The stores are still vending the recordings of Vladimir Horowitz, the imposing pianist whose career is now as lucrative as it was during his lifetime. Nearly all of his work is out on compact disc, from sources dating back to the 1920’s. Merit and celebrity coincide in this case, as they sometimes do—and when they do, we would like to understand why. That means it’s time to hit the books.

This second biography of Vladimir Horowitz (1903-1989) barely mentions the existence of the first one—Glenn Plaskin’s effort of a decade ago. And I suppose that is just as well, since Plaskin’s book kept regressing to the Kitty Kelley mode and the tone of an expose. Plaskin’s book was spoiled by what still seems to be unresolved anger and an exploitative agenda. Certainly, no one can make such criticisms of Schonberg’s study, which has a couple of advantages in addition to the obvious absence of malice.

One of these advantages is ten additional years of perspective. In that time, Horowitz kept appearing and recording and even returned to Russia in a move that rounded off his life and actually had something to do with global politics. Schonberg’s view of Horowitz is more comprehensive and more comprehending for that reason, and for others. Another advantage is the author’s lifetime of devotion to music and performance, and especially to the piano. Harold C. Schonberg has been leading his own “Romantic revival” since at least the 1950’s in his books and reviews, and in Horowitz he finds the personification of 19th-century virtuosity. Schonberg’s Horowitz is the book he was born to write. His themes of interpretative freedom and the singing line naturally find themselves exemplified in his subject. His love of great piano-playing finds its fulfillment in this treatment of just that subject. The puritanism, inflexible rhythm, and pseudo-historical consciousness that mar the performance of so much music today are all rebuked by the example of Horowitz.

And there is another advantage, I think. A biographer (like his subject) has to make up his mind about what Yeats called “perfection of the life or of the work.” Schonberg has made his choice: he focuses on Horowitz’s claim to fame and subordinates, though he does not scant, the personal elements. I think he is right to do so. Still, in describing the burden of musical prodigy and in showing the extent of Horowitz’s self-absorption, Schonberg has at least by implication reckoned the cost in personal misery of so much musical achievement. Horowitz himself tried to separate life and art in many ways—in his dandyism, his isolation, his neurasthenia, his inversion, and his neglect of others, as well as in his mastery, his self-imposed challenges, and even his triumphs of connection with the public he teased. He paid a price in his mental and physical health, in his place in musical history, and even in his music-making. To some degree, I think Horowitz should be called to account a bit more strictly than Schonberg does.

Schonberg does his best work in outlining the Romantic context of Horowitz’s background. He shows its strength in validating Horowitz’s individuality as such performers as Battistini, Rachmaninoff, Friedman, and Kreisler (and the musical culture they represented) passed away, leaving Horowitz very nearly “The Last Romantic,” as his publicists claimed. However, I also believe Schonberg lets a paradox escape him. Until 1961, Horowitz had always appeared in the West as a “modernizer”—the young savage of the late 20’s with the close-cropped hair. Then in America he was a Red Seal artist with Toscanini and Heifetz—streamlining, even reductionist vehicles of the repudiation of Romanticism. Was it “Romantic” to play like a machine? Horowitz was sometimes a voice of industrialism and a destroyer of nostalgia in the 1940’s and 1950’s. Schonberg lets this point go, for example, in considering the 1932 landmark recording of Liszt’s Sonata in B minor.

Then, too, he has changed his evaluations of certain recordings—what were once deemed as flawed in various ways are now subsumed in the glory of Horowitz’s best work. And I think Schonberg is just plain wrong about Horowitz’s interlocking octaves at the end of Chopin’s Scherzo in B minor. The point is not that his effect can be justified, but that the unison scales Chopin wrote are harder to bring off: Horowitz’s “effect” is an evasion of difficulty that can hardly be classified as “virtuosity”—”inappropriate cheap stunt” would be more like it, though a stunt at the highest level, to be sure.

Furthermore, since music is such a vital part of culture, the testimony of Horowitz’s few pupils shows not how much but how little he connected with them. Horowitz performed, but he didn’t do much to pass on what he knew, as other great pianists such as Schnabel, Cortot, and Serkin did pedagogically and in print. Horowitz’s narcissism was a crippling limitation.

But never mind—the man was a hero of the keyboard. Schonberg’s is a stirring and convincing book, and he is right that Horowitz was the greatest pianist of the second half of the 20th century. He is right that Horowitz had a demonic quality that actually scared people. He is right that Horowitz had an uncanny ability to control sound, to weave textures, and to fill the biggest hall with unique sonorities. And he has a point in calling for a reassessment of even Horowitz’s Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert.

Schonberg’s Horowitz transcends its subject, even as Horowitz’s recorded performances are more than individual statements. The recreative freedom, lyric-dramatic projection, and sustained line of Horowitz’s best work remind us of how much we have lost in disconnecting ourselves from the past. And that gap, a fissure running back to the outburst of modernism and the First World War, has swallowed up more than our musical heritage.

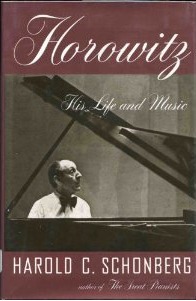

[Horowitz: His Life and Music, by Harold C. Schonberg (New York: Simon & Schuster) 428 pp., $27.50]

Leave a Reply