First Man

Produced by Wyck Godfrey, Marty Bowen, Isaac Klausner, and Damien Chazelle

Directed by Damien Chazelle

Screenplay by Josh Singer from the biography by James R. Hansen

Distributed by Universal Pictures

Black 47

Produced by Fastnet Films and the Irish Film Board

Directed by Lance Daly

Screenplay by P. J. Dillon

Distributed by IFC Films

Chuck Yeager, the much-celebrated Air Force test pilot, derisively referred to NASA’s original astronauts as “spam in a can.” He meant that once these extraordinarily brave men were strapped into their modules, they practically had no agency. Their flights and maneuvers were controlled remotely by hundreds of technicians on the ground. It’s well known that the scientists involved with America’s nascent space-flight project, including Wernher von Braun, didn’t want human beings aboard for the ride at all. The politicians involved insisted otherwise, however. They had decided that we had to prove to the Soviets that we could do it. But by 1961, NASA was already late to the contest. Yuri Gagarin had orbited the earth successfully in April of that year. It would take another five years for the Mercury astronauts to achieve space orbit.

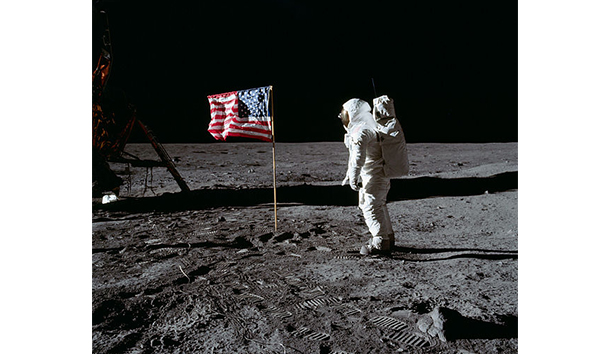

At the time, Neil Armstrong (Ryan Gosling), who was a member of the Mercury mission, took quiet exception to Yeager’s spam remark. He was training arduously for space flight, and when he became the first man to step on the moon’s surface in 1969, he must have thought this accomplishment put paid to Yeager’s sneer, not that he ever boasted about it.

James R. Hansen’s meticulous biography First Man: The Life of Neil A. Armstrong, on which Damien Chazelle based his film, dismisses Yeager’s remark, noting that Armstrong found it at once unfair and uninformed. Oddly, Chazelle, who takes Armstrong’s side in this debate, manages, wittingly or not, to reinforce Yeager’s derision.

To be sure, Chazelle emphasizes that Armstrong and his shipmate, David Scott, not only were among the first Americans to reach space but also managed the tricky challenge of docking with the Agena, an unmanned orbiting space vehicle, thoroughly contradicting Yeager’s remark.

In this sequence and many, many others Chazelle shows us Armstrong in extreme close-up, so close that we can’t see much else beyond him. This is Chazelle’s choice with the other actors also. With the exception of Sergio Leone’s delirious westerns, I can’t recall another film so dominated by close-ups. Even outside the space capsules, Chazelle films his actors in extraordinarily tight focus. They’re so close that other elements you would expect in a biopic are crowded from the frame. In an outdoor barbecue at Armstrong’s home, we see little of his backyard. His lawn, trees, and fence seem to have gone missing. Instead, in shot after shot, we’re presented with little more than Gosling’s clenched face.

The film opens with a close-up of Gosling as Armstrong flying an X-15. The plane is “bouncing off the atmosphere” as Armstrong wrestles with the controls. We see his head whipping from side to side as he tries to bring the plane down. We get brief glimpses of the sky swirling outside but its Armstrong’s face that we keep coming back to. Later, at home, we see him carrying his two-year-old daughter around his house. She’s crying uncontrollably and he’s trying to soothe her. The camera alternates between the infant’s face and Armstrong’s, each in extreme close-up so that we can barely make out the appointments of his home: furniture, appliances, staircase—all outside the frame.

Chazelle’s strategy isn’t difficult to decode. He’s intent on creating a claustrophobic vision of his characters that contrasts ironically with the infinite reaches of space into which they hope to fly. Visually, the astronauts seem to be at once asserting themselves against this limitless expanse and, at the same time, being dominated by it.

The close-up shots also have the effect of disorienting viewers. It’s difficult to get our bearings. I often found myself puzzled by what I was seeing at such close range, especially when planes and later the space capsules are being buffeted by roaring engines and Armstrong finds his craft spinning out of control at a speed that will likely cause him to pass out. The camera stays inside the spaceship while we get fleeting glimpses of what’s going on outside. I found this disconcerting. Why, I wondered, weren’t we allowed to see the space scape outside? Wouldn’t that have added drama to the proceedings?

I suppose Chazelle wanted to put us in the astronaut’s cramped quarters, to feel what he felt. In other words, to experience what it was like to be spam in a can. While I could understand his purpose, he deploys it so relentlessly that I began to think more about his technique than about what it was supposed to convey.

Gosling, who starred in Chazelle’s La La Land, plays Armstrong with an expressionless stone face, which, come to think of it, has become his trademark in film after film. Here it soon becomes a pretentious gimmick. This and his nearly uninflected voice act to divest Armstrong of any trace of humor. His only moment of levity comes in a press conference held just before he will board the Apollo 11 rocket that will take him and his shipmates, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins, to the moon. One of the gathered reporters asks him what he would like to bring with him into space. After a moment, he replies, “More fuel.” Is this a joke? His vocal delivery is so flatly matter-of-fact that it’s impossible to tell with certainty. Armstrong was the astronaut’s astronaut. All business, all the time—even if and when he might have been teasing his audience.

But Chazelle wants us to know Armstrong was not as robotic as he often seemed. To humanize the astronaut, Chazelle dwells on his daughter, Karen, who died of a brain tumor at two years of age. Her death leaves Armstrong visibly distraught, and yet he shows up to work the following day despite being told he should stay home. During Armstrong’s walk on the moon’s surface, Chazelle cuts time and again to images of Karen playing with her father. Then as the moon walk nears its end, we see the astronaut take from a pocket of his space suit a bracelet with the child’s name on it. It’s the kind that hospitals routinely put on newborns to keep them clearly identified. Then, out of Aldrin’s view, Armstrong drops it into a crater and, in yet another close-up, we see through his space helmet, tears running down his cheek. Yes, it’s schmaltz, but well-intentioned schmaltz I suppose. It’s also as far as anyone knows invented. Hansen reports that while other astronauts would leave mementoes on the moon—Aldrin left one of his wife’s earrings—the by-the-book Armstrong did not bring any souvenirs. OK, so the bracelet is a fabrication, meant to convey that in this bottled-up man were wellsprings of unspoken feeling. Still, there’s no gainsaying the bracelet is a gross exercise in sentimentality. It obscures rather than clarifies Armstrong’s nature.

Armstrong was brought up in the Methodist faith but took to identifying himself as a deist from the time he was in junior high school. Both Methodism and deism emphasize deeds over faith. As such they seem to have left their imprint on his character and may well have been the source of his well-known disinterested commitment to doing things correctly and thoroughly, no matter the challenges and risks involved. I know quite a few men such as this, usually engineers and doctors. They’re averse to sentimentalism and self-aggrandizement. These fellows may not make entertaining drinking buddies, but they’re utterly competent and reliable in both daily life and crises.

Armstrong’s detachment was essential to his missions, whether on the ground or in space. His inability to express his emotions was part of what made him so effective as an astronaut. He was certainly not spam in a can. He was the real thing and had what Tom Wolfe famously called “the right stuff.”

Black 47 also has the right stuff. It’s an Irish production, much of it spoken in Gaelic, telling the tale of the Great Hunger in Ireland from 1845 to 1849. Black 47 is the name the Irish gave to this horror in which over a million tenant farmers died miserably.

The film’s first half is a stark and uncompromising portrait of what people had to suffer at the time. The second half becomes a revenge tale in which the protagonist, Martin Feeney (a formidable James Frecheville), a deserter from the British army in Afghanistan, hunts and kills the Anglo-Irish who were complicit in the deaths of his family members. He’s a lone avenger using the soldierly skills he learned fighting for the Brits. He seems nearly as invincible as a cartoon superhero. However satisfying this may be to the Irish filmmakers, it works to weaken the tale’s credibility. Too bad. Otherwise, the film effectively portrays the bleakness of life for the Irish tenant farmers, people who had seen their land and homes and access to education taken away by the upper-class Brits and their toadies among the Anglo-Irish.

What is most memorable in this film is its evocation of a people viciously oppressed by a ruthless, not to say inhuman, overclass, one of whom is a squire tellingly played by Jim Broadbent. This abundantly comfortable fellow remarks with an obscenely self-satisfied chuckle that “this potato business [the famine] has simplified matters considerably. There are those who look forward to the day when a Celtic Irishman is as rare in Ireland as a Red Indian in Manhattan.” Later he protests that he loves Ireland but for the peasants. “They’re all the same, no appreciation of beauty.” To which one of the men forcefully commissioned to capture Feeney observes that “beauty would be held in much higher regard, if it could be eaten.”

The actors are all impressive, but it is Hugo Weaving who stands out. He plays a British soldier forced by circumstances to become a policeman. He is assigned to hunt down Feeney, which he attempts with great reluctance. When serving with the British forces in Afghanistan, Feeney had risked his life to save him. Weaving’s character has sufficient honor to feel obligated to return the favor despite his current orders. Fine actor that he is, Weaving makes you feel the torment of a man torn by conflicting loyalties.

Despite its evident miscalculations as a drama, Black 47 is an honorable and compelling film.

Leave a Reply