbaum of the New York Observer nominated Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire as the best novel of the century, citing its Shakespearean qualities. Some in the literary community will froth at the mouth over this suggestion, convinced that such a choice, personal and unverifiable as it is, should better be accorded to a more worthy work, ideally one selected by a jury of all their best chums and cronies. There are certainly other possible nominees, some more appropriate but others infinitely worse, which are probably the ones many literary types have in mind: something long and difficult, possibly impenetrable and unreadable, such as Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow or Harold Brodkey’s The Runaway Soul. If some jokesters suggested that the latter might better have been titled The Runaway Novel, for its interminable and claustrophobic self-absorption, it is easy to forget that, a century and a half ago, the books of Charles Dickens, almost none of them short, were regarded as both literary and popular and told compelling stories to boot; indeed, it is one reason why such novels as Bleak House and Great Expectations are still read today in sensible college courses as examples of great literature. In today’s publishing world, editors have come to separate the literary from the commercial, and in various eases this makes perfect sense. The hooter alarms should go off, however, every time a self-anointed judge of all that is good lapses into elitist jargon signifying what Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce Indians, back in the 1870’s, might have stated much more simply in his broken English: “Literature good; telling stories bad.”

In an ideal world, literary novels and commercial novels would be equally excellent, albeit in different ways. Many of today’s best commercial novelists are very good at what they do: Stephen King has a marvelous imagination and, in the tradition of Poe and Lovecraft, can channel this into strange and gripping stories told in evocative prose, while a writer such as Patricia Cornwell, with her intricate plots and brisk narrative style, turns out a good effort almost every time, usually showcasing her favorite heroine, Chief Medical Examiner Kay Scarpetta. Yet as successful as these and other commercial authors are, one always has the odd feeling that their publishers are slightly ashamed of them and wish they were instead publishing the latest literary masterpiece, perhaps the new novel by Balzac, book jacket enlivened with a photograph of the author swilling lukewarm beer and pounding on the bar at New York’s White Morse Tavern in the grand tradition of Dylan Thomas or, for the home crowd’s benefit, competing in the Tour de France.

Many of publishing’s elite have lost sight of the fact that the great writers like Balzac and Dickens and George Eliot and Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky, or such modern literary masters as Musil and Hemingway, were not only elegant stylists in total command of vocabulary and syntax but gifted story tellers who possessed the ability to define time, place, and social circumstances and deal with the moral and ethical questions of their era by the way they used language and created characters and situations. They were not neurotic word-meisters fussing obsessively over the id or academic writers composing, time after time, novels about “struggling with the problems of being a writer.” It has been customary to denigrate the so-called European “academic” painters of the late 19th century as lacking in creative ingenuity, but one cannot deny they knew how to paint. The pomposity of some of their canvases—with titles describing pretentiously staged scenes along the lines of Napoleon Inspecting His Troops Before Austerlitz, perhaps, or Roman Centurions Crossing the Alps—may have been ridiculed as passé by the trendy critics of their day, but it is possible to maintain that there was more artistic worth, certainly more of a message, on their canvases than in the dribblings and slashings of Jackson Pollock and Franz Kline, with their New Age titles like Concept Number 41. Yet many of the more academic novelists of today, rather than showing preoccupation with traditional approaches to their art, seem as incapable of telling a convincing story as Pollock would have been of painting a Delacroix or weaving a Navajo rug. Residing in an hermetic world of perpetual grievance, they continue to regard writers who tell stories as old hat and faintly suspicious, possibly unsavory.

Given their subject matter—what little there was of it—Pollock and his cronies usually did not give their works titles like Provincial Governor Gazing at a Bust of St. Dominic, or Virgin With Unmuzzled Bandicoot, but these days, book titles so often sound alike that one might be forgiven for wishing that more writers would do just that. Today’s literary galaxy is not one circle but many interlocking ones, yet too many of its inhabitants share with a certain type of academic nonfiction specialist the elitist and misguided idea that any book widely read must be inferior; it must have been dumbed down, to use Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s celebrated phrase. This attitude carries with it the unmistakable whiff of contempt for others that has too often characterized the cultural elite, the notion that a novel by Brodkey, or even by a more accessible writer such as John Updike, is only for “our crowd,” and not for loathsome bourgeois types such as computer executives, smart-aleck yuppies selling derivatives on Wall Street, or members of the Waiters’ and Bartenders’ Union.

Writers like Philip Roth, the late Joseph Heller, or newcomer Charles Frazier have managed to have it both ways by virtue of sheer talent: to be literary while at the same time telling stories irresistible even to average readers; to create works that are inventive, humorous, even profound; to sell impressive quantities of books and still be nominated for, and win, the highest of literary awards. Recently, writer and former Secretary of the Navy James Webb, in an editorial-page essay in the Wall Street Journal, praised Heller’s Catch-22 as one of the great modern novels, a model of literature and story-telling. Yet there are those in the literary community who grumble that this, too, is illegitimate. Heller and Roth and many other writers like them having sold out to the “establishment,” to Mammon, to corporate entities like Barnes & Noble or some other alleged enemy, all through the fiendish con game of actually being good at telling a story, of doing what once upon a time (back in the days when that phrase was still in use) all genuine writers knew how to do. Inherent in this childishly antagonistic attitude is the tattered Marxist notion that someone cannot have gotten rich, or become successful, due to intellect, talent, and perseverance alone—such a person must have cheated, or stolen, or otherwise taken advantage of someone inferior. How quaint, then, to overhear modern literary types talking up the true meaning of art at cocktail parties while high-mindedly claiming, as if in an episode of Seinfeld, that their books are not really “about anything,” as if that were some grand achievement.

Equally preposterous is that related and informal subspecies of literature consisting of ostentatiously literary, and too often all but incoherent, books about which the intelligentsia pontificate endlessly but which few seem actually to have read. Swollen, hysterically undisciplined novels such as David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest and Norman Mailer’s Harlot’s Ghost are suddenly blessed as works of genius, much as Harold Brodkey was given a cover story in New York magazine proclaiming him “The Genius” before his dreary magnum opus had even appeared. Many publishing elites and other envious writers, if not actively bad-mouthing these works, make vague comments casting doubt upon the books’ alleged elegant qualities. There is no excuse for the incoherence, but one could suggest logical reasons for the failure to read the books themselves: The most relevant is that these books are unreadable, but some of the more cunning members of the chattering classes have caught on to the reality that there is no reason whatever to read one of these books even if everyone else is talking about it. There is an ingenious strategy employed by attendees at philosophers’ conventions or at gatherings such as the annual Potato Chip Snack Food Association Convention: It is always possible to deflect, evade, or fake the answer to any question by replying with a tricky phrase like, “Ah, but what do you mean by that?”; “But is that always possible?”; or, in Nabisco terminology, “Yes, but who’s to say what Olestra really is?” And since, in the halls of postmodernism, there are usually no matters of plot, character, dialogue, or social setting worthy of debate (with the exception of politically correct necessities like typecasting all businessmen, and especially conservative businessmen, as lowlife swine), one is then free to spend hours carping about minutiae, and indeed there are entire symposia devoted to such crucial literary matters. Anyone with the fortitude to attend the Modern Language Association convention will find, on a yearly basis, more than 500 panels, including such can’t-miss offerings as the formal annual meetings of the Slavonic Literary Society and the Association of Melville Scholars and, one fears, the informal annual get-togethers of the League of Hermaphroditic Steinbeck Scholars, the gala reunion of Cameroonian-American Semaphore Poets, and—in odd-numbered years only—the Council of Disabled Comanche Travel Writers Who Are Also Gourmet Chefs.

Yet there are seldom panels—not literary panels, in any case—at which the works of pure storytellers are discussed in serious terms. It is hard to conceive of a symposium for which the program would be announced as: “Social and Cultural Implications: ‘3 May. Bistritz. Left Munich at 8:35 P.M. on 1st May, arriving at Vienna early next morning.'” This, of course, is the opening line of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, one of the most celebrated novels of all time, unfortunately remembered today more for Bela Lugosi’s lurid 1931 film portrayal of the count than for the fact that the book was considered, at the time of its publication in 1897, a tour de force of straightforward storytelling, heavy with history and atmosphere, however peculiar. The newer literary lions, such as the “brat-packers” of the 1980’s, seem to think that telling a story involves little more than the use of entire laundry lists of brand-name consumer items to set a scene and define a social milieu so that, rather than creating memorable people with their own idiosyncrasies, the pictures drawn are of cliched characters wearing Nikes or smoking Marlboros, drinking a certain vodka or reeking of a particular fashionable cologne. Restless and misdirected, they drift from restaurant to nightclub to apartment to bed and back again, possessing (like their authors) little genuine sense of morality or ethics. To be sure. Jay McInerney and Bret Easton Ellis and their cohorts have appeared in public to fulminate about the evils of capitalism, Ronald Reagan, and Newt Gingrich and to air various inane personal grievances, but one wonders how different their outlook on all this would be had Brezhnev or Gorbachev become president of the United States. In the practice of their craft, these literary youngsters—who are no longer so young, although their public displays of pique and noisy tirades in crowded restaurants about bad reviews are adolescent in their whiny self-involvement—show only marginal talents for plot and character. In their arrogance as self-proclaimed social critics, they would not be pleased to hear their work compared with that of Judith Krantz and Danielle Steel, neither of them elegant stylists but both perfectly respectable storytellers.

Popular literature, in both theory and practice, can encompass many different types of novel: thrillers, stories about family life, the business world, entertainment, sports, academe, the cities, the wide-open spaces of the American West. There have been, through the years, a great many writers who have operated in these areas, excellent at their craft even if, in some cases, only up to a point. Mention any one of their names to an ostentatiously “literary” writer and the atmosphere suddenly turns very dark indeed: Suggestions of philistinism, questionable taste, or, worst of all to some, the failure to be hip, hang in the air, unpleasant for everyone within earshot unless the more sensible point out, if they dare, that Sinclair Lewis, F. Scott Fitzgerald, John Steinbeck, Graham Greene (abominable phony though he might have been personally, as Paul Johnson has pointed out), and even such modernists as J.D. Salinger all were good with a story. The later generations that produced such writers as Updike, Joyce Carol Gates, Don DeLillo, and Martin Amis have been well represented by these and others, all of them regarded as literary, but all perfectly capable of telling intriguing stories that illuminate different elements of society and hold the reader’s attention. They might appear on literary panels to discuss the more obscure aspects of their craft but probably not to talk about creating a plot and telling a story. Such mundane matters are too middlebrow for comfort: Better to delve into problems of hermeneutics, semiotics, aesthetics, and, if time permits, everyone has had plenty to drink, and the crowd does not suddenly turn unruly, possibly even prosthetics. And one should never count on seeing younger, less formal, and politically incorrect writers with unusual story material such as Carl Hiassen (too funny and too much about Florida—such an uncultured state) or Sue Grafton (too alphabetical—and where is the opposing view that there is nothing wrong with misspelling something?), Scott Turow (too trial-lawyerish, unless one is looking to sue a Republican), or John Irving (too picky about his children’s education: what nerve!).

In 1927, fantasy and horror writer H.P. Lovecraft wrote a strange novella called The Case of Charles Dexter Ward, in which there are many references to the Necronomicon, a forbidden and sinister ancient volume containing formulae for calling up the dead. At one point, rare book collectors were hunting furiously for available copies, a wonderful example of a fictional invention accepted as fact by the uninitiated, and then passed down from reader to reader as something of historical value. This misunderstanding is innocent enough and even droll in the retelling. By contrast, novelist John Gardner wrote in his book-length critical essay On Moral Fiction of propaganda as a type of writing employing “overemphasis on texture on the one hand and manipulative structure on the other”-an excellent way to describe many of the more overwrought new “literary” efforts. Yet a conformist intellectual community that celebrates, through its propaganda, this kind of undisciplined and unedited writer as a creative genius—and whose editors brag about how impossible these books were to edit—while denigrating mere storytellers as hacks is not so innocent; it is, in fact, one of the least appealing features of modern literary life.

There will always be writers who tell stories and are good enough at it that they succeed in spite of the roadblocks placed in their path by the guardians of all that is good. There remain, still, editors actively looking for good books that tell good stories, although it often seems that there are even more editors hustling after the latest celebrity memoir, or The Reverend Al Sharpton’s Guide to the Lesser Ballets. As for the tricksters, the self-involved faux literati with no plot ideas other than their own angst, they will move through each day with a springy step, serene in the knowledge that they will always be allowed by their chums highly placed in the intellectual community—fellow travelers in the practice of vanity, mutual flattery, and the brown nose—to fake it.

Tolstoy would be appalled.

Leave a Reply