A wit and a fussbudget as well as a scholar, Paul Fussell is one of the best essayists and observers around. For personal as well as literary reasons, there is no one better qualified to undertake a study of the writings of Sir Kingsley Amis. They make a natural pair. Indeed, they have been friends for some years, though that very relationship may have something to do with the flaws in Fussell’s study of Amis’s books and mind.

Fussell has pointedly excluded Amis’s best known productions, his novels. He wants to show us Amis as a man of letters, a poet, a critic, an essayist, an academic, an anthologist, a traveler, an explorer of the good life—and on the whole, this strategy is effective. After all, there is something to be said for a man who wrote On Drink, Every Day Drinking and How’s Your Glass?, and Fussell says it. There is something to be said, too, for the editor of The Golden Age of Science Fiction, The New Oxford Book of Light Verse, The Faber Popular Reciter, and the author of books on science fiction, James Bond, and Rudyard Kipling. Fussell sees Amis as a moralist, an upholder of standards, an accessible craftsman, and a civic writer. He also sees him as a good poet, faithful to his calling, whose verses fill some of the vacuum left by the inroads of modernism and the collapse of culture in the sense in which it was known not so long ago. And in making these points, Fussell is quite successful.

What is neither successful nor sound, however, is Paul Fussell’s critical acumen. Perhaps he became so caught up in the celebration that the celebration got scanted, which is odd for him. Since he does not say so, perhaps this is the place to say that not every thought that has emerged from the Amis font has been a worthy one. The sins of youth, such as Amis’s sneering at Beowulf, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, and Jane Austen, seem now more dim-witted than naughty, and the goofy repetition of these embarrassments lends dignity to neither party. Furthermore, Fussell has so collapsed the distinction between the man and the writer that even as he insists on Amis’s moral earnestness, he repeats passages in which Amis spitefully insulted people about private matters. The only mistake Fussell attributes to Amis is his support of NATO during the Cold War. With a friend like this—who repeats bad jokes that only worked the first time when the sun was over the yard-arm, and who thinks that liking Tchaikovsky is a moral accomplishment —Amis does not need any enemies. Even so, Fussell’s remains a useful and insightful book about an indispensable man of letters.

An even better demonstration of Amis’s abilities has been undertaken by Sir Kingsley himself, in the form of his latest novel. Most of Amis’s novels are moral dramas cloaked in entertaining wit, satire, splenetic asides, and unfolding comedy. In that sense, they are traditional English novels evoking obvious comparisons. This latest one made me think of Jane Austen and Henry James. The drama or the melodrama is a test of perception, the story of what Richard Vaisey thinks, how he knows what he knows, and how his thinking is challenged and changed. Yet it is also the story of how on certain points of principle he refuses to change his mind.

The title, The Russian Girl, reminds us of earlier Amis titles, such as Take a Girl Like You; Girl, 20; and Difficulties with Girls. Why so many girls? The answer is that a girl can be an object of romance or of desire and, even more, a trial of epistemology and valorization, perhaps even a test of faith. This Russian girl, a poetaster named Anna Danilova, is a bit of a manipulator as well as a mysterious, possibly dangerous vagabond. Does one kind of fraud imply another? How do you know? The drama of the novel is how Vaisey makes up his mind.

He also has to decide a few things about his job, professing Russian in a brain-dead academy that has shot itself in the head, and about his wife, Cordelia, who is without doubt one of his most imposing Amisian creations since the unforgettable Margaret of Lucky Jim. Indeed, The Russian Girl seems to be a sort of middle-aged replay of that novel. In both, the protagonist is caught in the hell of the academy and twisted between two women. In both, he rejects the neurotic and escapes with the other. We cannot ignore the repeated comic resolution or blessing which implies that personal and even intellectual integrity can only be found outside university life.

The background of academic politics is not to be neglected—it is directly related to the ostensible personal crisis, reminding us of Jake’s Thing and Stanley and the Women. The betrayal of standards and the invasion of the academic world by hostile and incapable aliens are the grounds of Vaisey’s confrontation with The Russian Girl, forcing him even to reconsider his policy of rejecting bad poetry. Who but Kingsley Amis, who believes that bad poetry is not as good as good poetry and that we can tell the difference, would dramatize such a distinction? Of this novel as of Amis’s own poems, the reader can only say, as Fussell has indicated, “Thanks—I needed that.”

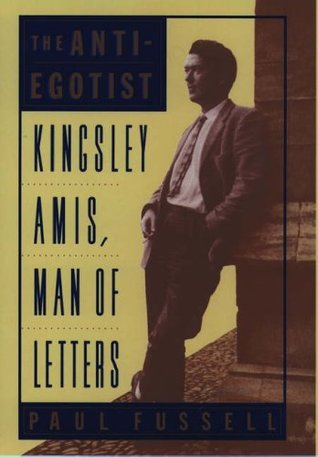

[The Anti-Egotist: Kingsley Amis, Man of Letters, by Paul Fussell (New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press) 224 pp., $23.00]

[The Russian Girl, by Kingsley Amis (New York: Viking Press) 296 pp., $22.95]

Leave a Reply