If you are looking for literary reflections or information about the intentions of the author of Red Harvest, The Maltese Falcon, and The Class Key, forget about it. There is precious little of that in Dasthell Hammett’s letters. If you are looking for insight into the character of the enigmatic Dasthell Hammett, you won’t find much of that, either. And if you are looking for a good read—wit, writing, truths—then you will find the letters of Dasthell Hammett about two egg rolls short of a pu pu platter.

These letters are mostly innocuous— gossipy, affectionate, sometimes ruefully funny. But there is no spark that can kindle them into something beyond themselves. Hammett seems to have been happy only in some sort of martyrdom, joining the Army again at the age of 48 and serving mostly as a journalist in the Aleutians, or going to jail because he bucked authority during the McCarthy episode. His is a sad story, mostly about boredom and writer’s block and alcoholism and sexual chaos, but nothing makes it an interesting one. Actually, it is when Hammett himself is most interested that he is most boring. What else would you expect from a communist? Ideology of his sort required a lobotomy of a kind, and that self-inflicted wound may be what killed him as a writer.

Sure, a writer can write badly sometimes, but there are some aberrations that indicate not only a tin ear, but a tin brain. Hammett’s sermonettes on Marxism, addressed to his daughter, Mary, are appalling in themselves and, as instruction to the young, disgusting—rather like the banal letters of the Rosenbergs. The combination of willed stupidity and smarmy complacency is utterly repellent:

Our aid to Russia is still being slowed up by pressure of the Catholic Church, but Roosevelt’s quotation from the Soviet Constitution yesterday to show that they have the same sort of religious freedom as we may do some good there. It at least shows that he hasn’t yet knuckled under to the church as he did during the Spanish Revolution [October 1, 1941].

When was the last time you saw that many fallacies in two sentences? George Orwell suggested that anyone who could write such piffle was a party hack and no writer at all. Only a decade before, Hammett had immortalized himself; now, he sounded like a crude propagandist. The story is notable, but that doesn’t make reading it rewarding.

On the other hand, reading Chandler is always rewarding, not so much for what he says as for the way he says it. Chandler was a writer with his own sound, his own rhythm and phrasing. His letters are so much fun that I have sometimes thought that they are his best pages. Chandler’s letters have been gathered before, in Raymond Chandler Speaking (1962 and 1977), more extensively in MacShane’s Selected Letters (1981), and sparsely in a Library of America edition (1995). Early works were gathered in Bruccoli’s Chandler Before Marlowe (1973), still others in MacShane’s The Notebooks of Raymond Chandler and English Summer by Raymond Chandler (1976). What we have here is a thinned-out version of the 1981 collection with some additions, such as Chandler’s hitherto unpublished piece on Lucky Luciano, that do not represent the author at his best. To have all the Chandler there is, you need to have all the books cited. So there is a sense in which this latest collection is a disappointment.

But there is another sense—the sense of reading itself—in which this collection is delightful. Nothing else quite compares to Chandler on a riff: He knows how to build the rhythm and get to a climax.

Television is really what we’ve been looking for all our lives. It took a certain amount of effort to go to the movies. Somebody had to stay with the kids. You had to get the car out of the garage. That was hard work. And you had to drive and park. Sometimes you had to walk as far as half a block to the theater. Then people with big fat heads would sit in front of you and make you neryous. . . Radio was a lot better, but there wasn’t anything to look at. Your gaze wandered around the room and you might start thinking of other things—things you didn’t want to think about. You had to use a little imagination to build yourself a picture of what was going on just by the sound. But television’s perfect. You turn a few knobs and lean back and drain your mind of all thought. And there you are watching the bubbles in the primeval ooze. You don’t have to concentrate. You don’t have to react. You don’t have to remember. You don’t miss your brain because you don’t need it. Your heart and liver and lungs continue to function normally. Apart from that all is peace and quiet. You are in poor man’s nirvana. And if some nasty-minded person comes along and says you look more like a fly on a can of garbage, pay him no mind . . . just who should one be mad at anyway? Did you think the advertising agencies created vulgarity and the moronic mind that accepts it? To me television is just one more facet of that considerable segment of our civilization that never had any standard but the soft buck [November 22, 1950].

Right. And as long as Raymond Chandler makes with what he called the “magic” and the “music,” he will always have an audience. Chandler respected what Hammett had accomplished in fiction, but he wouldn’t have liked his letters any better than they deserve.

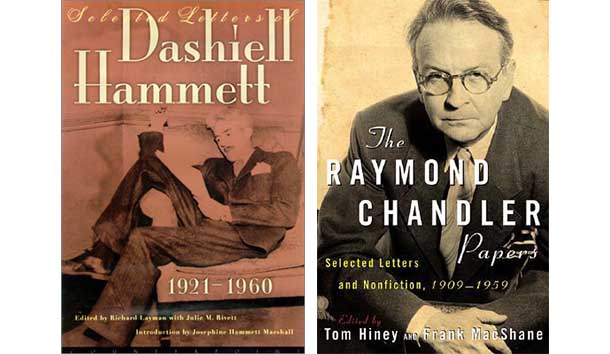

[Selected Letters of Dasthell Hanimett, 1921-1960, edited by Richard Layman with Julie Rivett (Washington, D.C.: Counterpoint) (672 pp., $40.00]

[The Raymond Chandler Papers: Selected Letters and Nonfiction, 1909-1959, edited by Tom Hiney and Frank MacShane (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press) 267 pp., $25.00]

Leave a Reply