The burning of Smyrna, the massacre of 100,000 and the deportation of another 160,000 Greeks, happened 100 years ago, in September 1922. Today it is hardly remembered outside Greece, but the destruction of the Greek community in Asia Minor—including the Pontic genocide of Greeks along the Black Sea coast—was the worst act of ethno-religious cleansing in history until that time, affecting some 2 million people. Other Christian ethnic groups—including Assyrians and Armenians—were treated in the same manner and on the same scale in Turkey, in the years just preceding Smyrna’s demise.

The destruction of Smyrna came at the end of the Greco-Turkish war (1919-1922), from which the newly proclaimed Turkish Republic emerged victorious, marking the end of the Greek civilization in Asia Minor, which at its height had given the world the immortal cities of Ephesus, Pergamum, and Philadelphia. The tragedy of Smyrna needs to be known and commemorated, above all by those Westerners who are force-fed the sordid myth of Islamic tolerance.

Smyrna’s devastation was the result of the Greek government’s military campaign, which started in May 1919 with the approval of some Western powers—notably that of the prime minister of Great Britain, David Lloyd George—to capture territory along the Aegean coast and the Sea of Marmara in Asia Minor so as to create a Greater Hellas. This objective reflected the Megali Idea, the irredentist “Great Idea” which had guided the strategy of Greece’s political mainstream in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The Greeks were initially successful, but by 1921, the new, nationalist Turkish army, under the founder of the Turkish Republic, Mustafa Kemal, known as Ataturk, was growing into a formidable fighting force. By mid-1922, the Greek forces were badly overextended, and their lines of supply were increasingly vulnerable. On Aug. 29-31, the Greek army, still 200,000 strong, was completely destroyed at the Battle of Dumlupinar, with half of its men killed or captured and all of its guns and equipment taken by the Turks.

On the eve of its destruction, Smyrna was the wealthiest city in Turkey by far, a bustling port and commercial center. The seafront promenade, next to foreign consulates, boasted hotels modeled after those in Nice, modern offices, and elegant cafes. Yellowing postcards show its main business street, the Rue Franque, with the richly stocked department stores, crowded by the ladies in costumes of the latest fashion. The American consul general, George Horton, remembered a busy social life that included teas, musical afternoons, games of tennis and bridge at one of the four clubs, and soirées in the salons of the wealthy Greeks: “In no city in the world did East and West mingle physically in so spectacular a manner as at Smyrna, while spiritually they always maintained the characteristics of oil and water.”

Smyrna’s prosperity and cultural diversity were an exception to the dreary and brutal Ottoman rule elsewhere. This cosmopolitan oasis was allowed to develop and prosper because it was profitable to a chronically bankrupt Ottoman state, the moribund caliphate based on divinely ordained discrimination against non-Muslims and an unstable coexistence of its many races. Together with the polyglot Constantinople community of Ottoman officials, savvy Greek, Jewish, and Armenian merchants, South Slav dragomans, staffers of Western legations, Albanian bodyguards, Levantine spies of uncertain allegiance, and Young Turk conspirators, the Smyrniots formed a significant part of the urban “Ottoman culture” in the early years of the 20th century. The scene was complex; it had a certain perverse charm, but it was always precariously dependent on the sufferance of the unpredictable and latently murderous Turkish officialdom.

Smyrna’s agony started on Sep. 6, 1922, as the battered remnant of the Greek regular army retreated from Anatolia and passed through the city heading for the ships that would take them home. Their appearance heralded the destruction of the city’s Christian community, which remained convinced, by and large, that Smyrna was too precious a jewel to be wantonly destroyed. Until the very end, many Greeks, Jews, and Armenians assumed that they would manage somehow.

The ensuing disaster was forecast, but Turkish leader Kemal and his commanders deliberately acted not to prevent it, and the governments of Britain, France, Italy, and the United States preferred not to get involved in any way. They sent 21 warships to evacuate their own citizens, with strict orders not to allow anyone else on board.

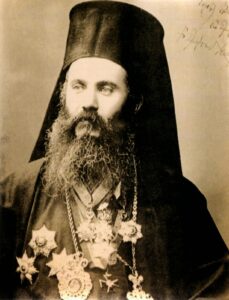

A horrifying massacre followed. It was on par in ferocity with that inflicted on Constantinople after its fall in 1453, but on a greater scale. Sporadic killings of Christians, mostly Armenians, started immediately after the Turkish cavalry entered Smyrna, on Sep. 9. Within days, acts of random violence escalated into mass slaughter. The situation did not just accidentally “get out of hand,” as subsequently claimed by official Turkish sources: rather, Kemal’s top officers deliberately encouraged mass violence. The martyrdom of Greek Orthodox Metropolitan Chrysostomos is illustrative.

Kalafatis, Metropolitan of Smyrna,

1921 (via Wikimedia Commons,

Public domain)

Chrysostomos had remained in Smyrna, refusing evacuation and insisting that it was the duty of the priest to stay with his congregation. On Sep. 10, a Turkish officer and two soldiers took him from the cathedral and delivered him to the Turkish commander, Nureddin Pasha. The officer duly ordered Chrysostomos to leave, perfectly aware that an enraged Muslim mob had gathered outside the building. As the Metropolitan was escorted from the headquarters, the crowd fell upon him, uprooted his eyes, and dragged him by his beard through the streets, beating and kicking him as they went. Sometimes, when he had enough strength, he would raise his right hand in an effort to bless his persecutors, saying “Father, forgive them.” A Turk, furious at this gesture, severed with his sword the Metropolitan’s hand. The holy man fell and was hacked into pieces by the mob.

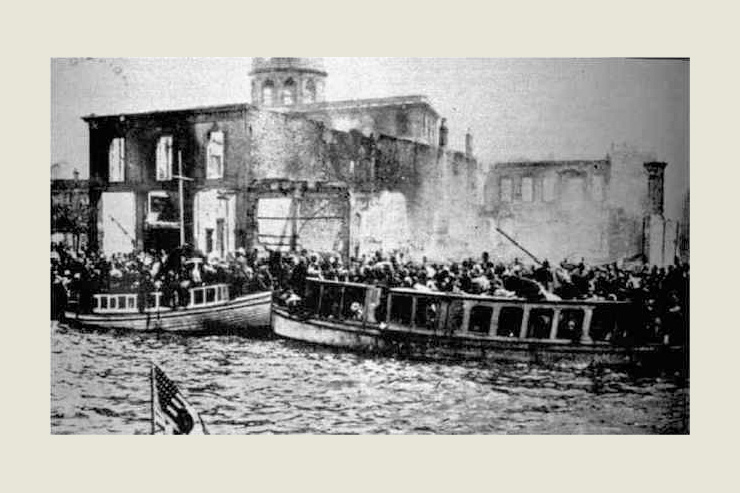

The carnage culminated in the burning of Smyrna. The conflagration started on Sep. 13, after the Turks put the Armenian quarter to torch, and it spread to engulf the entire city. The remaining inhabitants and recently arrived refugees were trapped at the seafront, where there was no escaping the flames on one side or Turkish bayonets on the other. All throughout the devastation, British, American, Italian, and French warships were anchored in Smyrna’s harbor. Ordered to maintain neutrality, they would do nothing for the desperate Christians along the seafront. As Nicholas Gage recorded in his Greek Fire,

The pitiful throng—huddled together, sometimes screaming for help but mostly waiting in a silent panic beyond hope—didn’t budge for days. Typhoid reduced their numbers, and there was no way to dispose of the dead. Occasionally, a person would swim from the dock to one of the anchored ships and tried to climb the ropes and chains, only to be driven off. On the American battleships, the musicians on board were ordered to play as loudly as they could to drown out the screams of the pleading swimmers. The English poured boiling water down on the unfortunates who reached their vessel. The harbor was so clogged with corpses that the officers of the foreign battleships were often late to their dinner appointments because bodies would get tangled in the propellers of their launches.

That was the end of Christianity in Asia Minor. It was a catastrophe barely acknowledged in the Europe of that time, which was obsessed by the effects of hyperinflation in Germany and by the French-Belgian occupation of the Ruhr.

The tragedy of Christian communities under Turkish rule, as former British Prime Minister William Gladstone precisely diagnosed it, was not “a question of Mohammedanism simply, but of Mohammedanism compounded with the peculiar character of a race.” It is therefore not surprising that the persecution of Christians culminated in their final expulsion from the newly founded secular Turkish Republic under Kemal, the man who also abolished the caliphate, separated the mosque and state, and banned veils and fezes. Of course, the fact that this massive feat of ethnic and religious cleansing was carried out under the banner of modern Turkish nationalism, rather than Ottoman imperialism or Islamic intolerance, mattered but little to the victims. The end result was the same: churches were demolished or converted into mosques, and communities that used to worship in them were dispersed or dead.

The prior century of Ottoman rule and the first years of the Turkish Republic witnessed a thorough and tragic destruction of the Christian communities that had resided in the Middle East, Asia Minor, the Caucasus, and the Balkans. Almost the entire Greek population on the island of Chios—tens of thousands of people—was massacred or enslaved in 1822, as immortalized by Eugene Delacroix. The following year, the slaughter at Missolonghi resulted in 8,750 dead. In 1850, thousands of Assyrians were killed in the province of Mosul, and in 1860, over 12,000 Christians were put to death by the sword in Lebanon. The Bulgarian atrocities of 1876 left 14,700 dead. Periodic slaughters of Armenians took place in Bayazid (1877), Alashgurd (1879), Sasun (1894), Constantinople (1896), Adana (1909), and Armenia (1895–1896), claiming a total of 200,000 lives; but these were merely dress rehearsals for the horrors of 1915-16, when the Turks created an artificial famine that killed over 100,000 Christians, mostly Maronites, in Lebanon and Syria.

Historic Muslim tolerance of Christianity and Christians is a myth. The most devious upholders of that myth are Western liberals who have no faith (except in their own self-righteousness) and who have zero tolerance for persecution and discrimination—sexual, racial, religious, etc.—but with one exception: when Christians are the victims. Islam’s Western apologists keep quiet about Smyrna, for now. Perhaps one day they will write about what happened there in September 1922, but only to explain that the Christians had it coming all along and that in the end, it was all for the best.

Top image: Smyrna citizens trying to reach the Allied ships during the Smyrna massacres, 1922 (Benaki Museum / via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Leave a Reply