Fifty years ago, America’s deep state bent the scales of justice to reverse the landslide victory of a popular Republican president, run him out of office, and jail his top advisors.

This month is the 50th anniversary of the greatest political show trial of the 20th century, the Watergate Cover-up Trial, which lasted from October through December 1974.

We have reason to suspect that the entire story of Watergate is wrong—that justice was not done and that the American system, at least as envisioned in our Bill of Rights, did not at all work. In fact, during a time of intense political turmoil, the due process guarantees of America’s Fifth and Sixth Amendments were simply cast aside in an effort to destroy a president who was hated by the Washington “Deep State.”

What happened to Richard Nixon is all the more relevant today given that history is to some extent repeating itself in the political career of Donald Trump. He, too, has been branded as a criminal and subjected to an unrelenting barrage of legal actions designed to destroy his political power and reputation.

Something has changed since Nixon’s time. New perceptions stem from four terms, popular today but not used during Watergate’s unfolding: deep state, fake news, false narrative and—most relevant of all—lawfare, the improper use of criminal law to destroy one’s political enemies.

Given what we now know, it’s clear that these phrases describe what already existed during the Watergate scandal 50 years ago. Today’s public may also be willing to reconsider the customary narrative about Watergate in light of recent events. It’s become clear that the corrupt Watergate prosecutions did massive damage to the country. Nixon’s landslide 1972 re-election was deliberately voided, he was run out of office by lies and innuendo, and his senior aides were wrongfully convicted.

Five of the Watergate burglars had been caught red-handed on June 17, 1972 in the offices of the Democratic National Committee in the Watergate Office Building in Washington, D.C. They were convicted, along with their two masterminds, on Jan. 30, 1973.

That was the easy part. The greater question was, “Who else knew of the pending break-in in advance?” It turned out there was an extensive cover-up, seeing that the answer to that question cast suspicion on senior members of the Nixon administration.

The cover-up, run by Nixon’s lawyer, John Dean, collapsed in March 1973, leading to Nixon’s closest aides resigning in April. A newly created special prosecution team was brought in for what turned out to be a 10-month investigation. Seven individuals who were indicted on March 1, 1974 came to trial on Oct. 1. The trial, which ended on Jan. 1, 1975, saw the conviction on all counts of Nixon’s three top aides—Attorney General John Mitchell, Chief of Staff H. R. “Bob” Haldeman, and Assistant for Domestic Affairs John Ehrlichman. These men were convicted of conspiracy to obstruct justice, obstruction of justice, and perjury.

After the smoke cleared, they were the only ones whose convictions were upheld. The other four defendants avoided similar fates: Charles Colson pleaded guilty in a separate case, Gordon Strachan was removed from the trial at the suggestion of the circuit court, Ken Parkinson was acquitted by the jury, and Robert Mardian’s conviction was reversed and remanded on appeal. Neither Strachan nor Mardian was ever retried.

Following the verdict’s announcement, the lead Watergate prosecutor opined that “justice had been done,” while Washington Post reporter Carl Bernstein stated, “The American system worked.” Mitchell, Haldeman, and Ehrlichman were sentenced to terms of between 2½ to 8 years in prison; their sentences were later commuted and each ended up serving about 18 months of confinement.

I was the first to review the newly uncovered caches of papers, which detailed secret meetings, memos, and coordination… I was the first to realize they challenge everything we’ve been told about Watergate.

For the next 40 years, that seemed to be the end of the Watergate story. It turned out, however, that three special prosecutors took confidential internal files with them after they left office, which describe a coordinated plan to remove Nixon from office. Their documents did not begin to surface until 2013, when Special Prosecutor Leon Jaworski’s files were discovered at his law school alma mater, Baylor University, in Waco, Texas. Associate Special Prosecutor James Vorenberg’s staff meeting notes surfaced in 2015 among his papers at the Harvard Law Library’s so-called Treasure Room. Counsel to the Special Prosecutor Philip Lacovara gave his files to the National Archives in 2020. In addition to these revelations, the National Archives unsealed in 2018 Watergate prosecutors’ infamous “Road Map,” the secret report that directed the grand jury and the House Judiciary Committee toward the conclusion that Nixon must be impeached.

In each of these four instances, I was the first to review the newly uncovered caches of papers, which detailed secret meetings, memos, and coordination by and between officials in all three branches of America’s federal government. I was the first to realize the information in these documents challenged everything we’d been told about Watergate.

In the end, there are only three absolute truths about Watergate:

1) There really was a break-in. After all, the burglars were caught red-handed.

2) There really was a cover-up. The FBI later called John Dean the scandal’s “master manipulator” and credited him with 95 percent of the cover-up.

3) President Nixon really did resign. But, if we knew then what I uncovered in the past decade, Nixon would have finished his second term, and his aides would never have been brought to trial.

Even after 50 years, Watergate remains a complex and convoluted story, with few actual heroes and multiple villains. Instead of another recitation of its chronology, I’d like to take this anniversary opportunity to tell my own story by explaining the roles played by the various participants.

Why are story and insights worth considering? I had come to Washington in 1969, having been awarded a White House Fellowship two weeks after graduating with honors from Harvard Law School. I then joined the newly created Domestic Council, where I stayed for five years and served as deputy counsel on President Nixon’s Watergate defense team. In that capacity, I transcribed the infamous White House tapes, oversaw the document rooms holding the seized files of Nixon’s senior aides, and staffed his counselors on Watergate issues. I testified at the Plumbers Trial as a chain-of-custody witness. And, since I had handled an original tape when I had transcribed the “smoking gun” conversation held on June 23, 1972, between Haldeman and Nixon, which established the president’s knowledge of the cover-up, I was subpoenaed during the cover-up trial, too.

I am the only senior member of Nixon’s White House staff to possess a “clearance letter” from the special prosecutor certifying that I was never the subject of an investigation by their task forces. Still, by the time it was all over, I was largely unemployable.

I’ve spent much of the past 20 years researching the internal records of the Watergate Special Prosecution Force, which are held in the U.S. National Archives. In just the past 10 years, I’ve been the first to review caches of internal documents, improperly taken by three of the most senior Watergate special prosecutors. I have also analyzed their infamous “Road Map,” unsealed in 2018 in response to my court petition.

Although these are my personal insights and opinions, they are based on extensive personal experience. It is as though I was engulfed by an immense political conflagration, which consumed all my colleagues. Fortunately, I emerged largely unscathed. Then, 30 years later, I decided to return to the scene and to sift through the ashes.

Attitudes and Actions of the Players

G. Gordon Liddy (1930–2021). There were only two real criminals in Watergate. Liddy was one of them.

I knew Liddy from my fellowship year at Treasury. From my understanding, it seems that he was promised a federal appointment if he would drop out of a congressional race in upstate New York. He ended up as a special assistant to the secretary of the Treasury, reporting to Gene Rossides, assistant secretary for enforcement and operations. Rossides’ responsibilities included supervision of the Bureau of Customs, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (ATF), and the Secret Service. The ATF was intensely disliked by gun owners, and Liddy positioned himself as the gun owners’ advocate within the department, frequently giving speeches highly critical of ATF rules and regulations. This brought him into conflict with Rossides, who successfully got Liddy fired from Treasury.

Over my strong objections, Liddy was placed on the Domestic Council staff by my immediate supervisor, Bud Krogh, largely to spite Rossides. Liddy was then assigned to the newly created Special Investigations Unit, which had been formed in response to the Pentagon Papers leak. This unit was known as The Plumbers, because their purpose was to prevent further leaks of government information. In that capacity, Liddy together with his colleague, former CIA agent Howard Hunt, helped mastermind during Labor Day weekend 1971 an unsuccessful break-in at the Beverly Hills offices of the psychiatrist Dr. Lewis Fielding. The purpose of this break-in was to find information that would discredit Dr. Fielding’s patient, the Pentagon Papers whistleblower, Daniel Ellsberg. This was of little immediate consequence at the time, but 10 months later these same burglars were caught red-handed in the DNC offices of the Watergate.

While the Watergate break-in could be (and was initially) dismissed as an unauthorized operation by junior campaign officials, responsibility for the earlier invasion of Dr. Fielding’s office could be traced to senior White House officials, whose offices were in the West Wing. Hence, one of the chief reasons for a cover-up was to prevent the discovery of a connection between such illegal acts and the president’s offices.

In the interim, Liddy had been recruited by John Dean to develop a campaign intelligence plan for Nixon’s re-election committee, The Committee for the Re-election of the President (CRP, pronounced “creep”). The purpose of such a plan is to gather intelligence on political opponents. All campaigns have developed such intelligence plans; today it’s called opposition research and the efforts to spy on one’s opponents are usually not illegal. But at CRP, Liddy’s criminal mind found its full expression in proposals for mugging, bugging, kidnapping, and prostitution. While one may be tempted to dismiss my characterization as exaggeration, I’m basing it on how Liddy described his plans in his 1980 autobiography, Will.

Liddy showed up at CRP in December 1971, announcing he’d been promised at least a half million dollars for his intelligence plan, which he named “Gemstone.” CRP’s acting director, Jeb Magruder, responded that the only one with the authority to approve expenditures of that amount would be CRP Director John Mitchell, who had not yet left his position as Nixon’s Attorney General. Magruder therefore arranged for Liddy, Dean, and himself to meet with Mitchell at the Department of Justice in January 1972. Liddy presented his plan then, which was not approved at that meeting or at a subsequent one held a week later.

The five burglars were arrested early Saturday morning, June 17,1972, at the DNC headquarters, and the Watergate Scandal officially began. No one on Nixon’s White House staff appeared to be in any danger, but it was clear that the folks at CRP were in deep trouble. The ensuing cover-up was intended not only to prevent any connection with the Fielding break-in, but to protect Liddy, Dean, and Magruder, all of whom met in the attorney general’s office to discuss Liddy’s plans.

At this point, it should be noted that neither Nixon nor any of his senior staff had ever met Gordon Liddy nor had they any idea of his campaign intelligence plan. But the CIA did.The agency’s staff had prepared the display charts that Liddy used to describe his Gemstone plan.

Liddy was fired from CRP shortly after the break-in arrests. Later he was among the seven indicted for their roles in the break-in: the five caught red-handed and the two masterminds, Liddy and Hunt. Liddy adhered to a strict code of silence thereafter—omertà—gaining cult status as “the iron man of Watergate.” He was imprisoned in excess of six years, by far the longest jail term meted out to any Watergate accomplice, until his sentence was commuted by President Carter in 1977.

But Liddy was not part of the cover-up trial that took place in 1974. His actions were the moving force in the Watergate scandal, but he hadn’t been involved in Dean’s cover-up machinations.

Emerging from prison in the 1980s, Liddy hosted a radio talk show in Washington, gaining popularity as a knowledgeable and thoughtful commentator. This was a huge change in his persona from his previous days with the Plumbers. People who knew him then remember him more as a scary right-wing radical; like someone soaked in gasoline, running around asking people for a match.

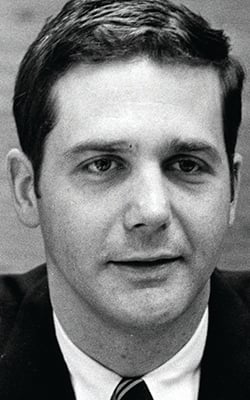

John Dean (1938–present). The other real criminal in Watergate was the president’s own lawyer, John Dean. Dean and I joined Nixon’s White House staff at roughly the same time. He succeeded John Ehrlichman as counsel to the president in July 1970. My fellowship year ended that August, when Ehrlichman placed me on the newly formed Domestic Council. Our jobs, however, were considerably different. Ehrlichman had taken his staff with him when he became assistant to the president for domestic affairs, while Dean was left with no staff and no real responsibilities. He held what was called a “process” job.

Dean himself has dismissed his position as little more than “a highly paid messenger boy” between Bob Haldeman and John Mitchell, adding that “the title was the best part of the job.” As one example of Dean’s substantive irrelevance, there is no record of Dean meeting with or submitting memos to Nixon during the first two years of his appointment, except for this one occasion: to witness Nixon executing an updated will prepared by his former law firm.

In contrast, mine was a “substantive” job since I was charged with staffing law and order initiatives on behalf of the president. Within two months of my arrival, I coordinated Nixon’s visit to the Department of Justice to sign the Organized Crime Control Act of 1970, which I had helped draft. This was the first of many interactions, both written and personal, with President Nixon.

Dean’s office was down the hall from mine in the Old Executive Office Building. I never cared for him, because he partied in Georgetown far more than he worked on policy issues. I even told my supervisor, Bud Krogh, that I didn’t want Dean on any of my policy teams because he didn’t pull his weight. Bud explained that Dean was supersensitive about his own relative standing on the staff, and he agreed to deal with him directly. Dean returned the favor to Krogh by convincing him to perjure himself before the grand jury. My distance from Dean no doubt saved me.

Dean had both recruited Liddy to prepare his campaign intelligence plan and was present in Mitchell’s office for its presentation. While these actions constituted a clear but undisclosed conflict of interest, he quickly assumed leadership of the cover-up. He was later disbarred for his actions, which included encouraging others to commit perjury, destroying evidence retrieved from Hunt’s safe in the Old Executive Office Building, embezzling $4,000 of campaign funds to pay for his honeymoon, and authorizing the distribution of “hush money” to the Watergate burglars.

When his cover-up collapsed in the spring of 1973, Dean was the first to approach prosecutors in pursuit of personal immunity. He initially offered to testify against former CRP officials, including John Mitchell and Jeb Magruder. When no immunity offer was forthcoming, he changed his story to accusing Nixon’s closest aides of supporting his cover-up actions. He also shared records taken from his counsel’s office describing other possible misconduct (characterized by Mitchell as “the White Horrors”) but career prosecutors were not interested.

When even that didn’t result in an offer of immunity, Dean’s well-connected Democrat lawyer approached the newly created Senate Ervin Committee, who gave Dean immunity in exchange for testimony against his former colleagues. Dean thus became the committee’s star witness, portrayed as some sort of innocent whistleblower, rather than how the FBI saw him: as the cover-up’s master manipulator.

Dean also became the special prosecutor’s principal witness in the cover-up trial. To increase his credibility, Judge Sirica sentenced Dean to a prison term of one-to-four-years, with incarceration to begin on the trial’s first day, when Dean was chosen to be the opening witness. Then, seven days after the trial’s conclusion, Sirica reduced Dean’s sentence to time served, a total of less than four months of technical confinement. It came to light that Dean, unlike Liddy, had never spent a single night in jail. Instead, he was kept at a witness holding facility in nearby Fort Holabird, Maryland, where he had an office and conjugal visits from his wife.

Watergate’s two core criminals received far different treatment: one was jailed for over six years, the other not at all.

Dean has since become a frequent television commentator, inevitably introduced as a former counsel to the president. CNN wheels him out every time there is a GOP scandal so that he can proclaim it to be “worse than Watergate.”

Egil “Bud” Krogh (1939–2020). A little known but key figure in the Watergate saga is Bud Krogh, one of the most popular members of Nixon’s White House staff. Bud had lived with the Ehrlichman family in Seattle, clerked for his law firm during the summers while attending law school, and formally joined Ehrlichman’s firm upon graduating in 1968. He soon joined Ehrlichman as a member of Nixon’s presidential transition team and followed him as deputy counsel at the White House and then as the Domestic Council’s associate director.

Krogh bore a heavy burden of responsibility for the events of Watergate, since he was primarily responsible for putting the two chief actors in place. He arranged for Dean to succeed Ehrlichman as the president’s counsel in July 1970 and then put Liddy on his staff in 1971. Krogh reacted to the strain of the unfolding investigation in a surprising manner. At Dean’s behest, he lied to the grand jury concerning details of the Fielding break-in and was the first member of the Nixon administration to be indicted. He then chose to plead guilty and to become the government’s lead witness, testifying against his former mentor in authorizing the Fielding break-in.

In another surprising twist, after the scandal Krogh toured the country with Daniel Ellsberg, the Pentagon Papers leaker. I still marvel, in retrospect, that Krogh personally approved members of his own staff to break into Ellsberg’s psychologist’s office; then he went hand-in-hand with Ellsberg, decrying his earlier efforts to stop government leaks.

Jeb Magruder (1934–2014). Magruder was a minor staffer at the Nixon White House. He was charged with the unenviable task of improving Nixon’s standing with the media. Perhaps understandably, he failed miserably. When Charles Colson assumed management of Nixon’s communications unit and was told Magruder came with that staff, he is reported to have said, “I don’t want him. Send him over to CRP, where he can’t do much harm.”

In any event, Magruder was dispatched to CRP in late 1971 to help organize the fledgling campaign committee. He asked John Dean for recommendations for a lawyer to help assure compliance with the newly enacted campaign finance legislation. Dean soon responded that he was getting a twofer: Gordon Liddy would be CRP’s general counsel, with responsibilities for both campaign finance and campaign intelligence.

It was Magruder who decreed that only Mitchell could authorize campaign intelligence expenditures of the amounts Liddy envisioned, which is why those two meetings were held in the attorney general’s office.

Liddy quickly concluded that Magruder was an idiot and, at one point, even threatened his life. Knowing Liddy as I did, this was not an idle threat. Magruder wanted Liddy fired immediately. Dean intervened and suggested reassigning Liddy to be general counsel of the Finance Committee under Maury Stans. In his new post, Liddy would retain responsibility for the intel plan.

Mitchell arrived at CRP on March 1, 1972, but didn’t have much time for Magruder until March 31, when they met to discuss pending issues. The last item on their list was Liddy’s intel plan, now priced at $250,000. Three people were in the room at the time: Mitchell, Magruder, and Fred LaRue, a Mitchell loyalist. Both Mitchell and LaRue swore that Mitchell’s reaction to Liddy’s scheme was, “What this again? I don’t want to see this ever again.” Magruder swore Mitchell’s reaction was the opposite: “Let’s give him the money and see what he can do with it.”

Regardless, Magruder acted as though Mitchell had given his approval and authorized the payment of Liddy’s invoices, as submitted. Following the break-in arrests, it was feared that Magruder would not be strong enough to survive the scrutiny on his own, so he was kept on CRP’s staff, where he would be protected by Dean’s cover-up. Dean even helped Magruder rehearse his perjured grand jury testimony.

As the cover-up began to collapse, Magruder panicked and raced around begging Mitchell, Dean, and LaRue for assurance that they would continue to back up his false testimony. Naturally, his panic had the opposite effect on those three men, setting off a race between them to seek immunity from prosecution.

Magruder became so paranoid over what he had done that he was willing to “remember” whatever deed of his former colleagues he thought prosecutors would appreciate. It got so bad that the prosecution team couldn’t trust anything he said. One of the prosecutors, Jill Volner, recounted Magruder’s behavior in her 2020 book, The Watergate Girl, in a chapter titled, “The Watergate Boy.” She wrote:

He had lied and lied and lied. To the FBI, to Justice Department investigators, to a federal grand jury, to Judge Sirica.…

Lying was as natural to him as breathing.…

You might think lying was a part of Magruder’s DNA.…

No witness in my experience had affected me the way Magruder did. I was stunned by the ease with which he dissembled, even as he tried to clear himself. He was a slippery confabulator, and I came to the conclusion based on our conversation that he had no moral center.…

Lawyers are not supposed to put witnesses on the stand who they know are going to lie. Even James Neal, the lead Watergate prosecutor, confessed to Nixon’s lead defense counsel that he wasn’t sure they could put Magruder on the stand for precisely that reason. But prosecutors went right ahead and made an exception with Magruder. He was second only to Dean as the government’s lead witness at the trial. Volner explained the decision:

Magruder wasn’t telling us the whole truth. Still, we needed him badly. He was the only key figure in the planning of the break-in and the early development of the cover-up whom we were likely to secure as a witness, and he was the bedrock of any case against his former boss, John Mitchell.

Magruder appeared before the grand jury on five separate occasions and had 14 intensive interviews with various prosecution teams. His memory turned to mud, and he appeared willing to swear to anything he thought would please prosecutors. Even later in life, his Watergate stories were constantly changing.

One could argue that a substantial part of the Watergate cover-up involved providing cover for Magruder’s personal weaknesses. Those weaknesses contributed substantially to the bringing down of a president.

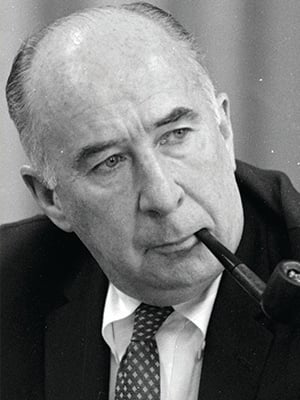

John Mitchell (1913–1988). Mitchell was Nixon’s law partner in their New York firm, Nixon Mudge, where he had invented the “moral obligation” municipal bond, whose issuance allowed communities to incur debt without a bothersome public vote. He had been overall director of Nixon’s successful 1968 campaign, but he didn’t want to come to Washington out of concern for how living in that notoriously booze-driven city might affect his alcoholic wife, Martha. But Nixon prevailed and Mitchell became his first, and very formidable, attorney general. Mitchell enjoyed being

attorney general so much so that he delayed resigning in 1972, when he was supposed to assume leadership of Nixon’s reelection campaign.

Out of fairness to Mitchell, it is not unreasonable to conclude that he was set up and ill-served by Magruder’s decision to seek his budgetary approval for Liddy’s campaign, and that he never actually approved it. Look at it from Mitchell’s point of view: Here were three people in his office, all formerly of Bob Haldeman’s staff at the White House, telling him about a crazy campaign intelligence plan that he’d never heard of before. At least he got them out of his office without a ruckus. But his stoic and muted response ended up costing him his reputation, his freedom, and his spouse, who divorced him during the scandal.

Mitchell resigned from CRP on July 1, 1972, and moved back to New York City, just two weeks following the break-in arrests. At that time, everyone believed his action was taken out of concern for Martha’s alcoholism. There is no record of Mitchell having seen or spoken to the president until March 22, 1973, when he was summoned to Washington to help respond to Hunt’s blackmail demands.

Others at the White House suspected Magruder was right, and that Mitchell had, indeed, approved the budget for Liddy’s plan. How else could it have gone into effect? But Mitchell was adamant that he had done no such thing.

Mitchell spent half his defense effort during the cover-up trial maintaining that he had never approved Liddy’s plan and consequently had nothing to cover-up—

particularly from New York, where he had returned to the practice of law shortly after the break-in arrests.

After a three-month trial, the jury found otherwise. Mitchell was found guilty on all counts, disbarred, and served 19 months at a federal prison camp inside Maxwell Air Force Base in Montgomery, Alabama, before being released on parole for medical reasons.

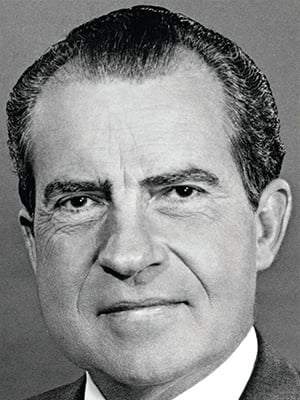

Richard Nixon (1913–1994). In 1968, Nixon was elected America’s 37th president. He was first elected to Congress in 1946, to the Senate in 1950, as Eisenhower’s Vice President in 1952, and again in 1956. He had lost exceptionally close races to Jack Kennedy for president in 1960 and in the California governor’s race to Pat Brown in 1962, after which he retired to New York to practice law. He had eight years to think about what he would do, should he ever get elected president.

When inaugurated on Jan. 20,1969, Nixon was opposed by every institution in our nation’s capital: by both chambers of Congress, by their staffs, by the federal bureaucracy, by the media, and by most law firms, think tanks, and lobbying firms. Still, he had an extraordinarily successful first term, with substantial accomplishments in both foreign and domestic affairs.

He won a landslide reelection in 1972, only to lose everything in the Watergate scandal. He had resigned two months before the cover-up trial began, but prosecutors used the trial to portray the president as intimately involved in the cover-up.

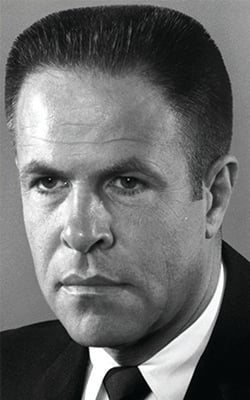

H. R. “Bob Haldeman (1926–1993). Bob Haldeman was a senior executive at the J. Walter Thompson advertising agency. He had been an “advance man”—arranging campaign events and handling publicity—for Eisenhower in 1956 and for Nixon in 1960. He was a strict taskmaster and is credited with authoring that era’s definitive manual for advance men.

As Nixon’s closest advisor from 1969 to 1973, Haldeman was possibly the ideal chief of staff. He had absolute control over who Nixon saw and what he read but had no political agenda of his own. His only goal was to be sure Nixon had sufficient information to make knowledgeable decisions and that he was loyally served by his political appointees.

I was terrified of Haldeman. No good could come from drawing his attention, which could only result from some mess up on my part. Fortunately for me, that never occurred. I worked on policy issues on the Domestic Council under Ehrlichman and safely out of Haldeman’s notice, which was a most pleasant place to be!

Haldeman took an interesting approach in defending

himself during Watergate. He never refused to testify, which was his right under the Fifth Amendment. Instead, his approach was something like: “I don’t think my actions were criminal, but I’m not a lawyer. I will answer all you questions and tell you everything I did. It was always in aid to the president I served. Whether you think that was criminal is up to you.”

His only Watergate involvement stemmed from some $350,000 of campaign contributions that had been set aside before the new campaign law had come into effect. When CRP needed funds to pay legal expenses and humanitarian aid to the Watergate burglars, Haldeman volunteered to return this money to CRP. The issue at trial was whether he did so out of kindness, or to buy their silence. Dean testified that it was for both reasons, which led to Bob’s guilty verdict.

Along with Mitchell and Ehrlichman, Haldeman was convicted on all counts—conspiracy, obstruction, and perjury—and served 18 months at Lompoc Federal Prison near Los Angeles.

John Ehrlichman (1925–1999). Ehrlichman was head of scheduling during Nixon’s 1968 campaign and named his first Counsel. He was intimately involved in domestic policy issues from the outset. He was named assistant to the president for domestic affairs and director of the newly created Domestic Council in July 1970, when he invited me to join his staff.

Ehrlichman and Haldeman were accused of forming a “Berlin Wall,” that kept others, even Cabinet members, from pitching proposals directly to the president. This was Nixon’s wish, however, since he was notoriously unable to reject personal sales pitches. What Nixon wanted was to have such ideas presented in writing, along with alternative choices, such that he could think them through during afternoon sessions in his hideaway office in the Old Executive Office Building, much like a judge considering appellate briefs.

For my part, I authored dozens of such option papers advancing policy proposals. It was a tightly run system: foreign affairs proposals were staffed by Henry Kissinger’s National Security Council, while ideas for domestic initiatives came from Ehrlichman’s Domestic Council, in a system enforced by Haldeman’s procedures.

Like his UCLA classmate and lifelong friend, Ehrlichman was only tangentially involved in Dean’s cover-up. There was a separate source of funds from Nixon’s California friends that came through his personal attorney, Herbert Kalmbach, but the agreement was that Herb would not be asked to raise money for CRP during the

re-election campaign. Following Nixon’s victory, and when Dean was seeking money for the burglars’ support, Ehrlichman agreed to ask Kalmbach for help. As with Haldeman, Ehrlichman’s possible guilt turned on his reasons for helping Dean—which Dean testified included buying the burglars’ silence.

Unlike Haldeman, however, Ehrlichman was not aware of Nixon’s secret taping arrangement—the recordings from which were the moving force in sinking Nixon’s presidency—a secret for which he never forgave Haldeman or Nixon.

I’m certainly biased, but of all the major Watergate figures, I believe John Ehrlichman was the most ill-used.

John Sirica (1904–1992). “Maximum John” Sirica was chief district judge during Watergate and appointed himself to preside over both the burglary and cover-up trials. His elevated position came from seniority and not from merit or the respect of his judicial colleagues. He was the most reversed judge in the D.C. circuit, largely because of his practice of denying defendants the due process rights guaranteed by the Fifth Amendment.

The best description of Sirica is an article by New Yorker writer Renata Adler that appeared in Harper’s Magazine in August 2000. This came after Adler had been severely criticized for declining to review Sirica’s book. She described the judge as a “corrupt, incompetent, and dishonest figure, with a close connection to Senator Joseph McCarthy and clear ties to organized crime.”

Adler’s article details many of Sirica’s shortcomings, and appeared well before the caches of internal prosecutorial documents that I’ve uncovered, which record Sirica’s surprising series of secret meetings with Watergate prosecutors, his “temporary” harsh sentencing of John Dean to increase Dean’s witness credibility in the cover-up trial, and the prosecutors’ own reservations about Sirica’s appointing himself to preside over that trial.

Sirica was, in short, an ignorant, arrogant, and incompetent judge, who was neither objective nor unbiased. Naturally, Time magazine named him as their “Man of the Year” in 1973 for his conduct during the burglary trial.

David Bazelon (1909–1993). Bazelon was chief judge of the D.C. circuit and guilty of questionable conduct prior to receiving his judicial appointment from President Truman. A book by Gus Russo, Supermob (2006), describes how Bazelon, while director of the Office of Alien Property—charged with selling off assets seized during World War II from German and Japanese collaborators—secretly

favored his Chicago friends, who were part of the Jewish Mafia. Russo claims Bazelon was later rewarded as a private investor in purchasing those very same assets and quotes Bazelon as saying that he’d be in jail if he hadn’t received a judicial appointment. Interestingly, this was a recess appointment by Truman, so there was no FBI investigation of Bazelon’s background prior to his taking office.

By 1973, Bazelon had been chief judge for 11 years and controlled a bloc of five liberal judges, who formed the circuit’s absolute majority. In October of that year, Archibald Cox, the original special prosecutor, became so concerned with Sirica’s pro-prosecution rulings that he feared they would win convictions at trial, but be reversed on appeal by Bazelon’s liberal majority. He thus approached Bazelon in a highly improper secret meeting and urged him to stack the deck on any appeals. As Cox explained, if the full court sat on appeal, Bazelon’s liberal bloc of five would always be in the majority—which is precisely what Bazelon did on all 12 appeals from Sirica’s criminal rulings.

Bazelon’s only mistake was that his law clerk, Ronald Carr, was in the room during Cox’s meeting and, years later, shared this story with his former law partner, who was about to be sworn in as judge on the same D.C. circuit court. That judge, Laurence Silberman, relayed Carr’s story to me in 2008. I well remember his words: “Imagine, the much-vaunted Archibald Cox of the Harvard Law School making a secret approach to the very chief judge who was going to hear appeals from these cases!” Silberman repeated the story for a Federalist Society video in 2021, shortly before he passed away.

Judicial and prosecutorial wrongdoing during Watergate reached even the appellate court level—but we didn’t know it for almost 40 years.

Elliott Richardson (1920–1999). Richardson was nominated by Nixon in 1973 to succeed John Mitchell as attorney general. It was not a post he sought. He was known as “Mr. Resume.” A graduate of Harvard and Harvard Law School, Richardson had been U.S. attorney in Boston before being elected lieutenant governor and then attorney general of Massachusetts. In the Nixon administration, he’d been undersecretary of State, secretary of Health, Education and Welfare, and secretary of Defense. He was extraordinarily well-positioned to run for president at some future point. Becoming Nixon’s attorney general in the midst of the Watergate saga could cause him to prosecute fellow Republicans and besmirch his impressive reputation. But Nixon insisted, especially since Richardson was not involved whatsoever in Watergate.

Senator Edward Kennedy controlled the Senate Judiciary Committee during his confirmation hearings and insisted, as a condition of confirmation, that Richardson appoint a special prosecutor acceptable to the committee, who would operate with complete, unreviewed independence from the Department of Justice. Richardson happily agreed to this arrangement, which would remove him completely from Watergate involvement. He even agreed to appoint Archibald Cox, his Harvard law professor, as special prosecutor.

Cox, in turn, appointed his fellow law professor, James Vorenberg, as associate special prosecutor. Vorenberg did all the hiring for the Watergate Special Prosecution Force (WSPF), whose confidential Table of Organization and Employment envisioned hiring 92 specially recruited individuals—virtually all of whom already hated President Nixon. The top 17 prosecutors had all worked in the Kennedy/Johnson Department of Justice. They were almost uniformly Ivy League educated. They called themselves “Cox’s Army” and labeled their phone directory “The Best and the Brightest.”

Thus, primarily due to Richardson’s political ambitions, the Watergate prosecutions represented a constitutional inversion: The very people who lost power with Nixon’s 1968 election were now in charge of its investigation and prosecution.

When Nixon realized the full extent of that onslaught, particularly after Vorenberg announced at their first press conference that they intended to investigate each and every allegation of wrongdoing since Nixon had taken office in 1969, he decided to remove Cox and bring WSPF under the supervision of the Justice Department’s Criminal Division.

While there are other versions of what happened, this is taken from Inner Circles (1992) by Alexander Haig, who had replaced Haldeman as Nixon’s chief of staff. Richardson, who would have to take responsibility for repositioning WSPF, suggested a way they might get Cox to resign in protest instead. When his idea failed, Cox defiantly didn’t resign, and Richardson was called upon to fire Cox, Richardson chose to resign instead.

Richardson exited a media hero, with his sterling reputation intact, but to those who know the inside story, he remains an arrogant and spineless weakling, who ill-served a president who had treated him so well.

Leon Jaworski (1905–1982). Jaworski had a somewhat checkered background before coming to Washington in 1973. He is named in a 2005 book by Jack Hamann, On American Soil, How Justice Became a Casualty of World War II, which recounts how Jaworski, while an Army prosecutor, deliberately hid exculpatory evidence from defense counsel that would have prevented a platoon of black soldiers from being court-martialed.

Decades later, Jaworski succeeded Archibald Cox as special prosecutor, following the latter’s departure in the Saturday Night Massacre—as the series of resignations following Nixon’s decision to fire Cox came to be called. Jaworski had parachuted into a raging battle in which he was distrusted by both sides. He brought no staff with him, not even a secretary, but quickly learned to suspect bias from the WSPF staff—which he complained about when he told his deputy that the feeling from the staff was that “the president must be reached at all cost.”

It seems clear from his confidential files, which he took with him when leaving and which didn’t surface for 40 years, that Jaworski began by insisting that WSPF attorneys concentrate on building criminal cases. But Jaworski got rolled and eventually joined Cox’s holdover staff in secretly helping the House Judiciary Committee conduct its impeachment inquiry.

The enduring mystery of Jaworski is what he told grand jurors in February 1974 to convince them to name Nixon as a co-conspirator in the Watergate cover-up indictments that were announced on March 1. After all, once their “Road Map” (said to lead to Nixon’s impeachment) was unsealed in 2018, it became clear that Nixon had committed no crime that could serve as the basis for impeachment. The Road Map was all smoke and mirrors.

The naming of Nixon in a criminal indictment, even if he was not actually indicted, was a separate matter from sending grand jury evidence to Congress to assist with his impeachment. In spite of extensive efforts, what Jaworski told those grand jurors about Nixon’s supposed criminal actions remains sealed to this day.

Jaworski is still seen as a Watergate hero—the leader of the group that drove Nixon from office. His self-documented secret interchanges with Sirica, however, tell a tale of massive due process violations that completely taint the cover-up trial.

Bob Woodward (1943–present). Woodward’s famous reputation as an investigative reporter stems from information provided to him by a secret government source, later nicknamed “Deep Throat.” We might ask why merely passing along what one learns from such a source justifies being called the greatest investigative reporter of all time. Angelo Lano, for example, the lead FBI agent on Watergate from the morning of the break-in arrests to the cover-up convictions 30 months later, told an archivist with the National Archives during an oral history in 2007 that Woodward and his partner Carl Bernstein provided no useful information. “They were reporting what we already knew,” he said. “Leads? Not a one. Did we give them any? Thousands.”

Perhaps worse is Woodward’s deliberate misdirection. For 30 years, he allowed—even encouraged—people to believe Deep Throat was a member of Nixon’s White House staff; an individual who had become so disgusted with the criminality that he was leaking information to Woodward. It was not until 2005 that we learned that Deep Throat was a former FBI agent who was upset that he had not been named to succeed J. Edgar Hoover. Woodward’s deliberate misdirection is both fraudulent and despicable.

Similarly, there is Woodward’s effort to identify and interview grand jurors, which are acts punishable by law. This was stoutly denied until 2012, when an author working on a book about Washington Post Executive Editor Ben Bradlee came across a seven-page typed memo written by Bernstein that describes such an illegal interview. When confronted, Woodword threatened to ruin the author, Jeff Himmelman, should he reveal that information. His threats were to no avail, and Himmelman published the information in See Yours in Truth, a Personal Portrait of Ben Bradlee. The feds have not yet decided to arrest their favorite reporters.

Finally, there is the astounding missed opportunity from Woodward’s interview of Dec. 5, 1974, with Leon Jaworski, which took place while the cover-up trial was still pending. The second sentence on the top page of Woodward’s notes reads: “Sez there were a lot of one-on-one conversations that nobody knows about but him and the other party.”

What a tantalizing statement! Just who could Jaworski have been referring to? It seems obvious in retrospect, especially in light of Jaworski’s confidential files, that he could only have been alluding to his series of secret meetings and conversations with Judge Sirica. Jaworski was begging to confide this information to Woodward, which would have blown the top off the corrupt Watergate prosecutions—and we wouldn’t have had to wait 20 more years for the truth to come out. But exposing the corruption of the Watergate prosecution was not in Woodward’s political interest.

Given what we now know about the corrupt conduct of the Watergate judges and prosecutors, two actions should follow.

First, the Justice Department should unseal the transcript of whatever Jaworski told grand jurors back in February 1974 to convince them to name Nixon as a co-conspirator. We asked for this disclosure once their action became public in 1974. We asked for it again in a cross-appeal in U.S. v Nixon. We asked for it as a part of my petition to unseal the “Road Map” in 2011, and we asked for it again in a petition to the Department of Justice in 2021. Given what has become public already, the odds are overwhelming that Jaworski asked grand jurors to act without ever specifying an actual criminal act by Nixon himself.

Second, the Department should launch an internal investigation of past wrongdoing by Justice Department attorneys in pursuing and prosecuting the cover-up case, particularly in light of the dozens of offending documents I’ve uncovered in the last 10 years.

Unfortunately, I don’t think any of this will happen unless there is a change in the management of the Justice Department. Current officials declined to review the documents I’ve uncovered or even to look into my allegations. They actually assured me, in writing in a letter dated Aug. 22, 2022, that they bore no responsibility for any wrongdoing by WSPF attorneys. They explicitly denied that the attorneys involved were a part of the Department of Justice.

One suspects a Trump administration might be more interested in pursuing allegations of lawfare, no matter from when. As the case of Nixon shows, Washington’s deep state has been using the legal system to destroy inconvenient presidents long before Donald Trump, and it will continue to do so until its corruption is exposed and addressed.

Leave a Reply