It was in the month of January, the time of frost and snow, that Robert Burns—perhaps the world’s most popular poet—was born in Alloway, Scotland in the year 1759. Being born in that season, Burns seems to have imbibed the mysterious spirit of winter. For no poet captures the quintessence and beauty of winter as Burn’s does in his poetry.

When a boy in school, I remember being rapt in a reverie when I came across this stanza in our school literature text from his, “Winter: A Dirge”—

The sweeping blast, the sky overcast

The joyless winter day

Let others fear, to me more dear

Than all the pride of May:

The tempest’s howl, it soothes my soul,

My griefs it seems to join;

The lifeless trees my Fancy please

Their Fate resembles mine.

For Burns, Winter resembles man’s fallen nature. Robert Burns, in fact, was born during a snowstorm. Winter themes abound in his poetry. Sheltered inside his warm cottage the poet’s thoughts would stray to those less fortunate outside. In, “Up in the Morning Early,”he worries about “The birds chittering in the thorn.” In “A Winter Night,”his compassion extends to the “silly sheep wha bide the brattle O winter war.”

Unique among poets, Burns possessed a tremendous sympathy and empathy with all of creation; extending to the tiniest of creatures—from a mouse whose home he overturned while plowing, to the insect, a louse he spotted on a lady’s bonnet in church. His poetry intuits a transcendent presence speaking through the created world.

His father William Burns served as a gardener to a lord. Before dying, the kindly lord helped William buy a farm. The farm failed. William died when Robert was in his twenties. Burns and his brother, in trying to keep the farm solvent, were forced to labor beyond their strength. This left a permanent mark on Robert’s health.

William Burns valued education. A religious man, he cautioned Robert to lead a good life. But young Burns, mesmerized by the ethereal beauty of women, and overly fond of drink, got himself into trouble. At age 27, and in financial ruin, Robert Burns planned to emigrate to Jamaica.

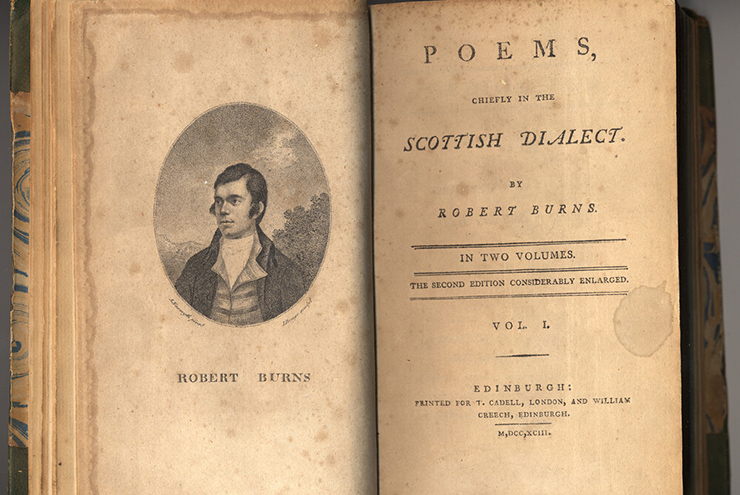

Before parting, he published a book of poetry, Poems Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect funded by subscription in 1786. His fortune changed dramatically with the book’s appearance. A reviewer in Edinburgh wrote of the self-educated poet as a “heaven taught plowman.” Burns became instantly famous, the toast of all Scotland, and its aristocracy fell over themselves inviting the young man to their homes.

Burns, inured by the poverty and tragedy of our human existence, remained unimpressed by the gentry. He viewed worldly success as a great mirage. In a letter to Rev. William Greenfield, he wrote, “when the bubble of fame was at its highest I stood unintoxicated … looking forward, with rueful resolve, to the hastening time when the stroke of envious calumny should dash it to the ground.”

Robert Burns lived in a time of the Enlightenment when a belief in the supratemporal was called into question. Life was being reduced to a material basis of “things seen,” poetry to mere fancy. The poetic eye always looks to the evidence of “things unseen,” which can never be fully grasped and fades from us. “Like the snow falls in the river, A moment white then melts forever.”

There is a longing in Burns for the eternal. Lord Byron summed him up, as, “soaring and groveling, dirt and deity—all mixed up in that one compound of inspired clay!”

In Burns’s time, Adam Smith was writing of the wealth of nations and glories of free trade. Burns described these men of trade as those who, “jostle me on every side as an encumbrance in their way.” His wrote that his faith lay in “a sacred flame” within and in the confidence he could “soar above this little scene of things.”

From his mother Burns learned Scottish ballads. Fully immersed in the folk tradition of Gaelic songs and melodies; Robert Burns holds no high place today among academics. His genius continues to elude them, yet his poetry lives on in spite of them, recited and translated all over the world.

Delancey Ferguson noted in his introduction to Burns’s Letters that if Burns were properly educated in a university, “he would have been taught to despise the folk tradition which has made him immortal.”

I confidently predict that schoolboys will continue to daydream over Burns’s poems. Listening through my windowpane I hear winter still whispering in its own white way and experience a warming of heart, knowing that in such a sullied world as ours, mankind will continue to seek the echoes of their own fallen greatness in this superb poet’s rhymes.

Leave a Reply