“The blood of the martyrs is the seed of the church.”

—Tertullian

The spread of Christianity was marked by a trail of blood, shed by myriad martyrs during the first three centuries of the Christian era. Another trail of blood followed: that of the Christian defenders of the Roman Empire, shed by Arabian Muslims in the course of their conquest of Syria, Palestine, Egypt, North Africa, and Spain. (A similar bloody path was left by the Arabs in the East, when they conquered and destroyed the Persian empire of the Sassanids, where Zoroastrianism was the accepted religion.) The martyrs of the Christian Church were put to death for their confession of faith in Jesus Christ. The Muslims of our day claim martyrdom, too, but their “martyrs” kill themselves in terrorist attacks against Israeli citizens and, on September 11, against Americans and others.

Why do we distinguish Christian and Muslim martyrs? Haven’t Christians also killed for the Faith? What about the Crusades, the Jews and Muslims in Spain, and Cortés in Mexico? Christians have killed, sometimes atrociously, but there are fundamental distinctions, and it is essential not to overlook them. The Rev. Patrick Sookhdeo, a man of Pakistani descent who grew up a Muslim in Guyana before embracing Christianity, is now the director of the Institute for the Study of Islam and Christianity in London. In a talk given on January 13 in Fairfax County, Virginia, he stated, “In dealing with Islam, you have to tell the truth. And you have to meet it head on. It understands power and only power, and so you have to know how to exercise power.”

The air campaign in Afghanistan, begun by the United States with incidental Allied assistance and coordinated with the rebel Afghan Northern Alliance and other anti-Taliban Afghans, has shown that we have power—at least enough to suppress an unpopular regime in a small country. But we have not shown that we know the truth and are willing to tell it. One thing is certainly true: Both Christianity and Islam spread rather rapidly, but by different means.

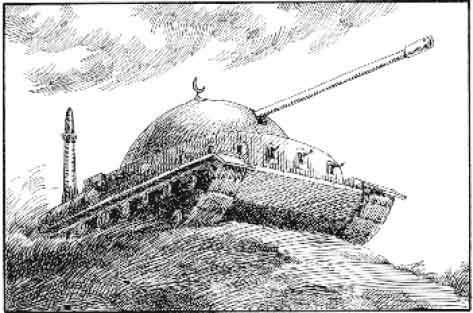

The difference in the means is suggested by the alacrity of the spread: Missionaries work more slowly than soldiers. From the beginning of Christian evangelism at Pentecost until the date when Christianity was spread throughout the Roman Empire and received toleration by the Emperor Constantine the Great (A.D. 313), over 250 years passed. Between the death of Muhammad in A.D. 632 and the Battle of Tours in northwest France, when the Muslim advance into Christian lands was finally stopped by Charles Martel, a century passed. In that century, Muslim control was extended over Syria, Palestine, Egypt, North Africa, Spain and the Roman-ruled part of Arabia, all once Christian lands (and, in addition, over the Persian empire in the East, which, unlike the Byzantine Empire, was totally crushed and disappeared from history).

Why did Muslim power spread so rapidly? Because of the use of the sword. Is Islam a religion of peace? There are certainly admonitions to peace in the Koran—as well as references to taking up the sword. The exhortations to wage war against non-Muslims are more explicit in the Hadith, the traditional interpretation of the Koran. One such statement reads: “O Allah! You know that there is nothing more beloved to me than to fight in your cause against those who disbelieved your Apostle and turned him out of Mecca.” Many of the exhortations are somewhat ambiguous with respect to the context (like this one), but from the conduct of the Arabs and their successors, it is evident that they were interpreted as giving high praise to fighting against unbelievers. You will look in vain in the New Testament for exhortations to take up the sword against unbelief; the word “sword” itself occurs only rarely, and never in a context where evangelists or missionaries are exhorted to use it. In fact, in the Garden of Gethsemane, Christ told St. Peter to put his sword away.

Again, to tell the truth, the Christian Church was spread over the course of the centuries by nonviolent missionaries and evangelists, and the truth of the Gospel was attested over and over again by the martyrdom of those who let their blood be shed for it. Islam was spread by conquest. As the Oxford History of Islam points out, “The spread of the [Muslim] empire was carried out mainly by armies, the spread of the Islamic faith beyond the caliphate’s border was usually the work of merchants and pious preachers . . . The main spreading of the Islamic community, however, took place within the caliphal empire itself.”

During the first three centuries of Christian expansion, persecution became so common that Georges Florovsky, the eminent Orthodox theologian, could write that, in that era, martyrdom was the normal Christian life. At first, the harassment came at the hands of Jewish religious authorities and targeted only Hellenistic Christians. By A.D. 51 or 52, the emperor Claudius (41-54), took notice of the conflict between Jews and Christians and expelled both “sects” from Rome.

Although Christians suffered under Nero (54-68) and Domitian (81-96), Trajan (98-117), the first of the four “good emperors,” formulated a policy that encouraged officials not to hunt Christians but to punish those who came to light and refused to abjure their allegiance to Christ. The fourth “good emperor,” Marcus Aurelius, a stoic philosopher, continued the persecutions: During his reign, Justin Martyr, a philosopher converted to Christianity, and Polycarp, the bishop of Smyrna who had been taught by Saint John the apostle, were executed. Finally, religious tolerance came in A.D. 313 after the conversion of the emperor Constantine. After that, by and large, the blood of martyrs was no longer shed in the Roman Empire. The spread of Christianity continued, largely by missionary work, but sometimes by a prudential decision on the part of a local ruler. In 380, the emperor Theodosius made Christianity the state religion and gradually eliminated the older pagan ceremonies. Pagan concepts and institutions survived for several decades, yet pagans were not persecuted. Plato’s Academy in Athens did not close until 529, the same year that St. Benedict established the monastery of Monte Cassino and the Benedictine order. By then, much of Europe had been overrun by the pagan Germans; the Roman armies retreated, but Christianity advanced. The conversion of the invading Goths had begun with the mission work of Ulfilas, a former slave, in the fourth century. The most powerful Germanic nation, the Franks, followed their king, Chlodovech (Clovis), converting to Christianity in A.D. 496. This was not a mere formal christening, for Clovis asked for the approval of the Thing (the assembly of army chiefs) and was required to study the comprehensive catechism of the early Church before receiving baptism.

The conversion of the Slavs was the work of missionaries, not warriors. The Slavic peoples of the south and east, who were filling up Greek territory depopulated by a plague, heard the Gospel not from Roman soldiers but from two Greek monks: Cyril and Methodius gave them the ancestor of today’s Cyrillic alphabet and a liturgy in what is now known as Old Church Slavonic. The last of the European peoples to accept Christianity were the Lithuanians, converted in 1386 when their Grand Duke Jagilas married the Polish Queen Jadwiga and joined their two countries in a personal union. Thus the Church that sprang up where so many martyrs shed their blood continued to expand by missionary witness or by marriage, sometimes attested by martyrdom—as when Boniface, an Anglo-Saxon missionary to the still-pagan Germans, was killed by the Frisians in 754—and, occasionally, by force, as when Charlemagne, king of the Franks and the first Holy Roman emperor, compelled the Germans east of the Rhine to accept baptism.

A dramatic change came in the 16th century when the Spanish conquistadors, some of them serious Catholics and interested in winning the Indians to Christ, first conquered them, plundered them, and in many cases made slaves of them, all in the context of bringing them the Gospel. But missionaries did not always follow conquerors. In the same century, Roman Catholic missionaries went to both Japan and China without being preceded or accompanied by military power. In subsequent centuries, Christian colonization in Africa and southern Asia was followed by missionary efforts, but the colonial powers did not push conversion and, in fact, often hindered the missions. Thus, by and large, the Christian Gospel was spread through missionary efforts, often at the cost of Christian blood, but rarely by shedding the blood of the unconverted.

Such was not the case with Islam. A map of Europe and the Near East in 630 shows that the entire Mediterranean shore, including Egypt, Asia Minor, Syria, and the northern part of the Arabian peninsula, belonged to the Christian Roman Empire. (Most of Mesopotamia and all of Persia, extending into modern Afghanistan, was Zoroastrian.) A century later, all of North Africa, most of Spain, and all of the Near East except for Byzantine Asia Minor—as well as all of Persia—were under Muslim rulers. In the century following the death of Muhammad, the Sassanid Empire of Persia was destroyed and the Byzantine Empire stripped of its African, Egyptian, and Syrian lands. Arab troops had reached Tours in northwest France before being defeated by Charles Martel. The Muslims had besieged Constantinople three times.

The inhabitants of conquered territories were gradually converted to Islam by, among other tools, the policy of taxing non-Muslims. Islamic law officially tolerated the other “peoples of the Book” (Jews and Christians), but it subjected them to taxation from which Muslims were exempt. Zoroastrians and adherents of other religions, on the other hand, were usually given the choice of conversion or execution.

The Christians fought back, and the Byzantine emperors Nicephorus II (963-969) and John I (969-976) regained some territory. After the disastrous Battle of Mantzikert in 1710 (in which the Muslim Turks gained control of most of Asia Minor, the heartland of the empire), the new emperor, Alexis I Comnenus (1081-1118), appealed to the West for aid. As historian Steven Runciman writes, “The Battle of Mantzikert was the worst disaster to befall Byzantium; and it was the indirect cause of the Crusades.” Those who reflexively condemn the Crusades should be reminded that they began as a response to Muslim conquests.

After the failure of the Crusades, Islam resumed its westward expansion by military force, eventually conquering Constantinople and putting an end to the Byzantine Empire in 1453. Hagia Sophia, then the largest church in Christendom, was converted into a mosque. In Spain, however, the Muslims were finally expelled in 1492, the same year that Christopher Columbus crossed the Atlantic and discovered America. In 1992, political correctness ensured that the 500th anniversary of both events, in Europe and America, garnered more criticism than celebration.

In the decades following 1492, the Turks launched repeated assaults from their new base in Constantinople. In 1526, a Turkish force overwhelmed the Hungarians and Bohemians at the Battle of Mohacs. Three years later, the Turks besieged Vienna. A century-and-a-half later, another massive Muslim push took place. By September 11, 1683, the Turkish janissaries stood but a few hundred meters from the Viennese imperial place. That day, a Polish relief army led by King John Sobieski arrived on the Kahlenberg above Vienna, raising to 70,000 the number of Christian allies trying to lift the siege by 115,000 Turks. The next day, the Poles, Germans, and other allies handed the larger Turkish army a disastrous defeat.

This ended the Turkish advance into Europe for three centuries, until, in 1995, the Turks of Bosnia (the Serbs use this term for the ethnic Slavs of Bosnia-Herzegovina who had embraced Islam during the Turkish rule), aided by the United States, established the first new Muslim state in Europe. In 2001, a second Muslim state was born in all but name in Kosovo, again through the application of U.S. military force. President Clinton, it is said, wished for a legacy. Perhaps his most significant accomplishment will be to have begun the Muslim reconquest of Europe.

As we know all too well, on September 11, 2001, Muslim terrorists devastated two sites in the previously untouched United States. In retaliation, the terrorists’ stronghold in Afghanistan has been destroyed, and the country has a new government, which is currently on friendly terms with the United States. President Bush has successfully led us in the war, as he calls it, all the while praising Islam and telling the American people to reject the idea that there is any inherent connection between the religion of Muslims and the acts of the terrorists.

Voices of warning are stifled. The Reverend Sookhdeo notes that, when he was one of the few to criticize a 16-page supplement in the Daily Telegraph praising Islam, “I was simply massacred. The only line permitted is that Islam is peace, it is tolerant, it is a wonderful religion . . . We have sold a lie, and the people have bought it.”

It is all but impossible for Christian missionaries to enter Muslim-ruled countries, and when foreign or local Christians in a Muslim land seek to evangelize, the prescribed penalty is usually death. If someone converts, death will be his fate. This violates the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of the United Nations, to which all Muslim countries belong. They simply ignore the declaration, and the West silently acquiesces. Criticism would be intolerant.

In virtually every part of the world where a Muslim-ruled state or territory impinges on a state with a Christian or other non-Islamic population, there is almost always bloody conflict, usually perpetrated by Muslims against non-Muslims. Under Soviet totalitarianism, the Muslim elements of the Russian Federation as well as of the Central Asian republics of the Soviet Union were largely kept in check; the same was true of the Muslim population of Sinkiang in western China. With the Soviet Union gone, Christians and other non-Muslims have, once again, suffered at the hands of their Islamic rulers.

Muslim aggression is supported in varying degrees by wealthy Muslim societies in the Near East. In parts of Indonesia, Muslims have launched repeated armed assaults against Christian populations. Nigeria, once seen as the former British colony most likely to prosper after achieving independence, is now torn apart by the determination of the dominant Muslim party of the north to impose sharia. Before September 11, hardly any attention was given to the suffering of Christians in Nigeria, or in Somalia and the Sudan, where Muslim-inspired civil war has caused over two million deaths in the last 25 years. Even before the American establishment’s love affair with Islam began after September 11, Muslim assaults on Christians went largely unnoticed. In much of Europe and increasingly in the United States, Muslim communities aggressively undermine every effort even to understand what has been done in the name of Islam, not to mention efforts to restrain it.

The United States have demonstrated that we have power—at least enough to defeat Taliban ground forces numbering about 40,000. What we have not demonstrated is that we understand what is at stake or that we understand the truth. The only alternative explanation for this lack of understanding is cowardice. As Jean Maisonneuve wrote, tolerance toward people is a variety of magnanimity, a virtue; but tolerance toward positions known to be false is cowardice, a lie, a crime.

Leave a Reply