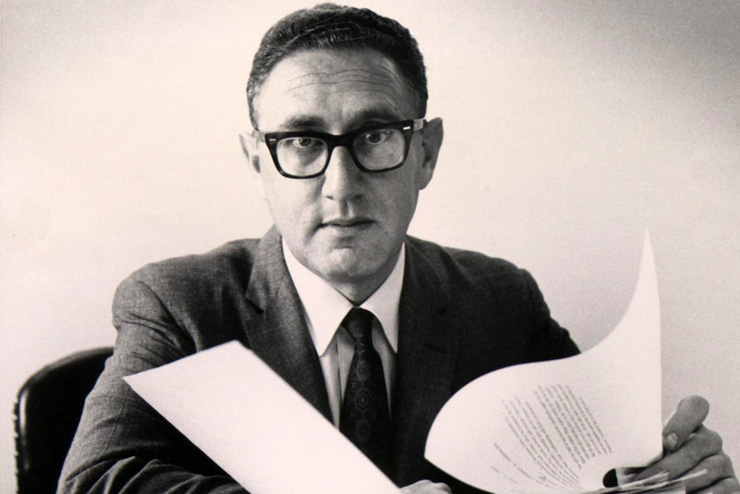

Henry Kissinger, who died at age 100 on Nov. 29, was the most prominent figure in the history of the United States to combine the roles of top-tier foreign policy theorist, strategist, and practitioner. Others have come close—most notably Zbigniew Brzezinski, Paul Nitze, and George Kennan—but Kissinger was in a league of his own. Unlike Brzezinski, he was not eternally beholden to his ethno-religious roots. Unlike Nitze, he was never a member in good standing of the WASP elite. Unlike Kennan, he was not a brooding loner prone to dark thoughts.

Kissinger was a complex and not particularly sympathetic figure. He was certainly a great man—a highly influential person whose intellect and abilities have had a tangible effect on history. He was, somewhat paradoxically, a major architect of U.S. foreign policy without ever becoming an “American.” This was one of his greatest virtues. He was resistant to the messianic urge—common to the bipartisan swamp—to claim that an imagined “America” is the vanguard of all progressive humanity. To his credit, Kissinger was immune to such Trotskyism in all its forms. He was an instinctive conservative, in the European sense of longing for order and peace.

Most obituaries failed to mention Kissinger’s seminal 1957 book, A World Restored: Metternich, Castlereagh and the Problems of Peace 1812–1822. originally written in 1954 as his enlarged Harvard Ph.D. thesis. This elegant early treatise on the 1815 Vienna Congress was penned many years before its author was called into government service and is the key to understanding his worldview. It celebrates pax as order, rather than “peace” in the sense of the mere absence of war. Its hero was Prince Clemens von Metternich, the central figure of the coalition, which defeated Napoleon in 1813-1815 and reestablished the balance of power in Europe.

Metternich was fixated on Ruhe (“quiet” in German), the calm of autocratic absolutism, to implement his vision of a pan-European peace architecture. All his life, Kissinger longed for a latter-day global Vienna system, an order agreed upon by all the major powers, which both legitimated and upheld it. He loathed the revolutionary concept of the U.S. “benevolent global hegemony,” which was relentlessly promoted by the neoconservative cabal starting in the 1990s.

Kissinger’s preference for balance has always led him, as a scholar, statesman, and sage, to favor engagement with rival powers rather than confrontation. He favored realism and its corollary, balance-of-power diplomacy, both of which Kissinger practiced with consummate skill as national security adviser and secretary of state. He stated then, and insists still, that peace is best kept through a distribution of power that moderates the appetites of the mighty. All along, Kissinger’s approach has been mercifully free from the ravings about America the “propositional nation,” the “indispensable nation,” the “virtuous nation,” or the ongoing mendacious lies about its “rules-based international order.”

The opening of China is perhaps the most significant single undertaking by Kissinger. He was until the end of his long life a believer that the Middle Kingdom can and should be America’s partner. He had no illusions that China would democratize and westernize, but he was convinced that the two powers could coexist and effectively run the world in partnership.

Kissinger was an upholder of the raison d’état as the foundation of foreign policy. He rejected the moralism of “our values,” especially when force-fed to a reluctant world. He knew that foreign relations will never be resolved once and for all, and always must be managed. His statement, last May, that “however Ukraine ends up, Russia must undoubtedly be included in the European framework,” is a sober statement of fact, in stark contrast to the prevailing “wisdom” inside the Beltway that casts Russia as a permanent pariah.

Kissinger’s life will be the subject of many biographies and dissertations. He will be remembered, most of all, for his ability to combine the experience of the statesman with the sensitivity of the historian. His argument in his 1994 book Diplomacy, that the United States can neither withdraw from the world nor dominate it, was sound and reasonable then, remains so now, and should be remembered for all time.

Leave a Reply