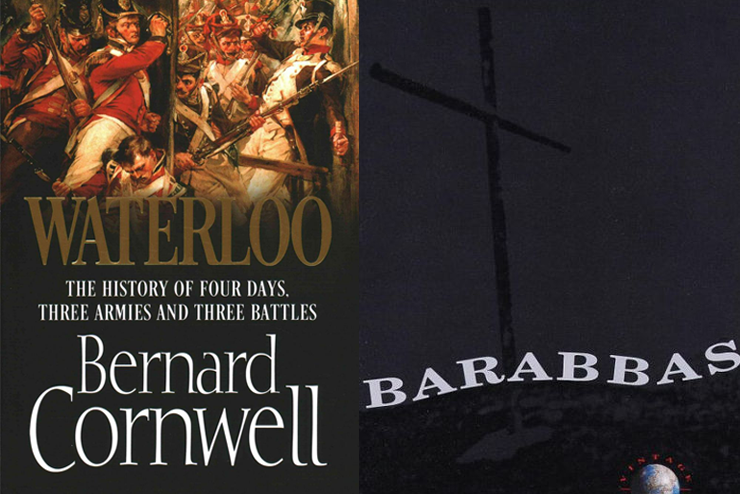

Swedish author Pär Lagerkvist won the Nobel Prize for literature largely on account of his remarkable novel Barabbas (1950). It is like and unlike the best of other such novels based on events surrounding the life of Christ: Henryk Sienkiewicz’s Quo Vadis (1896) and Riccardo Bacchelli’s Lo sguardo di Gesù (The Countenance of Jesus) (1954). All three show that the person and the message of Jesus are revolutionary—not political, but exerting profound and irrefragable influence upon the common life of man.

Lagerkvist wrote his novel in a spare, terse prose for which each word is weighty, as if the novel were a lyric poem, suggesting always far more than it says outright. Like Quo Vadis, Barabbas was made into a Hollywood film. Neither met the hearty approval of the public, probably because there weren’t the expected angelic halos and alleluias, though both are well-acted and have moments of great power. That is especially true of the 1961 film Barabbas, with Anthony Quinn in the title role.

What distinguishes Lagerkvist’s story is that Barabbas does not understand Jesus, is not attracted to his person or his teaching, and does not profess belief in him, until perhaps when he gasps out his last breath, crucified among the Christians whom Nero blamed for the great fire of Rome. Lagerkvist himself was an agnostic, but the novel probes relentlessly what it means that Jesus died for us. For Lagerkvist, that is no pious formula. It is a dread possibility. That is why his “hero” is Barabbas, the one man of whom we can say without any theology that Jesus died in his place.

Barabbas is a taciturn man, a murderer and robber, an unwitting patricide, raised in crime and misery, and doomed to misery wherever he goes. He, like Jesus, will descend into a hell: the Roman copper mines, where he is chained to an Armenian Christian. This man knows things about Jesus even though he has never seen him, while Barabbas cannot understand Jesus even though he has seen him, and has even been an uncertain witness of the resurrection. Barabbas allows the Armenian to scratch on his slave’s disk the Greek anagram for Jesus Christ. When the Roman overseer asks Barabbas whether he believes in this strange crucified God, Barabbas replies that he does not. But, he says, resignedly, “I want to believe.”

That may be what Lagerkvist means to say to modern man, who has lost his faith and reeled back into the beast. Here is the “saint” for our times, a man who cannot understand the first thing about himself, but who is haunted by the Christ who repels him; and yet Jesus died for him, and for him more than for anyone else.

—Anthony Esolen

There are more books about Napoleon and Waterloo than there is name-dropping in Hollywood, and I’m happy to say that I’ve read many of them. Bernard Cornwell’s Waterloo (2014), however, was a revelation. It describes the history of three armies and three battles over four days, and from his descriptions I was able to envision the battlefield as if I had a ringside seat.

There’s another reason for my admiration of this book. European continuity and constancy shines through it, as numerous names of present friends of mine are mentioned. The three that stand out being Generals von Mueffling and Ponsonby, and the winning duke of Wellington. As a youth I dated the offspring of all three: Dini von Mueffling, Caroline Ponsonby, and Jane Wellesley.

Cornwell, who is British, is as neutral an historian as it is possible to be, describing the heroics of both sides in an equal and unbiased manner. He is just as generous to those who did not distinguish themselves on that momentous June day of 1815.

The accepted version of history has it that Napoleon’s defeat was inevitable, whether he won or lost that fateful battle. No, says Cornwell—his strategy was to take on the Prussian, British, Russian, and Austrian armies separately, to divide and conquer as they descended on France. The Russians and Austrians were weeks away, so he split off the Prussians and the Brits and faced them in a northern territory near the sea: Waterloo.

The author gives us countless details about the combatants that bring the fighting men close to the reader. The bravest of the brave, France’s Marshal Ney, had three horses shot out from under him. Despite being known for his boldness and flair, Ney actually lost it for the French by his inactivity, which was unheard of until that day. At the Battle of Quatre Bras he bivouacked instead of charging a retreating Wellington, and when he finally did attack, he did it without infantry support, a rookie mistake committed by the most brilliant of generals.

Just as inexplicable was Wellington’s fortunate inspection of the battlefield a year before, when he noticed a reverse slope and fantasized of placing his “squares” on it to protect them from incoming artillery. One year later to the day, he did it for real.

Astonishingly, the final outcome wasn’t decided until darkness fell and the undefeated Imperial Guard’s last charge was broken. After three major battles, countless skirmishes, and close to 90,000 casualties, it was the 72-year-old, diminutive Marshal Blücher’s charge on Napoleon’s flanks that carried the day. When the Guard finally broke, surrounded by Prussians, Blücher galloped up to Wellington and said, in a mix of German and French, “Mein lieber Kamerad, quelle affaire!” My dear comrade, what a nightmare!

—Taki Theodoracopulos

Leave a Reply