“The thing is to squeeze the last drop out of the medium you have learned to use. The aim is not essentially different from the aim of Greek tragedy, but we are dealing with a public that is only semi-literate and we have to make an art out of a language they can understand.”

—Raymond Chandler

These two volumes of crime novels, bound and printed as classics, challenge our notion of the American canon. Or perhaps they simply remind us of what we were actually reading when we were supposed to be reading something else. If reading is good for you, bad reading is even better.

To put it another way, our Pleiade has become a Serie Noire. It was ever thus. In the British tradition, of course, there was that scandalous background extending from Robert Greene’s pamphlets on coney-catching to Defoe’s Moll Flanders and Fielding’s Jonathan Wilde, and on to the Gothic novel, the Newgate novel, Oliver Twist and The Moonstone, and the early Greene. The French tradition, meantime, offers an extended parallel in criminal fiction. In Balzac, Stendhal, Zola, and Camus, we ratchet the guillotine. Dostoyevsky’s ax murderer was possibly redeemed, but not before he was a very bad boy indeed. Here in Hicksville, we have our own distinctive tradition of rough stuff. Poe, Hawthorne, and Melville limned the metaphysics of transgression in ways that have immortalized their names. They left upon the vectors of crime a stink of intellect—a Limburger of cerebration. The other tradition is the vulgar one, the most notable practitioner of which was George Lippard. But we must not forget in our puritanical/ sentimental way, that Huckleberry Finn himself was a notable juvenile delinquent. Louisa May Alcott, who made nice in Little Women and Little Men and Under the Lilacs, also scribbled subversive melodramas on the side. American innocence has always been related to violence. Billy Budd was, we tend to forget, technically guilty. Where else but in America would Truman Capote, of all people, have written In Cold Blood? Leslie Fiedler and Norman Mailer are not the only Americans who have understood a relation between Captain Ahab and Charles Manson. Mark Twain and Ernest Hemingway, perhaps more than any others, connected the American traditions of Gothic terror to the authentic voice of our own speech.

Thus the stage was set for the crime novel as a work of art in the vein of the “lyrical novel” as we have known it—the best tradition of American fiction. So the question about these crime novels is not whether they are criminal enough, but whether they are sufficiently novels. Are they, after all, literature? Not all of them were published as paperback originals, though we may remember them that way. Geoffrey O’Brien’s Hardboiled America reminds us of the glory days of paperbacks back in the late 40’s and 50’s, when Faulkner’s and Steinbeck’s books looked like Cornell Woolrich’s. You may perhaps remember those lurid covers, icons of American art—unmade beds, whiskey bottles, lots of underwear, sometimes a handgun—which somehow said more to me than any other images of books ever did. And yet it is not hard to see many of the crime novels as moral fables. These narrations are defined by crime, but they are as wholesome as Sunday School lessons. Crime doesn’t pay. That’s a point that was made by Allen Tate in testimony about the contested publication of Hubert Selby, Jr.’s Last Exit to Brooklyn. Buying sleaze and looking down a blue nose, the American public has been confused about this point since the days of Cotton Mather, and still is.

Volume one of these crime stories is much the better of the two, boasting several classics. These were the books that people actually read for pleasure instead of duty, and then declared that they had really loved The Golden Bowl. Yet Stephen Crane and Jack London showed us something about the lower depths, and Hemingway’s story “The Killers” implied much that would be developed by others. To Have and Have Not is Hemingway imitating his imitators, and writing a left-wing crime novel himself Faulkner had his innings in Sanctuary, one of his best books. The Great Gatsby was first filmed in 1949 as a sentimental gangster movie, which was an oddly fitting approach. Robert Penn Warren’s All the King’s Men seemed to me to owe something of its plot to Dashiell Hammett’s The Glass Key, and tonal inflections to Raymond Chandler. So if American literature has so often been the crime novel, then the crime novel is American literature, as these collections deliberately suggest.

If these novels are not to be confused with the lurid covers of fond memory, then neither are they to be confused with the movies derived from them. James M. Cain’s The Postman Always Rings Twice (1934) was filmed twice, but readers will find his Cora to be no Lana Turner. Horace McCoy’s They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? (1935) was at last filmed in 1969, and faithfully too; yet that version is lacking in impact. Edward Anderson’s Thieves Like Us (1937) was also filmed many years out of context (1974), Kenneth Fearing’s The Big Clock (1946) effectively done in 1948, William Lindsay Gresham’s Nightmare Alley (1946) rather well treated the next year, and so on. These facts may remind us of some good and some not so good films; also, perhaps, that just as great novels don’t make great films, lesser novels too may be superior to the films derived from them.

In looking again at The Postman Always Rings Twice, we would do well to recall that Albert Camus used the novel as a model for L’Etranger. I think we would also have to say that some aspects of Cain’s book have not worn well. “I bit her. I sank my teeth into her lips so deep I could feel the blood spurt into my mouth. It was running down her neck when I carried her upstairs” (end of Chapter Two). Why does the narrator sound more like Count Dracula than a blue-collar lover boy? However, Cain’s story of a descent into hell and even of a kind of redemption in death has powerful drive, a highly appealing idiomatic simplicity, and enough irony for a Greek tragedian. Nick Papadakis is “greasy,” but I think Nick is a Greek because Cain wanted to write the melodrama as Greek tragedy. Camus was hooked by Cain because Frank is executed for killing Cora Papadakis, which he didn’t do, and not for killing Nick, which they did. Camus remembered the swimming scene for his novel, but in Cain that scene leads to a sentimental swerve towards married love, cut short by fate. Treated contemptuously by Edmund Wilson and Joyce Carol Gates, Cain was some kind of a writer nevertheless. The Postman Always Rings Twice has power, form, irony, and verbal resource. It is hard to know what more we can ask for than that, and I am glad I read the old thing again. I couldn’t put it down. I was reminded of the first time I read that sleazy moral fable 40 years ago. Good writer, James M. Cain. Doesn’t waste your time with the fancy stuff.

They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?, Horace McCoy’s first novel, is a masterpiece that was recognized by the French more than half a century ago; his novels remain in print in French, though not in English. This republication is therefore doubly welcome. They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?, with its typographical experimentation and expressive collision of form and idioms, juxtaposing the language of the judge’s sentence with Robert’s narrative, is a landmark of modernist penetration into popular literature. Horace McCoy became a Hollywood hack, but at least once he roused himself to prove he deserved his French reputation. Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye (1948) is his attempt to write a gangster story as the Great American Novel, and it too deserves to be revived. To think of McCoy in Paris, receiving his recognition before he died of a heart attack at the age of 58, is to reflect that sometimes justice really is served.

If Horace McCoy’s “objective lyricism” and formal disposition has power, Edward Anderson’s discourse has beauty. Thieves Like Us is a masterpiece of writing and should be used in creative writing classes as a model of dictional purity and the limited third person point of view. Thieves Like Us was in fact based on interviews Anderson conducted with his cousin Roy Johnson, who was serving a life sentence for armed robbery. Filmed twice, the novel was cited by Raymond Chandler for its forgotten greatness, and we can see why. The gritty and doom-laden tale heads where it inevitably must as the stick-up artists fend off the fate they provoke. When a self-serving criminal declares of the bankers, “They’re Thieves Like Us,” we might recall that even with computerized systems banks now take longer to clear a check than ever before. They get their float, and guess who from. The left-wing view of capitalism has a legitimate populist, not a Marxist, base.

The poet Kenneth Fearing, author of The Big Clock, once told the FBI he was “not yet” a member of the Communist Party. The Big Clock is set in the world of big-time corporate publishing in a way that seems oddly contemporary. Its varied narrators break up the point of view, but I think the prose is the least distinctive in this volume. William Lindsay Gresham’s Nightmare Alley, however, is something else. Gresham himself was a communist who served as a medic in the Lincoln Brigade. He later converted to Presbyterianism and then to Zen Buddhism, the occult, and Dianetics. He struggled with alcoholism and committed suicide in 1962. But Nightmare Alley is not a confused work, though one passage, in Chapter XIX, is almost pure Popular Front agitprop. Nightmare Alley is not so much a lyrical novel as a restricted epic. The world of the carnival is presented as a trope, an image of society, not unlike the Pequod. Stanton Carlisle learns “the secret” of deception and manipulation and goes from being a lowly huckster to a classy con man. Nothing is better than the “Reverend” Carlisle’s spurious sanctimony as he bilks the pigeons whom he deceives with phony seances. Stan Carlisle crashes because he runs into a deceiver more ruthless than he, and winds up as the lowest of the low: a geek who bites the heads off chickens at a carny. Nightmare Alley is remarkable for its range, its Tarot card symbolism, and its elaboration of the image of the magus as the ultimate con man—an image indeed of all kinds of mystification, including religion, advertising, big business, and society in general. The self-possessed Stan is inside a mess of anxiety. The novel is Freudian as well as Marxist, and a tour-de-force of sleaze. Its strength is its bid for Great American Novel status. Its weakness is probably some failures of language or hasty execution. Even so. Nightmare Alley is an infernal tour of evil with grim national implications for its time and for today. As a feat of writing, this novel, like the others, must make us wonder where this kind of gutsy engagement went to when it disappeared from the publishing scene.

The case of Cornell Woolrich must also give us pause. In his eccentricity— he was a virtual writing machine who lived with his mother in a hotel in New York City for 25 years—he offers as indelible an image of the American writer as Edgar Allan Poe or Emily Dickinson. Woolrich, a.k.a. William Irish and George Hopley, was a fountain of material for pulp magazines, paperback originals, film, and television. He was not so much a gifted writer as something else—a tormented wordspinner with a flair for melodrama, I Married a Dead Man (1948), filmed as No Man of Her Own, had its genesis in a story, “They Call Me Patrice,” originally published in Today’s Woman (April 1946). The provenance explains something about the cornball prose and hysterical atmosphere, the Mary Roberts Rinehart “Had I but known!” qualities, but does not explain why this meretricious exercise should be so compelling. Woolrich does indeed rise to a kind of poetry in the suffocating tale of impersonation and murder. The Greeks have their Homer, we have this: “Life was such a crazy thing, life was such a freak. A man was dead. A love was blasted into nothingness. But a cigarette still sent up smoke in a dish. And an ice cube still hovered unmelted in a highball glass. The things you wanted to last, they didn’t; the things it didn’t matter about, they hung on forever.”

Volume two, American Noir of the 1950’s, is not nearly as compelling or compulsory as the first volume. The presence of Jim Thompson’s The Killer Inside Me (1952) must nevertheless be noted. This first person narrative from beyond the grave (like Cain’s) is a trip through the hellish mind of a sociopath or paranoid schizophrenic who has diagnosed his own childhood trauma. Disguised as a cliche-spouting deputy sheriff in a Texas town, the lethally deceptive killer grabs the reader by the lapels and won’t let go. He knows it, too.

In lots of books I read, the writer seems to go haywire every time he reaches a high point. He’ll start leaving out punctuation and running his words together and babble about stars flashing and sinking into a deep, dreamless sea. And you can’t figure out whether the hero’s laying his girl or a cornerstone. I guess that kind of crap is supposed to be pretty deep stuff—a lot of the book reviewers eat it up, I notice. But the way I see it is, the writer is too goddamm lazy to do his job. And I’m not lazy, whatever else I am. I’ll tell you everything.

A killer itself, written in four weeks as a paperback original, The Killer Inside Me is by far the finest work in the second volume. Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mr. Ripley (1955) was the basis for a fine film, Rene Clement’s Purple Noon, in which the sociopathic chameleon and killer gets his at the end. But the point of Highsmith’s book is that the talented Tom Ripley gets away with everything. On the prowl in Europe, this American is far from innocent as he lies, and forges, and impersonates, and kills. I noticed at the beginning that Ripley had been asked by the parents of a weak American artist to persuade their son to come home from Italy, and thought of the similarity to the initial situation of James’s The Ambassadors. Sure enough, as Ripley sails for Europe, a James novel is recommended to him (Chapter Three) and is then specified (Chapter Six) as The Ambassadors. Highsmith’s witty reversal of James’s international theme was in some way related to her own life as an expatriate writer in Europe.

The theme of the artist is repeated in Charles Willeford’s Pick-up (1955) and David Goodis’s Down There (1956), though in neither case is it convincingly displayed. I don’t find that these novels are written on a plane comparable to those I have cited. And Chester Hines’ The Real Cool Killers (1959) seems to me to be pulp fiction without redeeming elements. Telegraphic one-sentence paragraphs do not a discourse make, or at least not here. We may note, however, that Chester Hines actually served time for armed robbery.

So what do we have besides a lot of terrific books to read? Behind the literary considerations, there is much. It is chastening to read in these authors’ backgrounds of broken homes and divorces, alcoholism, political radicalism, and—in at least two cases—sexual deviation. If that changes our cozy image of what a writer is, so much the better. In terms of the myth behind the tales, the overarching theme is a perception of the social lie, the fraud of bourgeois propriety that masks a monstrosity of manipulation, lust, and violence. Cain’s Cora Papadakis wanted middle-class respectability. Highsmith’s Tom Ripley succeeded in becoming an elegant, continental gentleman. Gresham’s Stan Carlisle became a pious spiritualist who preyed upon the guilt of the wealthy. It is not a pretty picture of America, but neither is it a false one. The shamelessness of politicians, lawyers, and corporate leaders, in inverse relation to their sanctimony, is enough to provoke—if not to justify— any response you care to mention. The worst would be to become not a criminal but a sleek fraud who uses the veneer of civility to hide an irresponsible depravity. Shakespeare and Dickens, those popular authors, knew that very well. So do Hollywood, Madison Avenue, and, deep down, the White House.

Cain and McCoy and Anderson and Gresham and others have not only written better than many “respectable” middle- brow novelists (and many pain-in-the-neck highbrows as well), but they have shown more about our national psychology and sociology. Such unpleasant truths are actually a ground for recovery—homeopathic medicines that are, finally, wholesome.

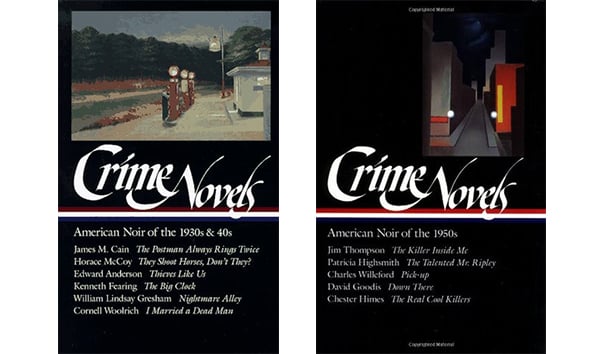

[Crime Novels: American Noir of the 1930s and 40s, edited by Robert Polito (New York: The Library of America) 990 pp., $35.00]

[Crime Novels: American Noir of the 1950s, edited by Robert Polito (New York: The Library of America) 892 pp., $35.00]

Leave a Reply