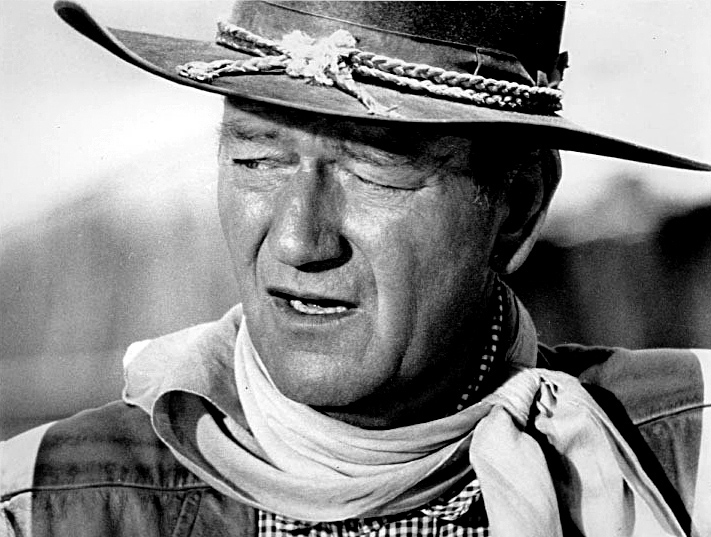

A remark one often hears from the current crop of film critics is that John Wayne might indeed merit the iconographic status conferred on him by tens of millions of ordinary cinemagoers around the world, were it not for the troubling matter of his alleged evasion of military service during World War II—an issue, it would seem, of rather greater consequence to the more ideologically pristine of the professional reviewers than it is to the civilians who actually pay to watch the movies. We can only admire the pundits’ own unstinting patriotism, freedom from self-righteousness, exquisite probity, and universal wisdom—particularly the last, in having an opinion about everything. Wayne himself was by no means as self-assured as many of his detractors, and he winningly remarked that “most acting is forgotten in a day, as any good actor knows.” This was one of his guiding principles, and those who hated him were infuriated not merely by his unparalleled fame, and the quietly disciplined manner in which he went about achieving his uniquely relaxed style, but by the way in which he never aggrandized his profession or believed that a person influences the course of events purely because he happens to “slap on makeup [and] dance around in tights” for a living. He was a standing reproach to the sort of performer who takes himself very seriously indeed and thinks that his work is destined to guide affairs of state.

Wayne was born a century ago, on May 26, 1907, in Winterset, Iowa, where he was baptized as Marion Robert Morrison. The all-important name change came about with his first starring role, in the 1930 movie The Big Trail, and, for all the critical sniggering, seems relatively modest compared with that of certain modern counterparts. (To give just two examples, both of a different political stripe from Wayne, the pleasantly demotic-sounding “Alan Alda” entered the world as Alphonso Joseph D’Abruzzo, while this year’s Best Actress for her performance in The Queen is better known to her loved ones as Ilynea Lydia Mironoff than she is as “Helen Mirren.”)

Wayne had an austere and, it seems reasonable to assume, character-building Midwestern upbringing broadly similar to that of Ronald Reagan, four years his junior. Both men were the product of an only fitfully successful father (an itinerant druggist, in Wayne’s case) and a more obviously formidable mother. Both families eventually migrated to Southern California, where, in a decidedly mixed review of his new surroundings, Wayne recalled,

I had to ride to school on horseback. The horse developed a disease that kept it skinny. We finally had to destroy it, but the nosey biddies of the town called the humane society and accused me, a 7-year-old, of not feeding my horse and watering him.

It was around this time that the boy became “Duke,” because he had an ever-present Airedale terrier of that name; he appears to have been closer to it than to any human relative.

In 1925, Wayne won a football scholarship to the University of Southern California and took a summer job as a scene-shifter and uncredited bit player for nearby Fox Studios. While there, he fell in with the director John Ford, already a veteran of some 60 silent films, turned out at the rate of roughly one per month, whose later product included such screen classics as Young Mr. Lincoln, The Grapes of Wrath, and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. Beginning in 1928, Wayne would appear in more than 20 of Ford’s features, not least among them 1939’s Stagecoach. Here, we’re treated both to a riveting character study and to incomparable action in the form of a protracted Indian attack featuring Yakima Canutt’s celebrated stuntwork. Wayne’s own arrival on the scene as the Ringo Kid remains one of the more arresting entrances in cinema: The audience first sees him framed against the towering flat mesas of Monument Valley, an indelible image that established his quintessentially American, larger-than-life persona that came to assume mythical proportion in such films as The Long Voyage Home and Howard Hawks’s Red River. Of the latter, in which Wayne played a maniacally driven and yet not unsympathetic cattleman named Tom Dunson, Ford remarked, “I never knew the big son of a bitch could act.”

The Searchers (1956) is widely regarded as Wayne’s finest and most complex performance and remains as fresh today as it was more than a half-century ago. It is a continually gripping, sometimes chilling saga, spanning a biblical seven years, which, on one level, works as a straightforward chase story. Wayne’s character, Ethan Edwards, seeks revenge on an Indian named Scar for the kidnap of his young niece. Far from being a mere prototype for the likes of the Death Wish franchise, however, The Searchers offers several beautifully underplayed performances, and Wayne is a revelation as a man given to brooding self-doubt verging on despair, even as he doggedly pursues his quarry. At least one erudite critic has invested the character of Ethan Edwards with classical gravitas and made the connection to Achilles’s fury on the theft of his war prize by Agamemnon. That may be a stretch, but Wayne’s portrayal does have a sense of haunting moral melancholy beneath the obsession that firmly belies the macho stereotype.

Howard Hawks once said of Wayne that his greatest skill lay not so much in his being an all-action hero as its exact opposite. “He [was] observant. He could always find what it had been in an earlier scene that led, logically, to what he was doing just then. Nobody quite grasped the poetry in the flow of film like he did.” It may seem odd to speak of John Wayne and poetry in the same breath, but, in addition to Ethan Edwards, there were to be a number of exquisitely nuanced roles down through the years: His splendidly named Captain Brittles in Ford’s She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, for example, has a tension, a depth, and a poignancy about him that Wayne’s many imitators could only feebly approximate. Part of the appeal came from the vast physical presence of the man (Wayne remains one of the few actors to have mastered the art of lumbering gracefully), but those increasingly craggy Mount Rushmore features were surely only half the story. Time and again, Wayne manages to combine a stoicism and a vulnerability that embody both sides of the classic frontier myth. The films may not always have been realistic, but, by and large, they felt real and they felt right: If they weren’t, strictly speaking, what the West was like, they were what audiences like to think it was like. By showing us the characters’ inner faltering, Wayne offers a more rounded view of the march of our nation’s history than was provided by Clint Eastwood, at least until the latter embarked on his Late Period with 1992’s Unforgiven.

Wayne’s own latter-day output included the breezy self-parody True Grit (1969), in which he played a hard-drinking Western lawman with an eyepatch, and its mildly lackluster sequel, Rooster Cogburn. These were not the career choices of a man abandoned to his own myth. Along the way, there would also be a variety of less distinguished fare, of which 1963’s McLintock!—in which Wayne treats his estranged wife, played by Maureen O’Hara, to a public spanking—represents a leaden nadir, at least from the feminist standpoint. His final role, as the graying cowboy John Bernard Books in The Shootist (1976), took no small degree of courage to carry off: It’s the tale of a onetime gunslinger who attempts to live his last days dying of cancer in peace, but cannot escape his reputation. Although Wayne had bridled at the psychobiographical interpretation that certain of his films evoked, this one accurately reflected his real-life struggle. In 1963, he’d had a tumorous lung removed; he underwent further major surgery in 1978 and died of stomach cancer in June 1979, aged 72.

As Wayne was a more accomplished actor than might be gleaned from his enduring public image—a male Statue of Liberty—so, too, his politics defied easy characterization. It is true that, from time to time, he delivered propaganda tools of considerable handicraft but limited artistic value. In 1968, at the depths of the Vietnam War, Wayne and his son Michael brought to the screen the seven-million-dollar “epic” The Green Berets, a clichéd salute to the Special Forces about which even the Department of Defense had its doubts. In the context of an implausible yarn about the kidnap of a Vietcong general, the film is content to trot out the stock characters: an Irishman named Muldoon; a noble and largely mute Negro; a cynical journalist; and a feisty neighborhood kid with a pet dog. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the reviewers greeted the Waynes’ military-recruitment exercise with restraint, but, for once, the public joined the critical consensus. Although the film eventually recouped its costs, the U.S. box-office take was less than a third of that of True Grit.

In that fast-dawning Age of Aquarius, which transformed the nation into a cultural and political war zone, Wayne represented an almost archaic figure: the unabashed patriot who helped sustain the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals, paid his annual dues to the John Birch Society, and—as if there could be anything worse—supported Barry Goldwater for president. Less well publicized was his extreme personal generosity and espousal of a whole raft of causes not typically associated with the far right. Wayne not only gave his time and money unstintingly but dispensed his favors to those in no position to return them. There is at least one well-equipped children’s ward in a depressed area of Los Angeles that owes its existence to him. Further, he spoke out, 30 years before it became the vogue, on a wide range of environmental and (what would now be called) animal-rights issues. I happen to have spent some of my summers in the early 1970’s on the San Juan Islands, off the coast of Washington state, where Wayne was known to appear regularly on board his boat The Wild Goose. As I remember, he was more than happy to deflate his public image and was frequently to be seen, sans toupee, engaging the locals in a detailed discussion of the islands’ world-renowned but chronically underfunded bird sanctuary. It was later found that he had quietly donated a five-figure sum of money to the enterprise.

Who knows exactly what happened when Wayne was faced with the prospect of military service? At the time of Pearl Harbor, he was 34 years old, with a shaky marriage and four young children to support. He had just completed a breakthrough performance (in Stagecoach), after 12 years of unrewarding B-movies and bit parts. Perhaps Wayne had his current employer, Republic Pictures, lobby to obtain 3-A status (“Deferred for [family] reasons”) on his behalf. Perhaps the studio needed no encouragement to do so. At any rate, the War Department had already made provision to keep the movies alive by all means possible, the theory being that they contributed to national morale by proving that aspects of normal life could be sustained. From 1941 to 1945, Wayne completed 18 pictures, entertained the troops in the Pacific Theater as part of a USO revue, and toured indefatigably in support of the War Bond Drive. He never sought to varnish or obscure his military record, or lack of it, and ruefully acknowledged toward the end of his life that it would continue to be “manna to whole generations” of critics. He was not mistaken in this belief. Meanwhile, it seems reasonable to assume that the infiltration of the real world by other, more deluded movie stars will continue.

From the June 2007 issue of Chronicles.

Leave a Reply