Englishness may be coming back into fashion. After the union of the English and Scottish crowns and the foundation of modern Britain in 1603, the idea of Englishness was increasingly submerged in, and confused with, the idea of Britishness. It now looks as if the English may be becoming self-conscious again. Three centuries of outward-looking expansionism are being succeeded by a new mood of introspection.

The empire has gone, leaving only the purposeless Commonwealth. Scottish and Welsh devolution has left behind the running sore of the “West Lothian Question.” This partial evisceration is to be followed—if the government has its way—by the division of England into regional assemblies that would not only obviate the need for England’s traditional parish and county councils but undermine the whole concept of England as a unitary territory. As well as losing powers to the devolved parliaments and (soon) the regional assemblies, Britain’s parliament at Westminster has also handed over many of its prerogatives to Brussels, with a corresponding loss of prestige. Since 1948, large-scale immigration (almost all of it to England) has been taking place, and the idea of being British has been diluted so much that it is increasingly meaningless. When viewed in conjunction with the above phenomena, the fact that the tercentenary of the union of the crowns passed almost without official or public notice suggests that the Great Britain “brand” is on the wane. Increasingly, Great Britain is no longer a land but just an island—no longer a home, just a house.

Small wonder, then, that some of England’s cleverest sons and daughters shouldhave once again begun to wonder what it is to be English, despite official disapproval. Labour’s attitude was well summed up by Jack Straw several years ago, when he opined that the English had long been an especially violent and lawless people and that English nationalism therefore needed to be repressed (a perspective shared by the Conservative leader at the time, who spoke about how “dangerous” English nationalism was, or could be).

Part of this official disapproval may be attributed to the widespread belief that nationalism is no longer “relevant.” More may be an expression of the bruised vanity of the political class, which does not like the wounding inference that many people do not actually like the country that politicians have created and fostered. It is also likely that they do not relish the prospect of being sidelined in a political future that they will not be able to control. But essentially, they believe their own dark propaganda and really do think that Englishness equals evil. As always, the “official” view is somewhat out of kilter with the views of many, perhaps most, ordinary people. While they look upon English self-consciousness as a kind of xenophobia, surely it is the English political class’s own “synophobia” that is the really interesting psychological problem.

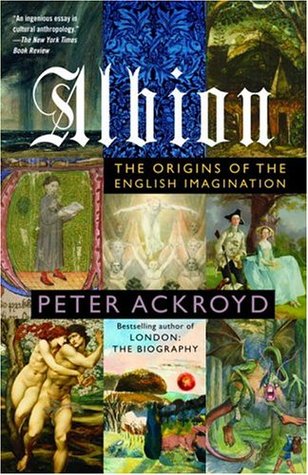

An embarrassing silence had grown up around the whole concept of being English. Enter Peter Ackroyd, who, like an English Luigi Barzini, has come to fix the intellectual underpinnings for a newly resurgent Englishness—albeit an Englishness born of fear rather than hope, a necessary defensive measure rather than a bold assertion. (As Ackroyd notes in another, more specific context, “A sense of mortality, or of dwindling numbers, may . . . encourage a sense of identity, threatened or otherwise.”) For such an influential writer as Peter Ackroyd to write a book like Albion is hugely significant of the changing mood in England. English nationalism may be just about to become middle class—ergo, respectable.

Ackroyd has long concerned himself with English faces and places. As well as his voluminous journalism, and his outstanding London: The Biography, he has written biographies of Dickens, T.S. Eliot, Thomas More, and William Blake. Characters in his award-winning novels have included architect Nicholas Hawksmoor (whom he memorably cast as a murderous mystic who erected his buildings according to cabalistic lore), Oscar Wilde, John Milton, William Hogarth, William Byrd, and Tobias Smollett, among many others. Despite an element of camp in some of his writings, his is an original and authoritative voice. Now, he has put all of his vast reading, his literary training, and his superlative writing skills (“the language that speaks of decay falls back into its original patterns, like the countenances of those about to die”) to use in a quixotic attempt to rescue Englishness from extinction.

Albion is full of glittering gems of lore and tradition, and gossamer-seeming intimations that, when examined, turn out be stronger than they first appear—spider silk rather than cotton thread. Even when Ackroyd is being fanciful, he is pleasing and provocative: “It may be that those who live upon a small island take a delight in small things,” he says, to launch a discussion on the art of the miniature, a distinctively English form. This is admittedly a forced apercu, but it is certainly arguable. Rather more forced is

This desire to miniaturise obsessions . . . could . . . possibly be related to the pattern of English detective stories in the twentieth century, when evil and murderous wickedness were seen to operate in small and cosy country villages.

There must be a unique sensibility within a nation that has maintained her original borders over so many centuries and which, until recently, had endured no important immigration since the Normans. Yet, as is so often the case when describing alleged national traits, Englishness is easier to recognize than to define.

In Albion, as with all group studies, there are innumerable gray areas and problems of categorization, as individuals’ characteristics move in and out of focus vis-à-vis corporate characteristics, and the group gradates into other groups. How does one define Englishness, so as to make it simultaneously flexible enough to allow evolution and rigid enough to have meaning? To make definitions still more difficult, Ackroyd claims that the “mixing or blurring of forms” is itself characteristic of Englishness. There is also the central paradox, as expressed so perfectly by William Vaughan in his 1999 British Painting: “The more local and specific a sensibility, the more it may aspire to universality.” As all men share certain characteristics, there are bound to be areas of overlap among narrower national categories and individual exceptions to every racial rule. Ackroyd is aware of the problem: “If there is such a thing as a native cast of thought it can properly be understood only in the context of a broadly European sensibility,” while “certain qualities defined here as peculiarly English are not uniquely so.”

Thankfully, Ackroyd is alive to the nuances and apparent contradictions and accordingly subtle in his suggestions and definitions. He says repeatedly that one of the hallmarks of the English imagination is “its willingness to adapt and to adopt other influences.” He believes, surely correctly, that the English imagination is the product of a blend of Celtic and Anglo-Saxon genes and influences. He notes approvingly Matthew Arnold’s suggestion (made in 1867) that this fusion has been productive of “a kind of awkwardness or embarrassment—a tendency to understatement—in the characteristic productions of England.” Correctly also, Ackroyd has co-opted the Vikings and Normans into Englishness—although he may be claiming too much when he says, for instance, that Durham Cathedral is a product of Anglo-Saxon, rather than Norman, cultural influences.

The question of how much Norman culture penetrated into Anglo-Saxon culture—or, for that matter, how much the Romans affected the indigenous tribes—is still a subject of hot dispute among historians. For much of her history, England has been less exposed to outside influences than many other European countries. England was at the very edge of the Roman world and no more affected by the Vikings than many other Northern European countries. For hundreds of years after the Norman invasion, the country lay at the periphery of European civilization; even after England’s rise to greatness under the Tudors, continental cultural currents caught on late here and arguably did not penetrate as deeply.

The methods are less important than the matter, however, and the best gauge of this book’s success is how true to life Ackroyd’s selected English qualities seem. So let us look at some of the common traits Ackroyd detects running through the long tale of England, many of which, of course, were transplanted wholesale to the New World—where, just as some Elizabethan English terms have survived in American English, they may yet persist in purer form.

Certain of these are more widely accepted as being “English” than others. For example, surely both “delight in the strange and occluded” and “love of the marvellous” are shared by many peoples. Ackroyd is on surer ground when he lists as classically English characteristics individualism, eccentricity, pragmatism, innate egalitarianism, understatement, plainness of speech, antiquarianism, irony, bawdy comedy, an obsession with death and decay, a preference for amateurism over professionalism, worrying about the weather, literary sentimentalism, love of gardening, a tendency to “consider matters in sequence rather than in system,” a “synthetic” rather than an analytic imagination, and, in religion, a fondness for instruction over theology. These examples ring true and therefore suggest that, after all, there is such a thing as Englishness, however difficult to define.

One paradoxical problem is that Ackroyd knows too much literary theory. He has blended genres together, not because he does not know the differences among them, but because “In England history has always been considered a manifestation of literature rather than scholarship” and because he likes the idea of synthesizing other people’s ideas, in the classic English manner. In other words, Ackroyd is too conscious of what he is doing—although perhaps self-consciousness is inevitable after decades of anti-English demystification. Also slightly grating are his frequent attempts to attach Englishness specifically to Roman Catholicism, as when he writes that “It is important to see how a predominantly Catholic culture and sensibility may still dwell within [the English imagination].” While Ackroyd is probably correct here, his agenda is rather too obvious.

Most regrettably of all, Ackroyd declines to discuss the effects recent political developments have had on England and the English. He seems instinctively to be against many modern leftists, because of his distrust for theories and systems, and is opposed to such presently fashionable notions as that England should have a written constitution. One could not see him as a Thatcherite Conservative, either. (No one who favors, as he does, “smallness, heterogeneity and temperate accommodation” could ever be sympathetic to socialist schemes, free-market reductionism, or political correctness.) It would have been especially interesting, however, to have learned his views on the newly arrived, non-Northern European influences that are having such an impact today in England’s cities. Ackroyd actually implies that this is not a phenomenon of importance when he writes that “Englishness is the principle of appropriation. It relies upon constant immigration, of peoples or ideas or styles, in order to survive”—a pleasing sentiment in Matthew Arnold’s days, when there had been no mass immigration since 1066, but clearly outdated now. Ackroyd knows that “The idea of a close-knit community . . . is central to the English imagination,” but he does not accept that close-knit communities can only exist within very specific cultural contexts. He insists that Englishness is about “placism, as an antidote to racism.” He does not seem to consider that races shape places, and vice versa, nor does he realize that every civilization has a tipping point beyond which it is inundated rather than influenced.

Nevertheless, all who love England should be grateful to Peter Ackroyd for his pioneering navigational efforts—his own “fantastic travel writing” around the too-little-visited shores of Albion.

[Albion: The Origins of the English Imagination, by Peter Ackroyd (Chatto & Windus) 516 pp., £25]

Leave a Reply