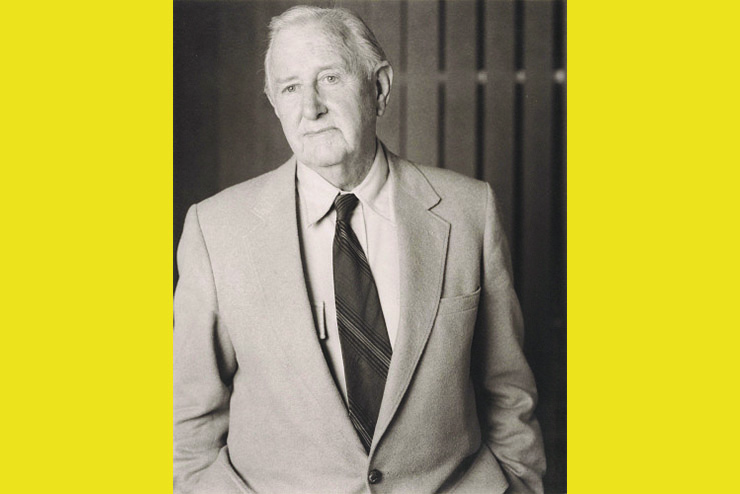

C. Vann Woodward, America’s leading Post-Reconstruction historian, both loved and loathed the South.

C. Vann Woodward: America’s Historian

by James C. Cobb

University of North Carolina Press

504 pp., $37.50

When Henry Ford notoriously proclaimed that “History is bunk,” he expressed a view that was and still is quintessentially American. For the maker of the Model T, the only history that matters is the history we make in the present, as if something could be made out of nothing. Contra Mr. Ford, the history we hope to make in the present is inevitably shaped, if not altogether determined, by the past. The role of the historian is not simply to uncover the truth about the past but to tell his story in a way that will make the past somehow “useful” to us in the present. Thus his loyalties are always, to some extent, divided loyalties.

The problem, of course, is that no matter how elusive the truth of the past may be, the historian—if he is honorable—must not willfully falsify the evidence of the historical record or distort its significance. He must strike a balance that is almost impossible to achieve, especially when he is also driven by a zeal for moral or political reform. In this extensive study of the life and work of Comer Vann Woodward, University of Georgia professor James Cobb admirably assesses the loyalties of one of the most influential historians of the 20th century, whose best-known books explored the rise of the New South and the emergence of the Jim Crow regime. Woodward’s historiography, while to some extent superceded by subsequent research and flawed by a “presentism” that sometimes blinded him to realities that did not serve his own liberal political aims, remains a valuable contribution to our understanding of both Southern and American history in the post-Reconstruction era.

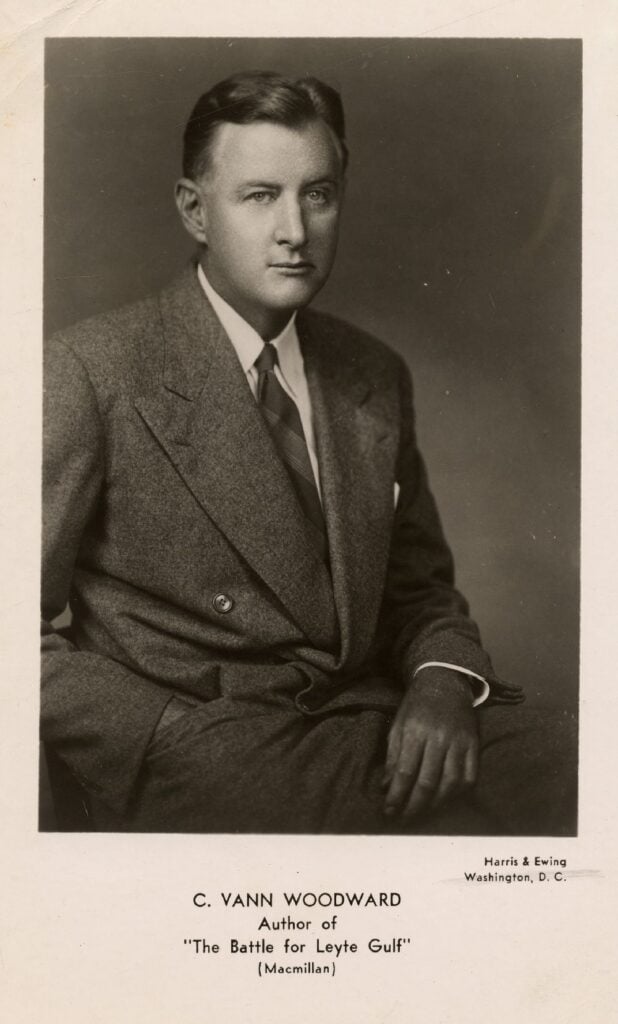

Born in Arkansas in 1908, Woodward came from a family deeply rooted in Southern Methodism and Confederate pride. His paternal grandfather had been a circuit-riding preacher in Tennessee, while his grandfather on the distaff side (the Vanns) served four years in the Confederate Army, later becoming an agricultural merchant and substantial landowner in the Delta region of northeast Arkansas. His own father was a school superintendent who encouraged in his son a love of books and learning.

Indeed, the young Woodward was a prodigy who, by the age of 14, was already reading his way through the novels of Henry James. For years to come he would aspire to write fiction, and undoubtedly the narrative skill he brought to his historical work owed a great deal to his study of James and other novelists he admired, such as Thomas Wolfe.

Leaving Emory University with a B.A. in philosophy in 1930, Woodward resisted the prospect of an academic career, yet began work on a master’s degree in public law at Columbia because he had managed to secure a Rosenwald scholarship and was persuaded that he could manage the necessary coursework while exploring more compelling literary and political interests.

Woodward’s politics had been decidedly left-liberal during his undergraduate years, and at Columbia he became increasingly interested in the Populist Party, which had emerged in Georgia in 1892 from the old Farmers Alliance. That interest led to his master’s thesis on J. Thomas Heflin, the vehemently pro-segregationist U.S. Senator from Alabama. Heflin was not formally affiliated with the Populists, but he leaned left on labor issues, and was known as “Cotton Tom” for his efforts to obtain more favorable prices on the sale of cotton.

His work on that thesis inspired Woodward to begin a book-length study of Southern populist demagogues, which would have included portraits of Louisiana Governor Huey Long, South Carolina Governor Ben Tillman, Mississippi Governor James Vardaman, and Georgia Senator Thomas E. Watson, among others. But Woodward became so absorbed in Watson, the Georgia populist and newspaper editor, that the envisioned book instead became an exclusive study of the man who had been the founder of the Populists and the most articulate promoter of their political goals.

In his early years, Watson distinguished himself by encouraging political cooperation between white and black farmers against the Democrats. The Democrats of the late 19th century represented a powerful coalition of large landowners and industrial interests. They had dominated Southern politics since the Compromise of 1877, which settled the disputed presidential election of the year prior in favor of the Republican candidate Rutherford B. Hayes, but also demilitarized the South following the Civil War and granted other concessions to the Democrats.

There is little doubt that Woodward harbored an animus against the Redeemers, a coalition of ex-Confederate leaders and a rising class of Southern industrialists, mostly involved in the railroad industry, who effectively ensured the dominance of the Democratic Party in the former slave states. The Redeemers emerged out of the disputed 1876 presidential election, which resulted in the confirmation of Republican Rutherford B. Hayes but guaranteed that the Southern states would be granted home rule—a compromise that effectively brought the Reconstruction regime in the South to an end. Woodward’s hostility toward the Redeemers would become increasingly evident in the major works published later in the 1930s, and stemmed in part from his study of Watson.

With his research on Watson already underway, Woodward entered the Ph.D. program at the University of North Carolina in the fall of 1934—yet was still loathe to commit himself fully to that “cursed degree” and an academic career. But UNC proved to be the most exciting academic environment he had encountered. There he found mentors such as Howard Odom, Rupert Vance, and Howard K. Beale—scholars whose approach to the study of the South was influenced by social science, and especially the school of thought associated with historian Charles Beard and his landmark 1913 political history, An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States.

In those years, Southern historians were still dominated by the “militant” advocacy of the Southern Historical Society and its defense of the “Old South-Lost Cause” legacy. According to the arguments advanced by Vance and Beale (who had published a major work on Reconstruction), the Lost Cause historiography had effectively suffocated any revisionist work that might challenge, in Cobb’s words, “a single, broadly encompassing historical creed, which allowed of no piecemeal adoption but must be swallowed whole and undifferentiated, as if at a single gulp.” What Beale, Vance, and, later, Woodward challenged, was above all the notion that the Reconstruction’s troubles grew out of a noxious brew stirred up by “Carpetbaggers, Scalawags, and their ignorant black pawns….” For Beale, ignorant blacks were mere pawns. But so too were Carpetbaggers and Scalawags, who served as tools of Northern industrial and banking interests—or so he argued in The Critical Year: A Study of Andrew Johnson and Reconstruction (1930)—intent on economic colonization of the South.

This view might not, in itself, have been objectionable to at least some of the orthodox purveyors of the Lost Cause creed. However, it also called into question the role of the Redeemers as the anointed saviors of the Southern way of life and the subsequent rise of the segregated New South, long celebrated by the old school as evidence of a heroic Southern response to northern domination. The Chapel Hill revisionists were critical of the segregation regime, not simply due to its injustice, but because in their view it reinforced the continuing economic exploitation of poor blacks and whites.

In Tom Watson: Agrarian Rebel (1938), Woodward built upon this typical progressivist argument, extolling Watson’s Jeffersonian anti-capitalism and his efforts to build a party of resistance against capitalist colonization by placing black and white farmers on an equal footing—efforts which included denunciations of lynch laws, a position he later reversed. As Cobb convincingly argues, Woodward considered Watson a man whose distaste for capitalism matched his own. He was prepared to sidestep Watson’s later turn toward an often vicious race-baiting rhetoric not far removed from that of demagogues like Ben Tillman in South Carolina.

Woodward’s willingness to glorify Watson as a champion of racial harmony rested in part on rather thin evidence—primarily his account of a black minister, H. S. Doyle, who supported Watson’s 1892 campaign for reelection to Congress, making a number of speeches on his behalf. This would not be the last time that Woodward would be guilty of exaggerating the significance of meager evidence. And while most of the reviewers of Tom Watson praised the book, some took him to task.

Among these, the Nashville Agrarian Frank L. Owsley published a major if controversial work on Southern culture, Plain Folk of the Old South (1949). In Owsley’s take on Watson, the Georgia populist’s later politics were not a break with his earlier phase (as Woodward suggested) but “were logically and psychologically identified with his populism.” What had always been paramount for Watson, he asserted, was promoting the populist agenda, not “bi-racialism.”

Owsley, like the Chapel Hill historians, was himself something of a Beardian, but one who drew different conclusions from the historical evidence. Unlike Woodward, Owsley and the Nashville group, while suspicious of capitalism, did not view the

early populists favorably. Indeed, they tended to see the leftist populist ideology, one that prioritized egalitarian class struggle over a cultural unity that transcended class, as an alien import in Southern politics.

1877-1913 by C. Vann

Woodward (LSU Press,

1981)

Although Woodward’s next book, Origins of the New South 1877-1913, was not published until 1951, Woodward spent most of the ’40s working on it. It is without question his most important work, if not his best known. In many respects it was a tour de force that drew upon the work of his Chapel Hill forerunners but infused their perspective with arguments that were, at times, strikingly original. At its heart this massive work presents a fairly simple argument: The narrative that had dominated the work of Southern (and some Northern) historians since the late 19th century had lionized the Redeemers as the saviors of the South, portraying them as principled men who had to a significant extent restored the antebellum order and led the resistance against Northern efforts to colonize the South. Woodward, with some success and great detail, showed how the old narrative was more myth than reality.

In Woodward’s telling, only a handful of the Redeemers were “Bourbons”—that is, gentlemen of the old planter class. Most, instead, rose out of the middle class. More often than not they worked as merchants, lawyers, celebrated generals, and railroad magnates closely tied to Northern finance and enriched by that alliance. Those few who did hail from the old planter class aligned themselves with the rising capitalists and industrialists associated with the New South movement.

Whether wittingly or not, the remnant of true Bourbons were not infrequently used by New South ideologues like Henry Grady to “camouflage” the South’s economic and cultural transformation. In this view even the “Lost Cause” movement, which outwardly celebrated the war’s Southern heroes and Old South values, was in fact an exercise in romantic nostalgia, perfectly suited to mollify the millions of Southerners of every class whose hostility toward the Northern conqueror would have otherwise made the New South agenda more difficult to achieve. As this economic upheaval gained steam, those who suffered most were blacks and the agricultural classes, crushed under the weight of disproportionate tax burdens that drove them off their land (if they possessed any) and left them at the mercy of a “crop-lien” system that drove them further into an endless cycle of dependency and poverty. Woodward notes that “the new evil system [crop-lien] may have worked more permanent injury to the South than the ancient evil [of slavery].”

While Cobb clearly admires Woodward’s accomplishment in Origins, his assessment is not without some justified criticism. For instance, he argues that Woodward was excessively harsh in his critique of the Redeemers, suggesting that “he took too little account of the decidedly unfavorable circumstances they inherited,” circumstances that included the scarcity of indigenous capital (which gave rise to the crop-lien system) or the “restrictions on the nature and scope of postbellum industrial development.”

However, in this context, Cobb ignores the reflections of Woodward’s first biographer, John Herbert Roper, who had noted that Origins is flawed by its author’s unwillingness “to give serious consideration to the possibility that large numbers of intelligent and honorable people actually believed, and believed intensely, in the values encompassed as the Lost Cause.” Or as M. E. Bradford argued some years later, Woodward, in his eagerness to reduce the Lost Cause—and, indeed, the Old South itself—to a rhetorical invention of New South propagandists, goes “too far in denying real continuity [to] Southern piety.”

Bradford, whom Cobb never cites, suggests that this deficiency in Woodward’s perspective may have been by “tactical” design. If so, this would be an instance of Woodward’s not infrequent “presentism,” since with one eye on the progress of the Civil Rights movement in 1951, he understood that if the “solid South” that arose in the aftermath of Reconstruction could be understood as merely an enabling myth, it could be more easily set aside in favor of progressive policies that would bring about a second Reconstruction.

Jim Crow by C. Vann

Woodward (Oxford

University Press, 2001)

Cobb is also sharply critical of at least one of the key arguments in Woodward’s most controversial and most well-known book: The Strange Career of Jim Crow (1955). Here Woodward argued against the common assumption that the Jim Crow regime began, at least unofficially, almost immediately after Reconstruction. His central thesis is that segregation was not a significant factor prior to the mid 1880s, and only became fully formalized in the 1890s and thereafter.

To some extent this is simply a statement of fact. But Woodward went further in suggesting that Southern race relations for almost a quarter of a century after the war were for the most part amicable and largely integrated. In this view, Jim Crow was not an inevitable development of the Compromise of 1877, which ended Reconstruction. Rather, the emergence of segregation statutes arose from political compromises that might have otherwise been avoided. If the segregation regime could be shown to be a highly contingent product of political compromise, and not a primordial fixture of Southern consciousness, then the shapers of Southern opinion might begin to contemplate the possibility that Jim Crow could be consigned to the trash heap.

Woodward was all too eager to make this case because, even as he was preparing Strange Career for publication, he became deeply involved in the events leading up to 1954’s Brown v. Board of Education decision. Consulted by Justice Thurgood Marshall and encouraged by the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund, he was persuaded in 1953 to write a working report that would provide historical context for the contention that the Fourteenth Amendment might be understood as a basis for abolishing segregation.

As Cobb forcefully argues, this degree of involvement in the pressing issues of the day, and his own liberal inclinations (at least on racial issues), inclined Woodward to a presentism that pushed him to ignore too much in his arrangement of the evidence in Strange Career. More generally, he overstated his case. As Cobb notes, to support his claim that the mixing of the races was common after the war, Woodward draws on a paucity of sources and overlooks some clear instances in which de facto segregation was practiced as early as 1866. His own professional peers were quick to dispute his evidence. Woodward published three subsequent editions of the book in which he sometimes ceded ground or inserted revisions in his original argument. This is not to say that the argument was entirely without merit. But it remains a much-debated text.

Woodward was a man of divided loyalties on two levels. As a historian, he divided his loyalty between the historical facts, on the one hand, and his political aspirations on the other. To his credit, he recognized his presentism and made perfunctory efforts to contain it. On a more personal level, he was divided as a Southerner. Though there was much in the Southern past that he deplored, there was also much that he admired. Like Tom Watson (himself descended from a planter family) he revered men like Robert Toombs and Charles Colcock Jones, both planters and loyal Confederates but also trenchant critics of the North’s capitalist order, as well as Robert L. Dabney and his brilliant and scathing postbellum defense of the Lost Cause. More importanly, Woodward extolled the South’s literary culture, particularly the novels of the aforementioned Thomas Wolfe, as well as those of William Faulkner. He corresponded cordially with Agrarian Donald Davidson, and was a longtime friend of the Agrarian poet Robert Penn Warren.

Beneath Woodward’s liberalism, one detects a current of conservatism that grew more pronounced with age. Cobb devotes a chapter to Woodward’s conservative turn, exploring his increasingly vocal opposition to some of the unfortunate manifestations of the civil rights movement, the rise of black separatism, and, as expressed privately, his growing “boredom over Negro rights.” “Twenty-four hours a day … gabble, gabble, yak-yak. Integration, separation, autonomy, black history, black studies, black math, black magic,” he wrote.

Similarly, Woodward found himself at odds with campus feminists’ increasingly strident demands at Yale, where he taught from 1961 to 1977, and elsewhere. Cobb cites several examples of Woodward’s apparent right turn toward the end of his professorial career. However, he unconvincingly suggests that rather than exposing any deeply rooted conservatism, these examples were evidence of a liberalism under siege by an ever more radicalized academe.

Nonetheless, Cobb deserves congratulations for a meticulous and even-handed biography, magisterial in its exploration of one our most celebrated historians. Woodward deserves the title “America’s historian” far more than his oft-lauded peer Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., whose work was manifestly inferior.

Leave a Reply