Everyone hails democracy as the government of the people, by the people, and for the people, but very few realize—or dare realize—that democracy actually represents one of the most perfect forms of tyranny, because it is one the average citizen is loath to acknowledge as such.

It is indeed very simply a matter of taking into serious consideration the basic definition of democracy as a political system in which the people are the only legitimate and therefore sovereign rulers, the only legitimate and therefore sovereign legislators, and the ultimate judge in all possible matters. History incontrovertibly shows that powerful men have not always been kind to their fellow men, and particularly to those expected to obey them. But instead of wondering whether this was owing to human frailty, our contemporaries have overwhelmingly deemed illegitimate not only any brute power but any authority exercised by some men over others. To add “without their consent” is highly ambiguous. The pupil’s consent to the teacher’s authority is not so much a consent as an obligation that he may, but should not, spurn. Whereas in a democracy, even if some obligation may arise from consent, there can be, since the citizen is sovereignly free, no obligation that preempts his sovereign freedom. So in democracy, true to its definition, citizens are still expected to obey some authority (in principle democracy is no anarchy), but whatever power is wielded is supposed to be each citizen’s very own: Each citizen obeys only the laws he is willing to obey—i.e., those he makes for himself.

Such definition of democracy is ritual but, as often happens with rites, its meaning is taken to be so clear as to be accepted without further ado, which in this particular case is a particular mistake. It is, I think, enlightening to make explicit what is here implicit—what is at the back of the true democrat’s mind, whether he cares to acknowledge it or not.

The first thing to clarify is the very idea of sovereignty: It is generally used as if it were a self-evident notion, which it is not. If properly understood, sovereignty is the qualification of a power or an authority, which not only supersedes any other but supersedes any conceivable bond, restraint, rule, law, norm, custom, or whatever, because it obeys no one or nothing but itself. This is why for centuries only God appeared fully to deserve such a qualification; having created all things, He was by definition the Lord of all things. In other words, sovereignty in the true sense is synonymous with absolute. There is scarcely any doubt why the word was used to qualify the so-called will of the people: “The people” is the new supreme lord of the new city; in a democracy there is no god but “the people.”

It is constantly claimed by scores of Christians that there is no reason why a democracy should not be Christian, because citizens may be overwhelmingly Christians. This is a fallacy, and Christian democracy an oxymoron, because it overlooks a dilemma. Either the citizens obey the laws of God over their own, because they consider the laws of God to supersede their own—in which case their will is not sovereign—or they obey the laws of God because, individually and collectively, they have decided to obey them, in which case the people’s will is sovereign, but not God’s. It is no happenstance that the primary aim of the French revolutionaries was not so much to overthrow the monarchy as to eradicate the authority behind it, the spiritual power of the Catholic Church (which they only tolerated provided the priests swore allegiance to the state, which is why they called the constitution civile du clergé). To put it in a nutshell, modern democracy has given birth to the first form of absolute power wielded by men over men. The legalization of abortion is emblematic: Men have availed themselves of a power that used to be exclusively God’s own, the power to give life to human beings and to take it back from them.

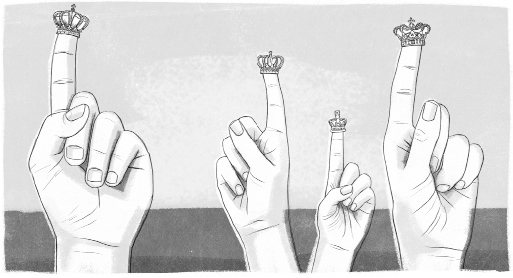

But that is not all. For all practical purposes, “the people” is an abstract notion referring concretely to nothing but a sum of concrete individuals, then called citizens. Concretely, whatever “the people” is supposed to be, it must logically be the sum of whatever its individual members are. Thus, to pronounce “the people” as a sovereign entity suggests that each citizen, being part of the sovereign, is a natural bearer of its sovereignty. The sovereign collective will of all must somehow be, if democracy means anything, the individual will of each citizen. Then, if someone is taught he is a citizen of a democratic society, it is only natural for him to assume he is invested with a sovereignty of his own. Democracy, if it is really true to its concept, implies it is not a shareholding company: Owning one share of stock out of 200 million or more is no individual sovereignty; it is a sham, a make-believe. Democracy implies that each citizen is entitled to consider himself able to rule over the entire political body. What else could it mean to vote?

Democratic ideology goes far beyond the utilitarian individualism with which it is so often confused. The self-centered, egoistic, but rational homo economicus, constantly intent on his own private benefit, does not dispute the similar right of others to fend for themselves. He is confronted with a situation in which it is up to him to be stronger, and he implicitly acknowledges the right of the stronger to win over the weaker. Man may be a wolf to man, for that is what men are by nature and forever. The self-centered democratic man is another kind of man altogether: He thinks he is a sovereign, entitled to lay down the only valid laws of the city. He deems his truth, since it is the only one valid for him, to be absolutely valid (to each his own), and therefore expects his truth to be respected by others. If not, he feels entitled to think he is denied justice. The economic tennis player, when defeated, yields to superior skill and tries to improve his game, whereas the democratic player claims the game was unfair. Which means there is a jungle potentially harsher than the free-market one, and it is the democratic social system.

To sum up, democracy is in principle a society in which an absolute power is conferred upon each citizen to use as he wishes, ideally regardless of the others, since it is individually absolute. From a purely logical point of view, democracy is therefore a potential absolute tyranny of each over the others. Based on these premises, the only question that remains is what democracy may turn out to be when men try to implement it concretely.

Logically, pure and perfect democracy cannot be but violent chaos, permanent disorder, revolution, systematic use of force, war of all against all. Pure democracy is exactly what Thomas Hobbes described under the name of “state of nature,” a condition in which all individuals are equally sovereign because they are all endowed with the same equal ultimate power to kill another man. But then, as Hobbes rightly surmised, pure and perfect democracy is rather unlivable: Concrete historical democracy has therefore always been a mitigated democracy, which means a society in which violence—tyranny—is not in the least abolished, but simply less apparent.

The main issue of democracy being to find a way for all citizens to be sovereign altogether at the same time, it readily appeared the simplest way to achieve this goal was for all citizens to be of one and the same will, one and the same mind. There could be no democracy unless unanimity prevailed among citizens. Thus, the French revolutionaries, J.-J. Rousseau’s devoted followers, declared that a true patriot’s will could not differ from another patriot’s will. What happened then was to be expected. Citizens could never be unanimous as long as they kept valuing whatever made each of them different from others: Unanimity meant uniformity, as complete as possible. Such uniformity implied for the private individual to renege on whatever made him distinctive, to be blotted out altogether by the citizen, for each citizen to become a man willing to be only what the others could be. Rousseau was only logical when he extolled in his Social Contract the “total alienation of the individual to the collectivity,” and Robespierre equally logical when he declared anything purely personal “abject.” But this was utterly unnatural all the same, so violence appeared necessary to implement unanimity: Citizens must be forced to be free, wrote Rousseau. And democracy ended in systematic terror, which occurred again with Soviet democracy.

It must be pointed out that it is the same undying need for a fusion of wills that periodically breeds the need for providential men supposedly to embody the will of the masses. From Robespierre to Lincoln, from Mussolini to De Gaulle or Roosevelt, from Lenin or Hitler to the particularly spurious Obama, the trend continues. There is a ceaselessly renewed need for leaders who lead the masses because, by catering to the most primitive passions and simplistic notions, they abolish all distance between themselves and the most basic citizen. Once such mobs and their self-proclaimed messiahs have overcome, they are naturally prone to stifle dissent, whether it be marginal within their ranks or radical outside: Unnatural creeds cannot afford to be tolerant. And if today the guillotine or the mental hospital is no longer the standard penalty, then ostracism (social death) is.

Fusional democracy prevails in times of turmoil, when irrational and emotional crowds may feel united by the feverish expectation of a radically new order of society in which all will be like gods. When the fever subsides, citizens are back to where they started from, which is basically a state of war of all against all. But civil wars and revolutions have taught the necessity of restoring some order to ensure some safer life (to reap less, but live to enjoy the harvest), even at the price of relinquishing some sovereignty: Tennis players agree to use rackets, not revolvers. Then the question becomes, Who is to make the rules that all must abide by? And here again lies a new fallacy.

Bargaining, compromise, trading off, discussion, argumentation—supposedly rational—and fair competition (if not between individuals usually reluctant to rely exclusively on Samuel Colt’s great equalizer, at least between organized political parties, trade unions, lobbies) are currently believed to have overcome civil strife and its daily bloodletting. But this is forgetting that when bargaining, each party strives to obtain the better part of the bargain: Trading off is not giving away, but trying to get the upper hand over someone who is trying to do the same—a continuation of war by other means. A war in which there is rather little loss of life or limb. (The powerful are obviously more accident prone than others, but the rank and file usually risk only lighter penalties, and even if articulate dissenters are delivered unto death, it is civil death.) But it is war, nonetheless: Even if democrats shy away from acknowledging it, how could there be anything but force ruling over all human intercourse, when by definition each citizen’s only legitimate standard is himself? A society in which norms are nothing but what each individual thinks should be a norm is a jungle where the only law is every man for himself and where no universal consensus may be spontaneously achieved. Rules are never equally beneficial to all parties, so that no law (or what passes for law) can even exist if not as the result of a contingent distribution of power that, as long as it endures, allows some to force it upon others. And since every citizen thinks of himself as a legitimate sovereign, why shouldn’t the ones in power demand absolute compliance with the power that they deem legitimately theirs? Thus, liberal democracy is the exploitation of man by man, and socialist democracy just the reverse: There is hardly any difference between the tyranny of the rich over the poor and that of the poor over the rich.

Whether it be a so-called charismatic leader, or a majority, or a minority who have managed to secure enough power, in a democracy right is might, and reason the opinion of the stronger one: Only the number of those who happen to agree makes a difference. Some will say there is wisdom in numbers. The fallacy never dies. Numbers are significant when inspired by a truth, not when they result from the momentary coincidence of individually sovereign judgments.

Thus the Hobbesian Leviathan is the only ideal democracy, the only way to ensure that some citizens do not simply become slaves to others, or even kill one another while asserting their respective sovereignty, because it is a city in which each citizen forfeits his personal sovereignty and consents to the absolute power of a referee forcing them all to respect some rules while all fending for their private benefit.

I will be told that all this is abstract thinking, and reality is not so dramatic. I have two answers. First, take a closer look: Is political correctness an abstraction? And second, wait and see. It is only because the inheritance of a civilized past (Christianity) is still living that we are momentarily spared the ultimate consequences of democracy, but the old Western soul may very well be about to enter new catacombs.

The true issue raised by democracy is henceforth why it is so overwhelmingly popular. The answer is, I think, as simple as it is sad: Once the average individual is taught he is potentially like a god and convinced the fault lies with others or the world if he does not actually live the life of a god, he can be expected not to give up hoping one day he will be like a god, and in the meantime to grasp at straws that make him believe he already is one, or to suffer being a slave in the hope that some day it will be his turn to be the master. This is what voting is all about.

In other words, democracy makes men unhappy and resentful, because of their obsessive self-centeredness. If they so often appear prone to pity, it is only because it gives them an opportunity to feel superior, for they only feel pity for those who experience evils that they fear for themselves. The only remedy for the tyranny of men over men, including the democratic one, is humility and objectivity, but this medicine is utterly repulsive to the democratic individual’s vanity.

Where are the times when youth was not a virtue but only a promise; when experience, the mother of all natural wisdom (the knowledge that men are not gods), was the only true title to rule over men; when faith gave a conscience to all, while the fear of God at least induced some tremor in the evil ones?

Leave a Reply