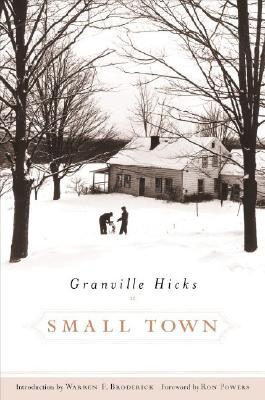

In 1932, Marxist literary critic Granville Hicks and his wife, Dorothy, bought an eight-room farmhouse in Grafton, New York, a rural hamlet ten miles east of Troy, where Hicks taught English to the young engineers at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. For three years, they lived as summer people, aestivating intellectuals, divorced from the community. But when RPI fired Hicks for his Communist Party membership in 1935, he and Dorothy settled into Grafton for good—and for better, as it turned out. Small Town (1946), which Fordham University Press has republished in a handsome edition graced by an informative, sympathetic Introduction by Warren F. Broderick, is Granville Hicks’ account of life in Grafton.

As a boy, Hicks had been something of a sissy, an unhappy New England Unitarian who “did badly in games.” He was high-school valedictorian, but his neighbors “knew that I would be out and away—like all the other bright boys of the towns and the smaller cities of America.” He believed in science, reason, progress: the whole progressive shebang that would give us such marvels of the modern world as Nagasaki, Fox News, and Melissa Etheridge’s test-tube baby. Hicks was well on his way to peripatetic professorhood, a placeless existence in which he could theorize about the proletariat without actually having to meet any of it.

But Grafton interfered. “I wanted roots,” he writes. He and Dorothy found their fixer-upper dreamhouse on a dirt road just outside Grafton. Though Hicks was a “radical intellectual . . . I took the same kind of pleasure in the ownership of property that my mother and father would have taken.” Grafton did not undo Granville’s communism: Hicks didn’t even join the party until he’d been in town for three years. But it refocused his leftism onto the human scale; it reinforced the anti-urban bias of the small-town boy; it taught him things quite beyond the ken of the New Masses.

To the bemusement of his urban friends, Hicks pledged his allegiance to Grafton. And the town accepted him. As Warren Broderick writes, Hicks was “viewed as a personable, harmless, overeducated eccentric” with offbeat political views. No one really cared that he was a communist, for as Hicks writes, in rock-ribbed Republican Grafton, “a communist seemed only slightly more dangerous and slightly more bizarre than a Democrat.”

In time, Granville Hicks became a citizen. Grafton became his town. He was part of its daily life. He donated books that became the core of the Grafton Free Library. He edited a biweekly town newsletter. He helped establish the Grafton Fire Company and Grafton Elementary School. He served as a school-district trustee. He organized harvest dances, for which he also wrote skits. His wife was president of the PTA. He was not slumming or playing at quaintness; he came to belong to Grafton. He writes:

I have learned to like trading in a store where I am known by name and can meet friends and swap gossip. I like knowing the storekeeper not only as a man behind a counter but also as a human being. I feel that I know what I am doing when I vote for or against men I have seen again and again in a hundred different situations, men I have talked with, men I have heard talked about. I like the old-timers, too, though they don’t always like me, and I know they are no fools. Their talk gives the town a past, and sometimes it makes the smart city folks seem shallow. I find it good . . . that I am thrown with many types of men and not merely with intellectuals. In short, I like living in a small town.

Hicks does not pretend to be one of the boys. He never does get used to the interminable talk about car engines. And he accepts the persistence of memory in Grafton: “A man who has lived here thirty or thirty-five years tells me that you can’t become a naturalized citizen in less than a century.” In a passage that still rings true in Interstate-bypassed America, Hicks tells “the outsider bride of a young native, ‘You can say anything you want to about us to anybody in town, but everybody else is somebody else’s cousin.’”

Hicks the erstwhile progressive comes to doubt that rolling icon of the More Abundant Future, the automobile. (“[I]t speeded the decay of the community . . . a disintegrating force.”) The ex-communist searches Grafton in vain for class stratification, finding instead “a basic social equality that results from the smallness of the community and the sense of a common past.” To his satisfaction, Granville Hicks learns that “in the small town you know everybody or nearly everybody, and . . . you know a considerable number of persons in a considerable number of ways.” The man from whom you buy firewood is also a deacon in your church, his son is the point guard on the high-school basketball team on which your son is a bench-warmer, and so on. By contrast, “the city dweller . . . rarely has intimate friends in any social or economic group but that to which he belongs.”

City people, mere orts in the manswarm, cannot really know more than a tiny fraction of the men and women within their daily orbit. The rest must be reduced to a single dimension, so that real, live, complicated, flesh and blood people with distinct, unique histories are shrunk to fit inside the shorthand used by Henry Luce then, Rush Limbaugh now. Liberal. Religious nut. Red state. Blue state. The language dehumanizes the user as well as his quarry.

Hicks, like every man, has his limitations, some rather severe. He is humorless. His prose is serviceable but never sparkling. He is no more accurate a seer than the rest of us: For instance, he is particularly impressed by the unrealized potential in the exciting new field of . . . social studies! Too, a certain biliousness colors his discussion of local politics, though he concedes that “I couldn’t get elected as dogcatcher.” Hicks is no lachrymose sentimentalist. He gets impatient with his neighbors, disturbed by their “intense clannishness, suspicion of outsiders, hostility to new ideas, resistance to change”—which may be necessary defense mechanisms for a small place besieged by school consolidators, draft boards, Taylorized factories, and summer people whose opinions come from the New Yorker.

Yet Hicks would become something of an evangelist for the American small town. His old friends probably sniggered when he declared in a 1946 radio debate:

Whenever I am in New York City, I wonder how people can live without quietness and without clean, fresh air. I wonder, too, how they can stand the pressure of anonymous humanity. I know people as individual human beings. I don’t like the bitter faces and the sharp elbows of the subway.

To Grafton, perhaps Granville Hicks was annoyingly voluble, too articulate by half, resented for his extensive book learning (if privately disparaged for a “lack of common sense”), but, as is said of abrasive or unpopular citizens who sit on boards and organize meetings in all the Graftons of America, he did a lot for the town.

Now and then, Granville Hicks, having jettisoned the juvenile certitude of the ideologue, seems to throw up his hands: “I do not know what should be done to save [Grafton], much less the world.” Oh no, Hicks, you knew. Man, you lived it.

[Small Town, by Granville Hicks (New York: Fordham University Press) 272 pp., $26.00]

Leave a Reply