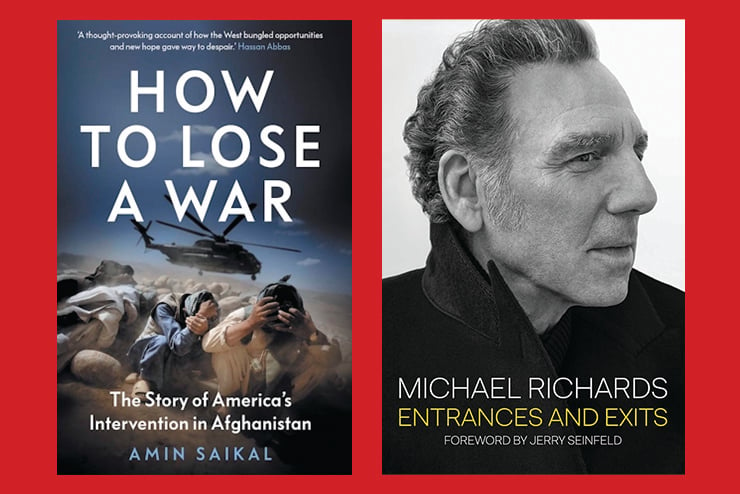

How to Lose a War: The Story of America’s Intervention in Afghanistan, by Amin Saikal (Yale University Press; 320 pp., $30.00). Amin Saikal is not a conservative. Nor is he a “foreign policy realist” concerned with “national interest,” nor a defender of Christian or Western civilization. He is, rather, a liberal who approves of using military force to spread “liberal democracy” and who holds an emphatically favorable view of most variants of Islam.

But Saikal is also a man willing to face facts, and in doing so has written a devastating critique of the 2001-2021 Afghan War.

He begins by assessing the lack of a coherent American strategy—a problem rooted in failure to understand the Afghan people. The U.S. forces assumed they would obliterate the Taliban and Al Qaeda and a new, stable, and friendly democratic government would arise in their place.

Instead, the Taliban was able to keep military forces in the field despite losing control of much of the country. Al Qaeda remained largely intact, in part because of inept policy. For the sake of appearances, senior U.S. military commanders initially wanted Osama bin Laden captured by America’s Afghan allies. For months after the war began, better-qualified American units were given less important tasks.

Neither were U.S. leaders’ political expectations fulfilled in a country of tribes, chieftains, and warlords. Few Afghans were interested in democracy; fraudulent elections were often just another way to gain power. Those allied to the U.S. who were powerful enough to create a stable new order typically wanted to preserve their traditional forms of leadership.

In principle, Saikal favors American efforts to move Afghanistan from traditionalism to “liberal democracy.” In practice, he recognizes that Afghanis do not want democracy and that American intervention couldn’t impose the cultural changes needed for that titanic political transition.

To his credit, Saikal demonstrates that combating terrorism and spreading “liberal democracy” are not (as the Bush administration claimed) mutually reinforcing objectives and can even be mutually exclusive. In the case of Afghanistan, attempting to establish “liberal democracy” created the instability and power vacuums that allowed the Taliban to regain power.

The last fatal flaw Saikal identifies is overextension. The Bush administration claimed the “War on Terror” required fighting on two fronts—Afghanistan and Iraq. In reality, American resources were insufficient, and prioritizing Iraq destroyed what hope there was for victory in Afghanistan.

(James Baresel)

Entrances and Exits, by Michael Richards (Permuted Press; 440 pp., $35.00). An episode of Jerry Seinfeld’s Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee featuring Michael Richards includes the following exchange:

Richards: “Thanks for sticking by me.”

Seinfeld: “There was no issue with that.”

Richards: “Well, it meant a lot to me. But inside, it still kicks me around a bit.”

Seinfeld: “That’s up to you to say, ‘You know, I’ve been carrying this bag long enough. I’m gonna put it down.’”

Of course, they are talking about the only thing Richards is known for by those too young to have made his brilliant Seinfeld character Kramer part of their vocabulary of celebrity in the 1990s. It is the night he was recorded on stage saying a particular word that it has been determined white people (but not black people) must be utterly ruined for saying.

Richards discusses the episode in only one brief chapter of his autobiography, but its presence looms over the entirety. He still feels as though he did something unforgivable. His personality is highly self-critical, which, properly limited, is a positive trait. It is certainly what enabled Richards to craft his comedic art to such a polished state. But in our inquisitorial/confessional moral culture, it is nothing more than a massive weak point to be exploited.

What, after all, did Richards do? He was doing his stand-up act at the Laugh Factory in Hollywood and got irate when a large and noisy group disrupted his performance. They responded by insulting him and continued their disruptive antics. Richards returned the insults, endeavoring as comics do to blend the taming of hecklers into his comedic routine. The rhetorical game escalated. Every stand-up comic knows you cannot lose to hecklers. Richards made cracks about slavery and Jim Crow punctuated by the word that cannot be said. And in a flash, his career was over.

On the Today Show a few days later, two of the men who had exchanged insults with Richards, encouraged by a spectacularly stupid attorney, suggested that he might need to cough up reparations for the irreparable harm he had inflicted on them. Reparations… for saying a word.

In the last minutes of the Comedians in Cars episode, Seinfeld tells Richards, “Well, I hope that you do consider using your instrument again because it’s the most beautiful instrument I’ve ever seen.” I share that hope.

(Alexander Riley)

Leave a Reply