Think of all the ink spilled on foreign policy during the 80’s. Yet for all of Clinton’s “accomplishments” on foreign policy (Middle East “peace,” NAFTA, Haiti), the subject did not even appear on the political radar screen during the 1994 elections. Frankly, voters do not care, and no fact of American political life brings a neoconservative to tears more quickly.

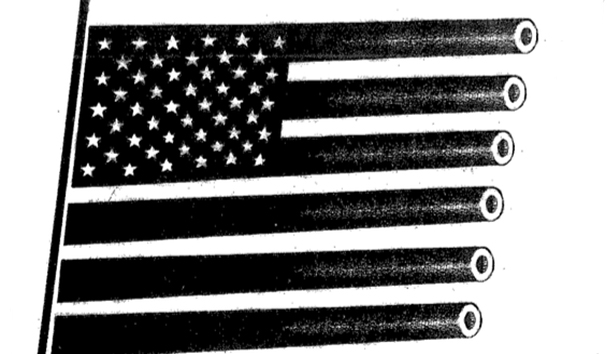

To understand the neoconservatives, we need to be aware of their implacable pursuit of American empire. Their military program requires keeping massive numbers of troops, ships, planes, spies, and bombs stationed around the world, ready for use at a moment’s notice, as well as keeping the public hopped up to fight any foreign country labeled an enemy. It was the New Left’s skeptical view of this program that led the neocons to defect to the official right, which—thanks to the Cold War—was far more hospitable to empire.

The relationship between the official right and the neocons was cozy during the late 1970’s and 80’s, and over time, these formerly distinguishable movements became largely indistinguishable. Both, for example, were dedicated to Reaganism, which meant a bigger welfare-warfare state in the name of limited government.

For the social democrats, the end of the Cold War was a terrible moment. It meant they could no longer paint every skeptic of the military machine as a “Blame America Firster.” They would have to deal with sensible critics, especially on die Old Right, who favored a more traditional defense policy. This put strains on their relations with the entire right, and on their ability to peddle a messianic foreign policy to the American public.

The neocons know, as we all do, that American public sentiment is basically isolationist. That is to say, we care more about our own country, region, state, and community than about the plight, real or alleged, of foreign peoples. The perceived threat of Soviet communism overrode this isolationist impulse, but there is nothing on the horizon—not even Kim Jong II—that can replace it, or call forth the same level of public deference to Washington.

With the end of the Cold War, the neoconservatives split into two camps: universalist and neonationalist. The universalists argued that American foreign policy should have one principle: the promotion of social democracy through military power everywhere on the globe. Among this camp’s prominent spokesmen were Greg Fossedal, Ben Wattenberg, and Josh Muravchik. For them, no place on earth should be allowed to escape the blessings of neocon rule, as imposed by the State Department, the CIA, and the Army. What if other countries did not want American-installed social democracy? That is an illegitimate question, and an illegitimate thought. To the universalist neoeonservatives, only cultural xenophobes would argue that not everyone needs the welfare state, universal suffrage, an imperial executive, civil rights, and fixed elections every four years. Just as the universalists expect Americans to give up their cultural identity, so do they want foreign peoples everywhere to sacrifice the same, as they are merged into the universal nation.

The neonationalist neoconservatives—represented by such figures as Irving Kristol, Jeane Kirkpatrick, and Charles Krauthammer—agreed in principle with most of the universalists’ position. But they introduced a caveat. Yes, every country can and should have social democracy, but there are times when it is not in the American “National Interest” to send off the armed social workers. They even named their foreign policy journal the National Interest.

This view has nothing to do with the Monroe Doctrine that many on the Old Right found persuasive. That doctrine warned Europe to keep out of this hemisphere, and promised that we in turn would keep out of Europe. The neonationalists make no geographic distinctions. Indeed, Krauthammer has warned that the dread notion of “spheres of influence” is making a comeback, thanks to Clinton’s defense of an invasion of Haiti on the grounds that it is in our “backyard.”

To the neonationalists, having an undemocratic regime in our hemisphere is no more or less compelling a reason to intervene than if it were overseas. What then is the “”? This is to be determined by the foreign policy elites under the neocons’ wings and on the basis of a wide number of considerations that cannot be enumerated in advance of a declared emergency, such as a threat to the permanent sex party in the palace at Kuwait.

On one level, this internal neocon debate seems superficial. Both camps, after all, want a massive military, a giant foreign aid budget, a controlled crew of foreign policy experts, an imperial presidency, and a Congress that is too cowardly to exercise its constitutional war powers. Both sides favored the Gulf War, pleaded for intervention in Bosnia, cheered the bombing of the alleged plotters of George Bush’s death, wanted to annihilate North Korea, and salivated over a second war on Iraq. And both sides want a gushing foreign aid spigot and massive spy agencies.

But they do not agree on all wars. The neonationalists split with the universalists on Somalia, Rwanda, and Haiti, fearing that intervention in such places would discredit militarism itself. But even the universalists should have cringed over the foray into Haiti. Here is a country where voodoo reigns, where the masses are illiterate and violent, where there is nothing resembling the rule of law, and where it makes no difference to American security whether Haiti is ruled by Aristide the voodoo priest or one of his zombies. As civilized people, we wish the people of Haiti well. As citizens and taxpayers, we say: your troubles are your own.

Our Old Right forebears felt the same in December 1914, when, as Charles Class recounts in the Spectator, “The U.S. Marines were dispatched to Haiti to confiscate $500,000 in gold from the Haitian treasury and deposit it with the National City Bank of New York.” After the full-scale Marine invasion of July 1915, the “National City Bank was awarded ownership of the treasury and forced Haiti to borrow $40 million at high interest.” American forces then took control of the customs houses to insure that the loan was repaid. President Wilson noting that “control of the customs houses . . . constitutes the essence of this whole affair.”

The Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Franklin D. Roosevelt, crowed to the New York Times in 1920: “The facts are that I wrote Haiti’s [1918] constitution myself, and if I do say it, I think it is a pretty good constitution.” Why? For one thing, it changed the basic law of 1804—which had forbidden foreigners from owning any part of Haiti—so American corporations could confiscate 266,000 acres of the best agricultural land under American military protection. President Eisenhower also sent the Marines to Haiti, to insure that the “pro-Western” Papa Doe Duvalier would stay in power. “Pro-Western” meant, then as now, wholly owned by the State Department.

Today, the best thing we could do for Haiti is to trade with its business classes. Instead, the United States imposed crushing sanctions, driving an already impoverished people into ruin. Clinton then promised to shoot the country into submission. Only Jimmy Carter’s hard work and Christian decency prevented this, as they prevented another Korean war.

The Wall Street Journal editorial page, the voice of neonationalist neoconservatism, panned the idea of an invasion for weeks. As for the universalist neoconservatives, they were strangely silent. Here was their theory being tried out, and they were nowhere to be seen. Here was Fossedalism, Muravchikism, and Wattenbergism in action. Like the Journal‘s editors, they may have feared that an invasion would discredit American foreign policy. So they left it to the New York Times to defend the Haitian adventure, which looked more and more like a criminal enterprise every day our troops were there.

American troops paraded all over the country, busting down the doors of private homes and businesses, confiscating privately owned guns, and then inviting mobs to loot and destroy what was left. The Pentagon kept telling us it had to disarm and jail the members of FRAPH, the attaches, the gunmen, the thugs, etc. They had to shut down radio stations and the press. They had to gag and arrest anybody who had a gun or who opposed the United States government. Sounds like what Clinton would like to do in America.

“In a worrisome incident the U.S. military still hasn’t disclosed,” reported the journal, “the 25-man Haitian army garrison in the isolated mountain town of Belladere rebelled Thursday night. Following a confrontation between U.S. Army forces there and the Haitian commander, the Haitian troops locked themselves in barracks. After the U.S. forces demanded they come out and blew the locks off their doors, one soldier ran out of the building . . . and was [killed]. There were no U.S. casualties.” The Haitian troops “rebelled“! So we dragged them out of hiding in their own country? And murdered a man? Somebody explain to me why this is not terrorism.

In the first speech by the communist cokehead Aristide after his installation as president by the United States, he urged the mob to grab people they thought were gunmen, or attachés, or FRAPH members, or whatever, and thereby unleashed a torrent of looting. That was only the beginning. Yet we kept hearing that the Haitian mission was a success. For whom? The United States got away with an immoral war; the mobs in Haiti got a pound of light-skinned flesh; and Haiti got a voodoo-socialist government, courtesy of the American tax-payers. And that courtesy has only just begun, because the foreign aid Haiti receives will quickly reach a half-billion dollars, and go up from there.

The isolationists on the paleoconservative right condemned the Haitian outrage from the beginning. Like Albert Jay Nock, they know that “Every State, from the earliest to the most modern, is a robber-State. Of its instruments for effecting robbery, the most primitive, and now most costly, are armies and navies. These are used chiefly in safeguarding the economic exploitation of weak alien peoples by the State’s beneficiaries at home.”

It will take years to sort out the corrupt network of interrelated interests that made this Haitian operation possible. We know the Meys family of Port-au-Prince and Miami was involved, along with its Washington hired gun, a former roommate of Clinton’s. We know that each member of the congressional Black Caucus was paid off to give the invasion the proper racial cover. We know that Mena, Arkansas, is no longer a major drug transshipment point, and that Port-au-Prince now is. Beyond that, we will have to leave it to the revisionist historians.

But what of the neonationalists? Once the American troops hit the ground in Haiti, they fell silent. Not a peep was heard from the Journal‘s editorial page for two weeks, although plenty was said about Saddam Hussein moving a few pathetic soldiers around his own country as a protest against sanctions still starving women and children years after the tank-bulldozers finished burying Iraqi troops alive in the desert.

Iraq’s movement of its pitiable “elite Republican guard” offended the Czechess Madeleine Albright, somehow our ambassador at the United Nations, and the Ukrainian John Shalikashvili, somehow chairman of the joint chiefs, so the editors at the journal started flashing their little pocket knives. Of course, neocons of every stripe were relieved when Clinton proved himself willing to go to war on behalf of an arbitrary line in the desert sand drawn by British imperialists. Monday of the next week rolled around, and the other shoe dropped. At the top of the journal editorial page was a flattering pencil sketch of “Father” Aristide, minus his thousand-mile stare. There was “widespread skepticism about Mr. Clinton’s adventure,” the journal wrote, “which we ourselves expressed before the troops started to move. Yet we find it hard to root against the success of U.S. arms. . . . The people of Haiti have known nothing but repression, it’s true, [so] giving them a chance at a piece of the modern world can only be a good thing. . . . We would also reserve the hope that when some future President intervenes for reasons that include Realpolitik, [there will be no] scoffing about world policemen.”

A “piece of the modern world”? What is that, the chance to go on welfare so long as you obey the central state? Is the world not “modern” enough as it is? In fact, the journal has the future wars it wants fought, and so decided that it cannot oppose other military adventures for fear that it might help Americans think for themselves, and therefore endanger the entire empire.

There is a lesson here. At the domestic level, consistent and principled opposition to the central state and all its domestic works is the most moral and effective stance we can take for reviving our rights and liberties. It is no different on foreign policy. We must be consistent isolationists, and oppose every military adventure—a priori—of this or any other administration. There is no need to palaver over whether an intervention is or is not in our National Interest. War sustains the Leviathan, and so is against the American people’s interest. So is every Roosevelt dime of foreign aid, every CIA killer-spook, and every international managed-trade racket like NAFTA and GATT.

In this effort, the Republican agenda is worthless, since it docs not confront the state’s war-making power. This means we must also oppose Newt Gingrich’s call for vast increases in military spending. Republicans, however, were not always worthless. Warren G. Harding, the best President of this century, promised: “If I am elected, I will not empower any assistant secretary of the navy to draft a constitution for helpless neighbors and jam it down their throats at the point of bayonets borne by United States Marines.”

This is our tradition. Let the social democrats call us isolationists. It is a name wc should bear proudly, for it represents the only moral foreign policy.

Leave a Reply