During his debate with Citizen Perot, Vice President Al Gore joined a distinguished list of misinformed public officials when he bashed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff. Senator Reed Smoot and Congressman Willis Hawley “raised tariffs,” Gore said, “and it was one of the principle causes . . . of the Great Depression.” Predictably, the national press jumped with joy. Claiming the “famous tariff lives on in the annals of invincible ignorance,” the Wall Street Journal recalled that Smoot and Hawley “represented a brand of dumb and reactionary Republicanism that consigned the party to also-ran oblivion.” Business Week assailed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff for “triggering the Great Depression and paving the way for World War II.”

In recycling old Smoot-Hawley stories, Gore and the Wall Street Journal demonstrated slavish devotion to the conventional wisdom. But historians know that the conventional wisdom is often wrong, as it is about Smoot-Hawley, and for two generations, the myth-makers have spun a poignant tale of misdeeds and mistakes. In June 1930, the story goes, over the advice of 1,000 economists. President Herbert Hoover signed into law the Smoot-Hawley Tariff, containing the highest protective duties in American history. Smoot-Hawley, they claim, shook the stock market, exacerbated the Great Depression, and provoked foreign protests and retaliation. In succumbing to shortsighted economic nationalism, the United States wrecked the international trading system and paved the way for Nazi political victories and Japanese conquests.

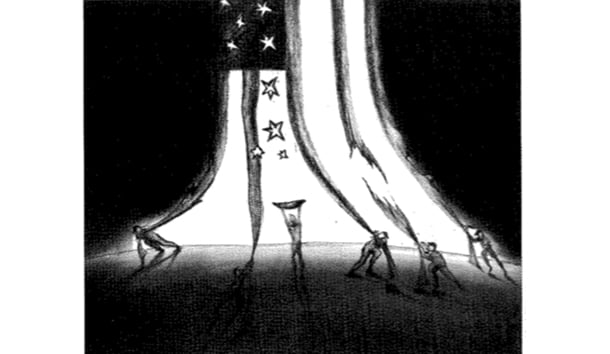

Attacked from all directions, Smoot-Hawley became—like Pearl Harbor, Yalta, and Vietnam—a metaphor for public policy failure. National leaders from Franklin Roosevelt to Ronald Reagan, George Bush, and now Al Gore have invoked the “lessons” of Smoot-Hawley to warn against rising protectionism and impending trade wars, and textbook and editorial writers regularly condemn Smoot-Hawley and preach the perceived virtues of free trade. But this bugbear interpretation of “infamous” Smoot-Hawley rests on a foundation of fantasies and fabrications, not facts. Eager to slay protectionist dragons, politicians, journalists, and scholars have invented and perpetrated myths while blithely ignoring the historical record.

First, the Tariff Act of 1930 did not enact the highest tariff in American history. During the second half of 1930, after enactment of Smoot-Hawley, the average duty on all imports was 13.7 percent. This was certainly no record. From 1821 to 1914—for 94 consecutive years—the average tariff on all imports always exceeded the Smoot-Hawley level. Average duties on all imports peaked not in 1930, but a century earlier in 1830 at 57.32 percent.

To support the pervasive image of resurgent Smoot-Hawley protectionism, many writers focus on a single tariff number—the average duty on dutiable imports in 1932. This figure was indeed 59.1 percent, and it was in fact one of the higher dutiable rates in American history. It was not the highest, however. In 1830 under the Tariff of Abominations, dutiable rates peaked at 61.69 percent.

Like supermarket tabloids headlining the latest exploits of Madonna or Lady Di, writers who magnify a single photo or statistic frequently miss the truly significant story. Congress did not enact this 59.1 percent duty in 1930 as part of the Smoot-Hawley legislation. This duty resulted later, when declining prices and tax increases on commodity imports in 1932 ratcheted up effective tariff levels.

This critical point warrants further explanation. Like previous tariffs, the 1930 act relied extensively on specific duties. Nearly half of Smoot-Hawley imports were taxed at specific rates—meaning at a fixed amount per quantity, like 20 cents per pound. Thus, as prices plunged during the Great Depression, the percentage equivalent of such specific duties soared. A 20-cent duty on an item worth $1.00 effectively becomes a 40-percent duty if the price falls to 50 cents per unit. Had prices remained constant, the U.S. Tariff Commission calculated that the Smoot-Hawley rates on dutiable items would have averaged 41.6 percent—certainly not a prohibitive tariff by historical standards. In fact, in 51 of the 94 years from 1821 to 1914 the average rate on dutiable imports exceeded that amount.

Thus, the two Republican legislators who coauthored the 1930 tariff—Senator Reed Smoot of Utah and Congressman Willis Hawley of Oregon—achieved notoriety because of circumstances beyond their control. Had Congress not approved a tariff bill in 1930, falling Depression-era prices would have ratcheted up existing duties under the 1922 tariff. Eager to discredit Ross Perot in any way possible, it is not difficult to imagine Vice President Gore combing the Library of Congress for a picture of two other obscure congressional leaders: Representative Joseph Fordney (R-MI) and Senator Porter McCumber (R-ND), authors of the 1922 tariff.

Smoot-Hawley bashers usually overlook another key point. The notorious 59.1-percent rate applied only to one-third of total imports in 1932. The 1930 act slightly expanded the free list so that two-thirds (66.8 percent) of U.S. imports, by value, entered duty-free. Smoot-Hawley permitted a larger percentage of imports to enter the United States duty-free than before or after, except in wartime. In 1991, for example, only 35 percent of U.S. imports entered duty-free, about the same percentage as in 1970 or 1890. Perhaps this is the real secret. During extraordinarily difficult economic times. Congress succeeded in writing a tariff schedule that actually increased the share of freely traded imports, while raising rates on some politically sensitive items to pre-World War I levels.

What about the claim that protectionist Smoot-Hawley spooked the New York stock market and contributed to the Great Crash? This is preposterous. President Hoover and Congress completed their work on the tariff in June 1930, nine months after the stock market break. Elementary logic suggests that an event in 1930 cannot cause an event in 1929. Interestingly, the business community did not fear higher protective tariffs. They feared gridlock and uncertainty. The October 1929 stock collapse came after a loose coalition of progressive Republicans and Southern Democrats seized control of the tariff bill, resulting in congressional deadlock. The stock market recovered during the spring of 1930 when President Hoover’s Senate allies succeeded in breaking the stalemate and completing the Smoot-Hawley bill.

Did Smoot-Hawley actually worsen the Depression, as Al Gore claims? Modern economic historians reject the Vice President’s claim. Peter Temin of MIT states that the contradictory argument “fails on both theoretical and historical grounds.” If higher U.S. duties had reduced import access to the U.S. market, dutiable imports should have fallen more rapidly than duty-free imports. They did not. From 1929 to 1931, as the U.S. entered the Depression, imports of dutiable and nondutiable goods both fell by the same amount—33 percent.

To demonstrate that Smoot-Hawley harmed world trade and deepened the Depression, critics must prove that the 1930 tariff provoked substantial foreign retaliation against U.S. exports. Certainly a number of foreign governments did seek to influence the congressional tariff-writing process in 1930 with talk of protests and reprisals. But declassified State Department records, available in the archives to any interested person, contain little evidence of either formal protests or meaningful retaliation. Many textbook writers assert that 34 countries protested Smoot-Hawley. In fact all but three or four such communications were routine. Unable to testify before Congress, foreign businesses and importers simply turned to diplomatic channels to communicate technical concerns to Congress. In 1929-1930, the State Department served as a mailman for foreign interests.

Compelling evidence that foreign governments avoided disruptive retaliation emerges in the State Department’s internal records. Asked to assess foreign reactions to Smoot-Hawley, the State Department solicited information from overseas posts a year after the tariff act took effect. Summarizing responses, the State Department reported: “With the exception of discriminations in France, the extent of outright discriminations against American commerce is very slight.” The official review concluded: “By far the largest number of countries do not discriminate against the commerce of the United States in any way.”

If France was the most flagrant example of discrimination, the problem of foreign retaliation was small indeed. Exports to France fell 54.2 percent from 1929 to 1931, less than the 54.6 percent overall decline in U.S. exports. Exports to Switzerland, another country where citizens marched to protest Smoot- Hawley, fell only 22.4 percent. In Canada, where some retaliation occurred, U.S. exports fell slightly more than average— 58.2 percent. However, exports to other major markets unaffected by higher Smoot-Hawley rates declined even more sharply. U.S. exports to Brazil fell 74 percent, to Colombia 67 percent, and to Venezuela 66 percent. In effect, trade data suggest that a decline in global demand associated with the Depression was far more important an explanation for falling U.S. exports than retaliation against Smoot-Hawley.

Did President Hoover imprudently reject the sound advice of more than 1,000 economists who urged him to veto the tariff act? Many pundits seem to think that the academic economists understood the economic conditions better than elected officials like President Hoover and members of Congress. But the 1,028 economists who appealed to both Congress and President Hoover made no specific reference to provisions of the pending legislation. Their memorial condemned higher tariffs with general economic arguments. They did not seem to recognize that the pending bill contained a flexible provision permitting the President and the Tariff Commission to adjust tariffs in response to changing circumstances. Given the vague nature of the economists’ appeal, both Congress and President Hoover properly spurned the academic theorists.

Did public dissatisfaction with Smoot-Hawley protectionism cost Chairmen Smoot and Hawley their elective offices in 1932? Interpretations of ballot-box fury appeal to doctrinaire free-traders, but they do not conform to the factual record. Home-state newspapers in both Oregon and Utah attributed the defeats of Chairmen Hawley and Smoot to nontariff factors.

Ways and Means Committee Chairman Hawley lost in the May 1932 Oregon Republican primary to a colorful state official. Both the Salem Oregon Statesman and the Portland Oregonian credited the defeat to “local issues.” Obtaining a federal soldier’s hospital for one town in his district, Hawley angered several other localities. Noting that “democracies . . . are ungrateful . . . they are sometimes foolish,” the Portland Oregonian stated that “Mr. Hawley lost many votes that he would have retained had he let the hospital go to the state of Washington.” Both papers also cited the Prohibition controversy. Hawley was a “dry,” his opponent a “wet.” Most of all. Chairman Hawley had served in Congress a quarter century; he did not even return to Oregon for the primary campaign to rebuild his personal ties with voters. In such circumstances, it is not surprising that voters replaced a 68-year-old incumbent with a popular official 20 years younger. Those dissatisfied with Smoot-Hawley, according to the Portland Oregonian, were timber interests concerned about inadequate protection, not about excessive tariff increases.

In Utah, the 1932 Roosevelt landslide toppled Senator Smoot and other Republican candidates, not dissatisfaction with the protective tariff. According to a New York Times correspondent, Smoot was not “discredited, but the victim of a nationwide demand for a ‘new deal.'” In losing, he gained more votes in Utah than either President Hoover or the Republican candidate for governor. Like Hawley, the 70-year-old Smoot fell to an opponent some 20 years younger, who also endorsed protection. In the Utah senate election, both candidates were Mormons. Some Mormons may have voted to bring Smoot home to devote more time to his responsibilities as an Apostle of the Mormon Church.

Was Smoot-Hawley the wrong tariff at the wrong time? Internationalists delight in attributing to Smoot-Hawley the subsequent breakdown in world economic and political relationships, but this line of criticism reflects the notion that the United States had a special responsibility to manage the world economy. In particular, they claim that high American tariffs complicated European efforts to sell goods in the U.S. market and make payments on World War I debts.

But Chairmen Smoot and Hawley, as well as a majority in Congress, had a different definition of their responsibilities in 1930. Their loyalties lay with constituents and voters, not international bankers and bondholders. The immediate concerns of American workers, producers, and farmers took priority over abstract and long-term foreign policy concerns. As Smoot said: “This Government should have no apology to make for reserving America for Americans. That has been our traditional policy ever since the United States became a nation. . . . We will not compromise the independence of this country for the privilege of serving as schoolmaster for the world. In economics as in politics, the policy of this Government is, ‘America first.’ The Republican Party will not stand by and see economic experimenters fritter away our national heritage.”

For over 60 years the citizens have controlled debate, maligning President Hoover for approving Smoot-Hawley. Hoover signed the act because it contained a progressive innovation—a flexible tariff provision permitting the independent Tariff Commission to modify individual rates subject to presidential approval. Hoover was no rigid protectionist, but he and his friend Smoot, and other Republicans, believed that the American standard of living depended on preserving the protective system. “Economically the United States has advanced far ahead of the rest of the world behind a protective tariff barrier,” Smoot observed in 1932. “The major issue . . . is ‘Shall the barrier be removed so that the American people will have to slide back down to the economic level of the rest of the world.'”

If Smoot, Hoover, and other participants could comment on the controversial North American Free Trade Agreement, they might offer an unsettling thought: America’s present economic problems result in significant part from two generations of misplaced trade priorities. They would blame doctrinaire free-traders for dismantling the Smoot-Hawley system while failing to obtain meaningful reciprocal access to major foreign markets for U.S. farm and manufactured products. Hoover would undoubtedly point proudly to his 1932 campaign speeches where he prophesied present difficulties. The end of protection, he said, would bring “disaster” for American workers and farmers as wages and living standards declined. “Grass will grow in streets of a hundred cities, a thousand towns; the weeds will overrun the fields of millions of farms if that protection be taken away.”

To re-stimulate the domestic economy and create high-paying jobs for American workers, Smoot and Hoover would offer the American people far more than a one-sided GATT trade deal from the Uruguay Round. They would counsel Clinton to heed the anxious little people—the workers who made this nation great—instead of the country-club jet-setters determined to make big money moving plants around the world in pursuit of cheap labor.

Leave a Reply