“It is notgood to look too long upon these turning wheels of vicissitude, lest we become giddy.”

–Sir Francis Bacon

It was apt that 1984, the Orwellian Year, should see the reissue of Arthur Koestler’s two-volume autobiog raphy (first published some three dec ades ago) and that the year should also see the appearance of a strange third volume, partly autobiographical, which carries Koestler’s story forward into the mid-1950’s. For Koestler and Orwell shared much in common politically, knew each other very well (and at one point almost became in-laws), and produced a good part of what little political writing of the 1930’s and 1940’s is likely to be of enduring human value. In that sense, Koestler’s story is also the story of the trauma of a whole generation of Europeans, the generation of which Orwell, too, was a part.

Yet Koestler, even more than Orwell, was a child of the massive political and social dislocations of his time, which destroyed so much of the old European culture. The Invisible Writing, by far the better of the two original autobiographical volumes, ends in 1940 with the statement that in Koestler we see a “typical case history of a member of the Central European educated middle classes, born in the first years of our century.” But, as Stephen Spender said, the bitter truth is that Koestler was not typical—unlike three-quarters of the people he knew, he did not end up in either a Nazi Soviet death camp. Instead, the Euro pean whirlwind deposited him on the relatively gentle shores of England, and it was from England, in a language foreign to him, that Koestler first made his cultural mark.

It was in exile, then, from a Europe he feared lost forever that there emerged from Koestler the works for which he will be remembered—above all, Darkness at Noon (1940), the greatest of anti-Communist novels, except for Nineteen Eighty-Four itself. Koestler went on, during the Second World War, to produce some fine political reporting—notably, his attempts to draw attention to the Nazi Holocaust. And after the end of the war came his savage intellectual battles with the French Marxists (Paris had been—and became again—another place of exile): indeed, Koestler could well claim that the furor which followed the publication of Darkness at Noon in France had an important role in keeping the Communists out of power in the elections of 1946.

From the postwar period, too, comes Koestler’s powerful writing in favor of the establishment of a Jewish state. But the culmination of Koestler’s deep intellectual involvement in politics was his active role in setting up the famous Congress of Cultural Freedom in Berlin in 1950, a turning point in defining precisely for all intellectuals just what the issues were, and how terribly high the stakes, in the postwar conflict between the Americans and the Soviet Union. That same period witnessed a second memorable literary effort, to rank with Darkness: Koestler’s role in the writing of The God That Failed. Later, Koestler would reflect on his early battles against totalitarians of all stripes by asserting that he felt the epithet “cold warrior” was an honor second only to the blue tattoo of the concentration-camp victim.

And then: collapse. After the mid 1950’s, political concerns are abandoned in favor of science and (one must say it) pseudoscience; not even the crushing of his native Hungary by Soviet troops in 1956 calls forth any cry. And so, Koestler increasingly forfeited any claim to be a central figure of our time: that is, someone grappling with the most important social, political, and psychological issues of the age. He became instead an author merely of mildly interesting, even diverting books. But those books are not important books, and they will certainly not be read—as Darkness will be—in the next century. What happened here? The clues to the mystery of Arthur Koestler are readily available in the three volumes under review.

“The family tree of the Koestlers starts with my grandfather Leopold and ends with me.” Arthur Koestler came from a family whose rise and fall is in a way typical of what occurred in Mittel-Europa between 1880 and 1930—the creation and then the destruction of a vital, optimistic middle class. Koestler’s paternal grandfather came into Austria-Hungary from Russia, under very mysterious circumstances: Koestler (spelled in a variety of ways) was, in fact, an assumed name. But Leopold married well, and though he never became rich, he had great ambitions in that direction all his life.

Those ambitions were, for a while, fulfilled by Henrik, Koestler’s father—a born businessman and a dreamer fascinated by new scientific inventions (he invested in a mechanical Ietter opener, as well as radioactive soap). Henrik Koestler made (and lost) sever al fortunes, first in Budapest and then in Vienna. He married into another Jewish family whose finances were not quite as big as their ambitions (Koestler’s mother was one of those middle class Viennese matrons analyzed by Freud; she found him “ein ekelhafter Kerl,” however—”a disgusting fellow”). But Henrik Koestler’s various businesses were severely damaged by the outbreak of the First World War, and then they were permanently destroyed by the massive inflation of the early 1920’s, which did permanent damage to the Central European middle classes—and to their outlook.

By this time, Arthur himself was at a technical college: he was destined to be an engineer, a safe and lucrative occupation. But the destruction of his father’s business (and the generally very troubled Austrian economy) made Arthur wary that security and stability were a mirage: “Life was a chaos, and to embark on a reasonable career in the midst of chaos was madness.” And so, with only one semester left before getting his engineering degree, Koestler abandoned his technical training. He entered instead, at the age of 20, upon a long period when he would be tempted by one “total solution” after another to the chaos he perceived around him.

Because he was Jewish, the first ideology which attracted him was Zionism; and it was typical of him that, suddenly “converted” by reading of Arab assaults against Jews in Palestine, he took up with the most uncompromising Zionist organization, headed by Vladimir Jabotinsky (the spiritual mentor of Menachem Begin). Having thrown up engineering, he went off eagerly to a commune in the Jezreel Valley; but he was found wanting by the communards (too individualistic).

After a period of desperate poverty in Haifa and Tel Aviv, he managed almost accidentally to land a job as a Middle Eastern correspondent for the Ullstein Trust, which ran a string of major newspapers in Germany. He had found a calling: and success as a political journalist was followed by success as a popular writer about science as well. By the age of 26, Koestler had emerged as the science editor of the most prestigious newspaper in Germany, while handling foreign affairs for a second Ullstein paper at the same time. He had also joined the Communist Party. The latter came about be cause of his anger at the suffering caused by the Depression, now in full force, and through a deep friendship with a charismatic Communist “mentor.”

All this is covered in Arrow in the Blue, the first autobiographical volume. Some of it, naturally, is fascinating (Koestler’s description of kibbutz life in the mid-1920’s; or his voyage beyond the Arctic Circle in a zeppelin). Worthwhile reading, too, is his detailed analysis of the Communist “conversion” process, and his account of the crippling intellectual impact of its closed system of thought. It is also clear that the dichotomy Koestler establishes as characteristic of his psyche—the search for Utopia (the active life) versus the search for the Universe (the contemplative life)—is absolutely crucial for our understanding of him. Yet Arrow lacks a central focus and theme: we get, rather, a series of disconnected picaresque adventures (some recounted at excessive length).

The problem is compounded by the fact that the protagonist, too, lacks a central focus. Koestler constantly presents analyses of himself to the reader, but they are all intellectual and abstract: his emotional life is almost totally missing. Yet we know (and not least from Koestler himself) that personal relations (especially with women) were of the utmost importance to him: but since he consciously chooses to leave all the women in Arrow (except for his mother) the most shadowy of figures, his relationships with them come and go inexplicably, and so he, too, remains shadowy. It is only when Koestler’s own emotions are actually engaged, then, that he can engage those of his readers. A striking example may be found in his hot defense of his conversion to Communism, on the grounds that it was at least motivated by love of mankind and a desire for justice, things which Koestler doubts that the critics of Communism in the early 1930’s (though not those in the 1950’s) cared much about. Such moments of emotional truth and clarity are all too rare in Arrow, however.

This is not the case with the second autobiographical volume. The Invisible Writing has a clear theme and focus, and great emotional impact. The theme is Koestler’s struggle to remain true to himself under the constant Party pressure for total intellectual conformity; the focus is on the savage storm gathering over Europe: the final collapse of a world. There are as many Koestlerian adventures as before, but they are no longer picaresque: events now hang together with a grim coherence.

Koestler’s induction into the Party was secret and led immediately, and with casual naturalness, to his spying on his employers, the Ullsteins (any one interested in the Hiss case will, I think, find the atmosphere of Koestler’s Berlin in 1931-1932 instructive). Eventually, Koestler was caught and fired—though the Ullsteins, being liberals, never revealed the reasons for his removal. As a result, Koestler be came free to do the thing he now most desired: to make a political pilgrimage to the Soviet Union. His assignment from the Comintern: to write a laudatory account of Russia under the Five Year Plan, under the guise of a travelogue by a “bourgeois but liberal and sympathetic journalist.” While Koestler was in the U.S.S.R., Hitler came to power in Germany. Koestler, in despair, now became a true Party professional, eventually based in Paris; there he worked as a propagandist for the notorious (and charismatic) Willi Muenzenberg-the man who invent ed the idea of the Communist controlled “front” group.

Koestler’s growing doubts about the Party in this period were submerged in his deep need to fight the good fight against Hitler—and also by his feelings of guilt and inferiority over his “tainted” middle-class background (who was he to question the Movement?). But the more he saw of the workings of the Party, the stronger grew his estrangement. It became an impossible dilemma, as more and more of his friends—dedicated Communists—disappeared into the Gulag; and the situation was not helped by the fact that his own literary talent was coming more and more under Party suspicion because of its “bourgeois individualism.”

The final break with the Party came in 1938, during the Spanish Civil War, over the Party’s policy of destroying the Spanish anarchists. Koestler well understood that the anarchists were a force disruptive of discipline in the war against Franco’s “Fascists,” but he had also visited the front as a journalist and seen the anarchists’ uncompromising idealism and populism with his own eyes. The Party, in its drive for total control over the Spanish left and the Loyalist government, now demanded that the anarchists be portrayed as conscious collaborators with Franco; after many lies for the Party, this was one lie at which Koestler finally drew the line. His bitterness here is strikingly parallel to that of Orwell, who also never forgave the Communists and their dupes for what they did to the rest of the Spanish left: like Koestler, Orwell had personally been to Spain, and knew what the truth was. Partly, too, Koestler’s own close brush with death in a Fascist prison had made him suddenly far more sensitive to human and humane values and deeply distrustful of the Party’s implicit policy of “the necessary murder.” Finally, breaking with the Party was made easier for Koestler by the discovery of a different New Jerusalem: after his Spanish adventures, he found that London, with its bourgeois values and ideals of objective truth and the rule of law, suited him far more comfortably than Moscow.

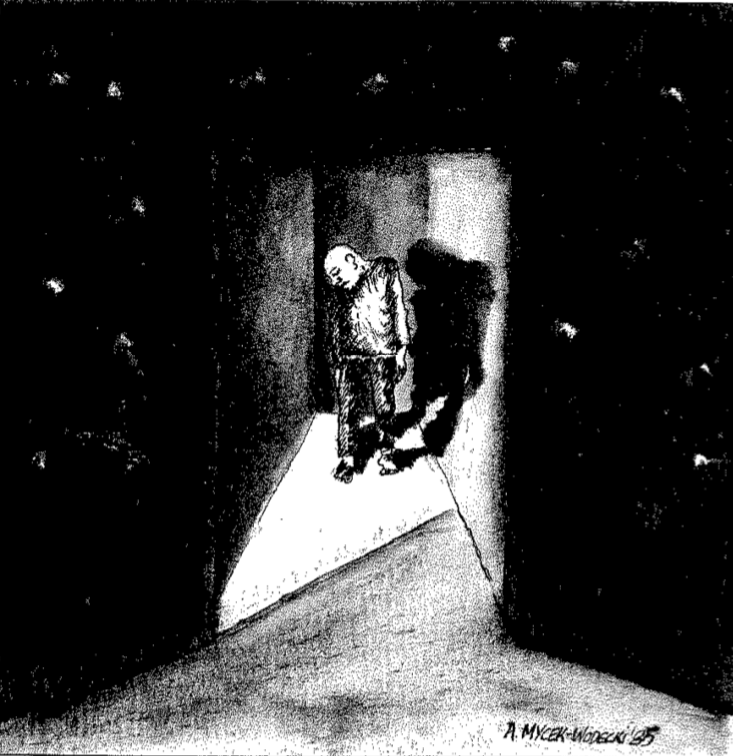

But he hesitated about acting on this insight—and it almost cost him his life. The outbreak of World War II found him editing an anti-Nazi/anti-Stalinist magazine in Paris. Ironically, it was only now that the French government imprisoned him as a subversive, and he was released from a French internment camp with just enough time to finish Darkness at Noon before the Nazis swept all before them in the May catastrophe of 1940. It was only with the greatest difficulty that Koestler, on the run, managed to escape from Nazi hands; and many of his friends did not. He reached safety and sanctuary in England, only via the French Foreign Legion (under an assumed name), and the Casablanca Lisbon route (precisely as in the great Humphrey Bogart-Ingrid Bergman movie; Koestler could have been one of the displaced and despairing denizens of Rick’s Cafe Americain). The last scenes of The Invisible Writing show him going over the proofs of the English translation of Darkness (the German original had been lost when the Nazis took Paris and has never been recovered)—going over the proofs, that is, while himself in solitary confinement in Pentonville Prison, for he had arrived in Britain without a visa: the ultimate refugee. Luckily, his

trusting to chance here worked: he was eventually allowed to stay (he might not have been).

The Invisible Writing is a moving work precisely for the consistency of its powerful emotional commitments (a consistency missing from Arrow in the Blue), and its air of impending, then actual worldwide cataclysm. The great set pieces in this book are among the best things Koestler ever wrote. The story of how in 1933 he betrayed his Russian girlfriend to the KGB, on the slightest of suspicions regarding her loyalty to the State (and the Cause), is a chiller out of Solzhenitsyn; his account of what it meant, emotionally, to be a Communist ought to be read by anyone who wishes to understand the 1930’s and the grip that misplaced idealism can have on people; the narrative of his final “conversion” to a humane, non-Marxist (and mystical) perspective on life while in a Franco prison is absorbing; the story of his desperate search for some sort of sanctuary from the Nazis after the fall of France—his hair-raising flight from an entire continent seemingly lost for ever to one totalitarianism or another—makes all too clear why humane people in that dark time were in such despair. Not that The Invisible Writing is without its faults: with a few exceptions, Koestler’s relationships with women (though of obvious importance to him) are once again portrayed in such a skimpy and abstract manner that the day-to-day personality of this man remains an emotional enigma. But in compensation we have the high moral seriousness with which this book is imbued throughout and a consistently high pitch of authentic politi al emotion. Of the three books under review here, The Invisible Writing is definitely the one to read.

High moral seriousness and high political emotion: these were the crucial elements which seemed, in the I940’s and into the 1950’s, to place Arthur Koestler in the very center of the intellectual life of the West. We return, then, to this question: Why did Koestler turn away from politics and the fight against totalitarianism and spend the last 30 years of his life as a mere popularizer of various scientific and pseudoscientific theories?

His own explanation was simple exhaustion. From the preface to The Trail of the Dinosaur (1955): “I have said all that I have to say on these [political] questions. . . Now the errors are atoned for, the bitter passion has burnt itself out.” But this exhausted man went on to write almost 20 more books, in an age that was hardly without turmoil or undeserving of political and moral commentary. Koestler’s explanation for his behavior can in fact be supplemented with the evidence from the third volume under review, Stranger on the Square. The illuminating information does not come from Koestler’s own last autobiographical fragments, collected in the early parts of Stranger: these are of the usual high literary quality, but they are also (as usual) all too opaque concerning the deep emotional springs of Koestler’s day-to-day personality. Rather, what is of real historical value in Stranger is the primitively written but close-up account of Koestler given in the balance of the book by his longtime mistress and eventual wife Cynthia Jefferies who committed suicide with him in 1983.

George Orwell remarked early on that the key to Koestler was his hedonism: Koestler’s political and personal problem was that he actually thought the goal of life was happiness. Typical Orwell, but the truthfulness of this remark is made vividly clear by Cynthia Jefferies’ contributions to Stranger. What Koestler himself, in the two earlier autobiographical volumes, had referred to vaguely and in an abstract way is now brought forth in overwhelming and eventually depressing detail: Koestler’s compulsive womanizing, his constant drunkenness, his driving desire always to be the center of attention.

Jefferies’ narrative is largely concerned with the years during which Koestler was putting together Arrow in the Blue and The Invisible Writing, and her testimony is all the more impressive coming from someone who is gushingly servile toward Koestler and who, in the end, totally sacrificed her personality to him. What Cynthia Jefferies got in return was a desperately needed infusion of Koestlerian energy and purpose: her relationship with him was no one-way street. Yet any comprehensive attempt to understand Arthur Koestler must deal with the disturbing question of why Koestler, the antitotalitarian, chose in the end to live with someone he so totally dominated and who felt that she was (literally) nothing without him (this is obviously why she joined him in death).

The picture of Koestler that emerges from Stranger on the Square, then, is fascinating, but hardly edifying. In deed, Koestler in the two earlier books had already painted a similar picture of himself, though without the vivid coloring Jefferies is able to provide. It makes sense that such a self-absorbed man, once he had been inveigled into political action, would approach it with the same fierce energy he devoted to his hedonism, and Jefferies gives us a clear view of what it was like to live with Koestler when he was in the grip of a political monomania (in this case, his 1955 campaign to outlaw hanging in Great Britain). But it also makes sense that to shake such a self-absorbed man into political action in the first place would require a cataclysm—or an all-obsessive idea.

And the fact is that after 1955 Koestler faced no such cataclysm, nor (not coincidentally) was he ever again the captive of any such overwhelming political idea. So he returned to what we should probably now see as his first and more natural love—not politics, but the writing of essays popularizing science (compare his early stint as scientific editor of the leading newspaper in Germany). It was natural, too, that as the totalitarian threat eased, so the focus that this threat had given his writing should also disappear, and that he should return to what he had been before 1930 not a cultural hero, but merely a rootless and restless consumer of ideas.

This brings us back full circle. Arthur Koestler—the important Arthur Koestler—was a child of the massive social and political dislocations that wracked Europe early in this century and destroyed the optimistic and vital middle classes to which Koestler be longed. The crisis had pushed Koestler into politics and political writing—and as a sensitive man he had eventually come out fiercely against the totalitarian solution. The crisis had been at its most intense pitch between 1930 and 1950, and during that time it had given Koestler’s life and writing a sharp moral and political focus. But by the mid-1950’s, a certain stability had been restored to Europe; a world was taking firm shape in which Europe (at least west of the Elbe) would be safe from tyranny: all had not been lost. As the crisis passed, and a form of stability was restored, Koestler became free to follow his natural inclinations, which were not (it seems) primarily political.

This, then, is the key to the mystery of Arthur Koestler: his failure to maintain his moral seriousness was the result of the American success in saving Western Europe first from Nazism and then from Communism. With the pressure of tyranny seemingly diffused, Koestler could return to the life he always more truly enjoyed. Stranger on the Square ends in the warm summer of 1956, with an elegiac depiction of Arthur and Cynthia on a carefree gourmet drinking and eating trip by canoe down the Dordogne, through the wine country of southern France.

It is an apt image for Europe, under the protection of NATO, since 1950.

[Arrow in the Blue: The First Volume of an Autobiography: 1905-31, by Arthur Koestler; Stein & Day; New York.]

[The Invisible Writing: The Second Volume of an Autobiography: 1932-40, by Arthur Koestler; Stein & Day; New York.]

[Stranger on the Square, by Arthur and Cynthia Koestler; Random House; New York.]

Leave a Reply