The Russia-Ukraine War has become a proxy fight between American-led globalism and the alternative: a multipolar world of nation-states free from American hegemony.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has become a test case for the ambitions of the United States and its Western European allies to impose their vision on the world.

Whether called the New World Order, the “rules-based international order,” globalism, or, in the argot of its critics, “globohomo,” the ideals and prestige of the West’s managerial class are implicated by Russia’s resort to old-fashioned force against what it sees as a growing security threat from Ukraine and NATO. Since the New World Order promises peace, prosperity, and the resolution of conflict through nonviolent mechanisms, when a war breaks out, regardless of fault, these claims lose their credibility.

It’s hard to say how much longer the war will go on. Many a war that was supposed to be over by Christmas (as was said of World War I) has lasted many years. Some factors that may portend a longer, more destructive war have been the West’s cheerleading, severe sanctions, transfers of sophisticated weapons, and encouragement of mercenaries to join Ukraine in its fight. Even so, Russia appears slowly, by fits and starts, to be conquering the eastern half of the country. By mid-March, Zelensky had already signaled that some key Russian demands, like forswearing NATO membership, are realities that he will accept. So far, negotiations have not achieved any significant breakthroughs.

While it is hard not to feel some admiration for the Ukrainians and their pluck, it is dizzying to see how fast and how aggressively the West has rallied around Ukraine. Ukrainians, after all, are fighting for ancient, premodern ideas like sovereignty and historic connection to the soil. For the participants, it is an unfortunate war between brothers arising from irreconcilable claims to the same territory. Neither side exemplifies the cosmopolitan values of the New World Order.

Even so, the Russia-Ukraine War has become a proxy fight between American-led globalism and the alternative: a multipolar world of nation-states free from American hegemony. This is why good liberals in the West are making excuses for those who are literally neo-Nazis, and Jewish oligarchs are funding extreme Ukrainian nationalists. While they undoubtedly consider their new allies distasteful, both the oligarchs and the Western politicos see a common enemy in Russia under the rule of Vladimir Putin. The subjective motives of the Ukrainian (or mercenary) combatants are irrelevant to these broader geopolitical and economic concerns of the globalists.

The objective threat to Russia of an expansive Western neoliberalism cannot be denied, especially after NATO powers unleashed themselves on Serbia, Iraq, Syria, and Libya in the preceding decades. Under the spell of a misguided and aggressive idealism, Western leaders are more concerned than ever with “democracy” and the internal affairs of other nations.

In the eyes of these leaders, Putin has reversed Russian progress and driven the nation backwards to its ancient stereotypes. The 19th-century French travel writer Marquis de Custine described Russia as backwards, illiberal, authoritarian, and chauvinistic. If Russia were allowed to be all these things and to succeed on the world stage anyway, the prestige of the Western liberal order would take a serious hit; just as the attempts to impose democracy in the Middle East were discredited by America’s ultimate failure in Afghanistan.

It is ironic that the traditionalism, chauvinism, and illiberalism of Putin’s Russia seem almost identical in character to Ukraine’s far-right nationalist political parties, such as Svoboda and Right Sector. One difference is that Russian nationalism is more ethnically diverse and religiously ecumenical, as it champions harmonious cooperation between ethnic Russians and Tatars, Chechens, Dagestanis, Karelians, and other peoples who make up modern Russia. Like the rhetoric of Russian ultranationalist political figures Aleksandr Dugin and Vladimir Zhirinovsky, Ukrainian ultranationalists express trenchant criticism of the hedonistic materialism that pervades Western Europe, and they offer Ukraine’s more traditional and Christian culture as a worthy example to counter the West’s immoral tendencies.

This is arguably a case of the narcissism of small differences. Being next door to Russia, Ukrainian nationalism is preoccupied with being less Russian and more Western. Thus, after the 2014 Maidan coup, Ukraine passed a language law requiring Ukrainian language in school even though half the country speaks Russian, and the two languages are very similar.

Ukraine’s leadership have also expressed a desire to join NATO and the European Union. The NATO part is obvious; they believe this would vouchsafe protection from Russia. But the desire to be part of the EU system should be more troubling to Ukrainians. Far from enhancing sovereignty, Ukraine’s embrace of the EU model would mean restrictions on protecting domestic industries, mandatory recognition of gay rights, open borders to the Third World, the flight of their most talented professionals, and all the rest.

There is a tragic irony of Ukrainian nationalists pursuing this style of managed democracy, because it empowers an army of unelected bureaucrats, and it privileges the influence of foreign nongovernmental organizations. If Ukraine were to succeed in joining the EU, its membership would ultimately destroy the distinctiveness and character of Ukraine, just as France, Germany, Greece, and Sweden have each found when their national identities were eroded by the EU’s plans for a post-Christian and post-national order.

The distance between popular opinion and the dictates of the EU are even more pronounced among the former Warsaw Pact nations. Far from seeing nationalism as the legacy of the Third Reich, those nations view it as the force that successfully resisted and ultimately obtained independence from the Soviet Union, following the Cold War. For them, nationalism is not expansionist or chauvinistic, but defensive and romantic. But the EU and NATO’s ideologies yield to no one.

Hungary and Poland, now significantly burdened by Ukrainian refugees, have been threatened with the removal of subsidies after the EU’s highest court dismissed their challenge to EU interference with their internal affairs. Radio Free Europe noted, “The EU has been locked in a bitter battle with Poland and Hungary, criticizing the two countries for adopting measures that curb the rights of women, LGBT people, and migrants, and for stifling the freedom of courts, media, academics, and NGOs.”

Western Europeans shed most of their nationalism in the wake of World War II. While the Soviet Union blamed the Third Reich on capitalism, the West pinned the rise of Hitler and the Nazi Party on nationalism. Writing in The Guardian, political scientist Ivan Krastev puts it as follows:

Postwar German democracy was built on the assumption that nationalism leads ineluctably to nazism. As a result, any expression of ethno-nationalism came close to being criminalised—even the national flag at football games was viewed with suspicion. Germany’s radical approach isn’t difficult to understand, given the exceptional nature of the Nazi legacy it had to deal with.

In other words, unlike the Versailles settlement, the antidote to German nationalism after World War II was not a more robust English or French nationalism. Rather, preventing the rise of a similar movement—in Germany or anywhere else—became a major concern for the victorious Allies. This containment would be achieved by rejecting ethno-nationalism altogether. The United States would serve as the Western role model of multiethnic civic patriotism built on democracy and individual rights.

Not only American ideals, but American power contributed to this state of affairs. Then and now, the United States dominated NATO, and the U.S. continues to have troops stationed in Germany. As NATO’s first secretary general, Lord Ismay, famously observed, NATO’s purpose is to “keep the Soviet Union out, the Americans in, and the Germans down.”

The latter part of Ismay’s motto is significant. Not only was West German democracy limited by various laws preventing the legal existence of nationalist parties, but similar restrictions on speech and political action have proliferated throughout Western Europe under the rubric of laws against extremism, hate speech, and Holocaust denial. Beyond these legal restrictions, there is a general taboo on expressions of nationalism in Europe—such as the waving of national flags—as compared to the United States.

These European taboos on nationalism are illustrated by the way the elites circled the wagons to push the technocrat Emmanuel Macron to the fore of France’s presidential contenders, by the passive-aggressive delay of Brexit in the United Kingdom, as well as by the more general and widespread criticism of national populist parties in Hungary and Poland.

The biggest source of friction between the elites and the common people of Europe has arisen from immigration. The treatment of migrants and refugees has become a purity spiral, wherein European leaders have to show their rejection of ethno-nationalism by allowing their countries to be overrun by extremely different and sometimes hostile populations from the Middle East and Africa. The country most preoccupied with such commitments—Germany—embraced this position to an extreme degree under Angela Merkel.

In other words, the entire America-led NATO alliance and the parallel institutions of the EU are all animated by a pervasive fear of ethno-nationalism, which, for modern Europeans, is one step removed from the Nazi regime and its crimes. In this telling, a European nation should no longer be defined by an overarching Christian faith, by a common language, or by the historic peoples who made its culture; rather, it must be remade and subordinated to the demands of economics and broadly liberal values, which provide no privilege to the native-born stock and their wishes.

As in Western capitalism, Soviet Communism tolerated only limited expression of nationalism as an ornament, such as traditional folk dancing or other harmless celebrations. Even this came to an end under Stalin’s rule. The Soviet Union’s more dominant philosophy was dialectical materialism, which counseled progress, economics, and “trusting the science” of scientific socialism.

NATO’s purpose is to “keep the Soviet Union out, the Americans in, and the Germans down.”

While the Soviet Union tried aggressively to subordinate any political expressions of national identity in favor of a more broad-minded commitment to the Communist revolution, the New Soviet Man never really emerged. As its economic system imploded in the late 1980s, the constituent peoples of the Soviet Union returned to their ancient ethnic, linguistic, and religious roots. The latent nationalism of Lithuanians, Georgians, Chechens, and, of course, Ukrainians had much to do with the dissolution of the Soviet Union. This same nationalism also fueled widespread ethnic fighting, including the ethnic cleansing of Russians from the once-multinational empire’s newly independent states, such as Tajikistan and Abkhazia.

When the Soviet Union imploded in 1991, key figures in the West, including President George H. W. Bush and Secretary of State James Baker were more concerned about the dangers of nationalism than those of Communism. The American leaders tried at first to prevent the dissolution of the Soviet Union, which they feared would become what Baker called “Yugoslavia with nukes.” When this failed, Western-funded NGOs, Radio Free Europe, and American and European advisors tried to tamp down movements that were either too nostalgic for Communism or too openly nationalist. (In some cases, the movements were both, as in Russia’s National Bolshevik Party.) In 1996, Time magazine triumphantly reported how the Clinton administration and its experts helped keep Yeltsin in power through sophisticated (and possibly fraudulent) election assistance. The American and NATO prerogative to manage the newly democratic Soviet Union was entirely uncontroversial.

Of course, it’s true that nationalism is not without risks. There was a time when conservatives criticized nationalism as a dangerous artifact of the French Revolution. The European right generally preferred multinational Christian empires as more moderate and just forms of government. A world of competing nationalisms can lead to injustice, extending to the extreme injustices of genocide and ethnic cleansing.

Consider that the Ukrainians and Russians are now fighting over who is the rightful heir of Ukraine and its disputed southeastern region, which the Russians call Novorossiya (“New Russia”). Seventy years ago, Ukrainian and Polish nationalists wielding pitchforks attacked one another’s villages over competing claims to the vaguely defined region between southeastern Poland, southwestern Belarus, and western Ukraine known as the Volhynia. Some 100,000 Poles were killed by the fanatical Ukrainian nationalists under the leadership of Stepan Bandera. This horror show ended only because the ethnic cleansing was more or less completed on both sides.

But nationalism also has a more humane face. As the Russian dissident novelist Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn wrote:

In recent times it has been fashionable to talk of the levelling of nations, of the disappearance of different races in the melting-pot of contemporary civilization. I do not agree with this opinion, but its discussion remains another question. Here it is merely fitting to say that the disappearance of nations would have impoverished us no less than if all men had become alike, with one personality and one face. Nations are the wealth of mankind, its collective personalities; the very least of them wears its own special colors and bears within itself a special facet of divine intention.

While many on the right may prefer a harmonious Christian monarchy, this is no longer part of the terrain of modern political life. The choice is now between robust, competing nationalisms and an American-led globalism that tends towards uniformity, hostility to tradition, and a preoccupation with economic concerns above all else. Thus the populist right chooses nationalism. After all, if nationalism has a mixed track record, so do the utopian anti-nationalist philosophies undergirding leftism, including Communism, socialism, and the American empire’s expansive neoliberal ideology, which repeatedly wages war in order to “make the world safe for democracy.”

As opposed to utopian ideologies, nationalism is grounded in reality, and national identity remains a deep longing within the hearts of modern men. The United States’ and Western Europe’s pretense to speak for the “international community” has generated nationalistic opposition in places such as Brazil and India, both of which abstained from endorsing sanctions against Russia for its invasion of Ukraine. When combined with China—also driven by nationalistic fervor despite its Communist political system—these three nations represent more than a third of the people on earth.

The Ukrainians, while they believe they are fighting for and animated by their own distinctive nationalism, are only being celebrated in the West as foot soldiers for globalism.

Nationalistic countries are on the rise, growing in numbers and economic and military power. Post-war America as the lone hegemon has generated a great deal of international friction and resentment by pursuing economic and diplomatic relations in which subordinate nations have had little say in their national destinies. As a result, much of the nationalism in the Third World now conceives of itself as explicitly anti-American, because the Americanism of the “sole superpower” variety amounts to a global empire.

Instead of leading to the defeat of Russia and its authoritarian model, the Russia-Ukraine War may serve to strengthen and enhance ties between Russia and the various emerging powers, the other so-called BRIC countries (Brazil, India, and China). Varying greatly in their political forms—some democratic, some authoritarian, and some technically Communist—they share a common interest in weakening an increasingly intrusive and demanding United States and European Union. Thus, these emerging powers are rooting for Russia to reduce the West’s prestige.

Domestically, the American right is familiar with the bait-and-switch tactics of the Republican Party. For years, the GOP has promised to fight the culture war and to champion the interests of religious Americans; but when in power, it either does nothing or actively fights to advance leftist goals. There is a reason Donald Trump won the 2016 election.

In similar fashion, Ukraine’s leaders have done a bait and switch upon the Ukrainian people. While President Volodymyr Zelensky and his predecessors have promised an authentic expression of Ukrainian identity and robust national sovereignty, their Western-oriented agenda means that the Ukrainian people will ultimately end up with New World Order homogenization and EU restraints on their national values. The influence and vague commitments of Western powers also have much to do with Ukraine’s current lot: a war in which the costs are chiefly borne by Ukrainians, and which could have been avoided by more diplomatic gestures towards Russia.

One reason Zelensky has become so popular in the West is because he serves the globalist agenda. Zelensky is Jewish—a small ethnic and religious minority in Ukraine—and doesn’t even speak Ukrainian fluently. But Zelensky’s outsider background makes him a symbol for the deracinated, multicultural Ukraine of the future that Europe would prefer. All across the transformed Europe of the future, blood ties to the land and the preferences of the people will count for very little. This Zeitgiest was expressed in The Atlantic by Anne Applebaum, a Polish-American journalist and herself a specimen of the globalist ethos she describes:

The Ukrainians, and especially their president, Volodymyr Zelensky, have made their cause a global one by arguing that they fight for a set of universal ideas—for democracy, yes, but also for a form of civic nationalism, based on patriotism and a respect for the rule of law; for a peaceful Europe, where disputes are resolved by institutions and not warfare; for resistance to dictatorship.

This view of Ukraine’s future is a foreign import, one disconnected from the blood-and-soil nationalism of Lvov and its environs. As Putin said in his pre-war speech on Feb. 21,

Are the Ukrainian people aware that this is how their country is managed? Do they realize that their country has turned not even into a political or economic protectorate but has been reduced to a colony with a puppet regime? The state was privatized. As a result, the government, which designates itself as the ‘power of patriots’ no longer acts in a national capacity and consistently pushes Ukraine towards losing its sovereignty.

Ironically, it was the Soviet Union’s plan for global Communism and a brotherhood of man that ended in tears, ruin, and bloodshed, as well as revitalized nationalism. From this, including our similar ill-fated campaign in Afghanistan, the Western-centered globalist alternative should learn an important lesson: a uniform “rules-based international order” that interferes with self-government everywhere will self-destruct.

Nations and national identities should instead be allowed to flourish. This includes not only the Ukrainian nation, but the Russian one as well. By trying to expand the homogenous global order to the doorstep of Russia, Ukraine now finds itself at war as a proxy for NATO and the EU. In the process, Russia has emerged as a symbolic champion not only of its own nationalism, but of nationalism more generally. The Ukrainians, while they believe they are fighting for and animated by their own distinctive nationalism, are only being celebrated in the West as foot soldiers for globalism.

This tragedy has many dimensions. In addition to the risks to Ukraine’s people, its infrastructure, and to everyone else in the form of nuclear annihilation, the tragedy will continue even if Ukraine somehow emerges victorious. Any such victory will prove to be Pyrrhic. Ukraine’s sought-after independence, once achieved, will be erased by its marriage to the EU and a new invasion of Western grifters, Third World migrants, and the suffocating tentacles of hostile bureaucrats.

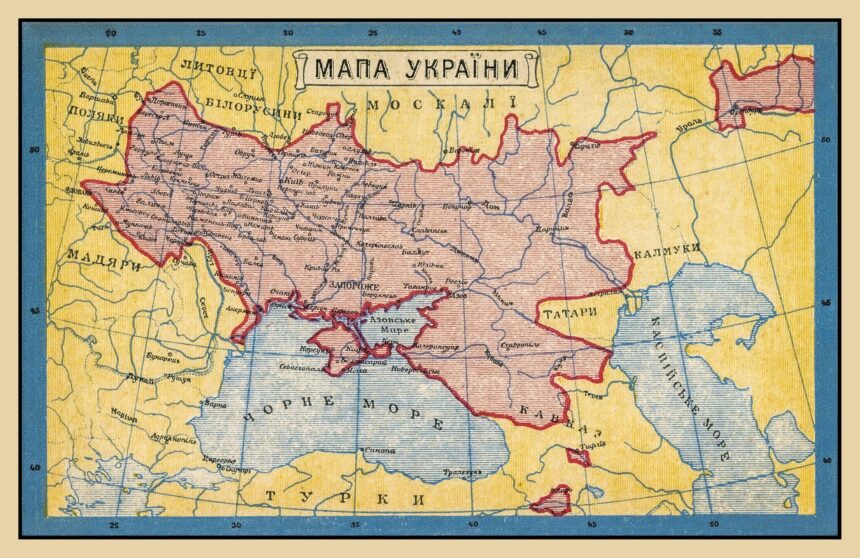

Top image: A map of Ukraine printed in 1919. (Alamy Stock Photo)

Leave a Reply