Was wollen die Frauen? Freud’s questions are always better than his answers, and even his questions usually betray the diseased mind which poisoned this century with its sexual obsessions. In a healthier age, the question of what women wanted would not have been asked, but as we look out across the wreckage of human social life—the singles’ ads in the newspapers, the sex videos advertised so prominently in the New York Times book section, the sex hardware hawked in Harper’s, the strange phenomenon of middle-class women preferring shackups to marriage and going out of their way to bear bastards, the bone-tired mothers who reluctantly put their children in daycare in order to spend eight hours a day in a job they do not particularly like and come home to cook and clean for a husband who will not lift a finger to help them—Freud’s question echoes in our ears like the sound of wild dogs barking in a ghost town.

Our friend Professor Kopff has been after us to bestow an annual Was Wollen die Frauen award on the woman with the least excusable husband. In the past few years since he first made the suggestion, we have had our choice of any number of women in the public eye. Hillary Rodham might head a Democrat’s list. Even conceding that she is exactly what Newt Gingrich’s mother said she was, Mrs. Clinton was not born with her mouth turned down in a dyspeptic scowl. Imagine what it is like to be a bright, ambitious woman trying to turn something like Bill Clinton into presidential material in the odd moments she can distract him from chasing girls or striking poses in the mirror. If the dead can be included, then Nicole Brown Simpson deserves an honorable mention, and if we do not insist too much upon the sex of the spouse, so does Lisa Marie Presley.

Perhaps the strangest cases are the women who run off with other women. I used to know a high school Spanish teacher who lost his job for showing erotic foreign films to his students. The last time I ran into him he was trying to negotiate a deal to film the life of Sirhan Sirhan. When I began making fun of the idea, the bartender said, “Leave him alone: his wife just ran off with the Avon lady.” Decades before Thelma and Louise, I had been hearing of professors’ wives who ran off with each other. What wives, what husbands.

Why do women marry the men they do? In some cases it seems to be the same maternal instinct that impels some women to become nurses. They are so many Honoria Glossops eager to take care of that army of Bertie Woosters who constitute the male sex. In graduate school I knew a lovely and intelligent girl who ended up marrying the ugliest male I have ever known. Looks are not everything, of course, and this guy was surly, arrogant, lazy, cowardly. For a while the young lady was being courted by a friend of mine, who, although not a man I might want for my daughter, was, at least, unambiguously Homo sapiens sapiens and, I have to admit it, rather charming. My friend knew that the young lady was a potential Florence Nightingale, eager to console the sick at heart, and he confessed to her all his failures, weaknesses, and self-doubts. He was neck-and-neck with his rival until Gargantua announced that his father had died. My friend resigned the field, declaring one night in the graduate seminar room, “I can’t top that.”

I am not sure I know what it means when so many women marry men they want to take care of. In a general way, the eligibility of bachelors is a sign of social esteem. In a warrior society, strength and courage are the qualities that women look for in a husband; in a plutocracy, it is wealth; and in the most degenerate ages of the world girls go mad for gladiators or film stars with greasy hair and steroid-inflated pectorals. Of course, in more sober times it does not matter too much what women may think they want, because the standards of eligibility are set, not by Hollywood PR men, but by the fathers who want their daughters to produce successful grandchildren.

In higher civilizations, which are universally patriarchal, the girls and boys may have little say in the matter. Why should they? If my genetic future is in the hands of my grandchildren, then I cannot allow the character of my posterity to be determined by a teenager’s whim. Marriage is not a sexual romp in a motel room; it is real life, full of disappointments, pain, sickness, failure, and death. Good looks, divorced from other more solid qualities, are mere sex appeal, the quality of film stars and other prostitutes. The sort of husband or wife that parents want for their children would be good-looking, of course, because good looks are an indication of health and an omen of success. But there are other important qualities: the ideal spouse would himself be healthy and come from a healthy stock; he should be as intelligent as his social position demands but no more, since intelligence, when unrewarded, turns to envy and mischief. A potential husband should display courage, self-restraint, but why go on reciting the list of virtues that Aristotle catalogued in the Nicomachean Ethics? The obvious point is that since young people cannot possibly make a well-informed marital choice, their parents or guardians should have some say in the matter, if only the power to veto their children’s decisions.

In our civilization, before it was Christianized, marriage was a contract between families, not between individuals. Greek sons had some say in selecting their brides, and even daughters knew how to manipulate daddy—as the young Nausicaa does in the Odyssey. Roman law was more severe: no unemancipated child could marry or divorce without the father’s permission. But even in Rome it was up to the father to enforce his rights. Cicero gritted his teeth and allowed his daughter to choose a (third) husband he did not particularly like.

When Romans began converting to the Christian faith, they did not jettison, all at once, either the ceremonies or rules of marriage. Early Christian weddings were solemnized with the same pagan ceremonies we use today—the vows, the rings, and many of our customs are Roman—and eventually priests were invited in to bless (but not marry) the couple. The important change was Christ’s insistence upon marriage as an indissoluble union. Although the concept of the married couple as united in flesh was known both to pagans (e.g., Lucretius) and Jews, it required Christ to repudiate divorce and St. Paul to explain the deeper meaning of marriage. Since Christians conceived of marriage as a mystical union, they could not, in principle, compel their children to marry. On the other hand, the Christian understanding of the duties of parents and children did not include the right to contract a marriage against parental wishes, although the Church did, eventually, step in to validate elopements.

It was not until the Reformation that secular princes began to assume the power to regulate marriage, and since that time parents have gradually abandoned their pretensions to select or even veto the children’s selection. It is easy to blame Christianity or the Reformation for the secularization of marriage and the decay of parental responsibility, but the moral and political problems of modern marriage do not admit of facile analysis or glib solutions.

Trollope’s novel Lady Anna presents the spectacle of a mother and daughter in conflict over a marriage. The mother had married a wicked Earl, who subsequently repudiated the validity of the marriage and the legitimacy of his daughter. After his death, the Countess and her daughter live on the charity of a radical tailor and his son as they attempt to prosecute their claim to the late Earl’s personal estate. A young and honorable cousin, who has succeeded to the title, naturally contests their claim until his lawyer, the Solicitor- General, becomes convinced of the justice of the ladies’ claims and proposes a marriage scheme as a tidy arrangement for uniting the title with the money. The new Earl is handsome and noble, the Countess’s daughter lovely and charming. The Countess, embittered by her sufferings, now begins to hope for a happy issue of all her afflictions, when the daughter, Lady Anna, discloses that she is betrothed to the tailor’s son. To a Romantic sensibility, this might be a tale of true love thwarted by ambition and class snobbery, but Trollope takes the case to an aging radical romantic—obviously Wordsworth—who explains to the young man that class distinctions have a purpose. Comparing the old nobility to hothouse plants and the tailor to a “blade of corn out of the open field,” the poet concedes that neither species is “higher in God’s sight than the other, or better, or of a nobler use.” However, they are different, “and though the differences may verge together without evil when the limits are near, I do not believe in graftings so violent as this.”

The poet’s first response, when he has heard the tailor’s account of the affair, goes to the heart of the matter: “When you spoke to the girl of love, should you not have spoken to the mother also?” But conscious of the mother’s social ambition, he concealed the betrothal, and Lady Anna, though tempted by the beauty of the Earl’s person and by the pleasant dignity of his life, is as tough and persistent as her mother. Her mother’s happiness, the fortunes of the family she has learned to admire—all depend upon her decision, but she is true to the radical tailor.

A lesser novelist might have painted the Earl and his family as degenerate aristocrats or given the Countess a more appealing character, but Trollope sees the situation as a conflict not between good and evil but between different kinds of good. When a friend tells her, in a muddled way, that it is her Christian duty to live in the state to which God Almighty has called her, “the nobly born young lady did not in heart deny the truth of the lesson;—but she had learned another lesson, and did not know how to make the two compatible. That other lesson taught her to believe that she ought to be true to her word;—that she especially ought to be true to one what had ever been specially true to her.”

It is only the Solicitor-General—like Trollope a conservative liberal—who sees both sides of the case, arguing first against the folly of letting the girl throw herself away on the tailor and later against excessive severity, once it is clear she has made up her mind. The Countess is, undoubtedly, a harsh mother whose obstinate pride has made matters worse, but the snake in this garden is not a mother’s pride but a young man’s stubborn individualism and contempt for social distinctions. His neglect of parental rights is a sign of his deeper desire to overturn society. One can only hope, for the girl’s sake, that he has not adopted the Jacobin view of marriage as a temporary convenience.

The marriage ceremony devised by the Jacobins was something less solemn than “Gentlemen, start your engines,” and the Hebertiste procurator of Paris designed a pretty little divorce ceremony in which he congratulated the couple on their decision to start a new life. The pendulum has swung back and forth several times in 200 years, but the leftward forth is always further than the rightward back. By the 1970’s, it was being argued that marriage is fundamentally incompatible with modern life. However, the leftists who used to make the case for open marriage, “swinging,” group sex, child molesting, and incest, soon discovered that even if ordinary people do not honor marriage in fact, they cling to the superstitions of monogamy even as they are concealing their affairs or explaining a divorce to their children.

The superstition of marriage is more than sentimentality. What distinguishes us from our admirable first cousins, the gorillas and chimpanzees, is the human race’s preference for a stable household and a statistical tendency toward monogamy. George Gilder’s notion (borrowed from Lionel Tiger) that women, in forcing men to quit their jackrabbit ways and settle down to a k-strategy of propagation, created civilization, is pure bosh. To the extent we are men we are family men, and the species might better have been named Homo familias.

Of course, the survival of our race depends not on good judgment but on appetites. In primitive circumstances it is difficult to get enough protein and fat in the diet, hence modern man’s excessive consumption of steak, and if sex were not the other greatest pleasure, our species would have died out a long time ago. By way of insurance man has a greater sex drive than he needs, and the more virile and ambitious he is, the greater his appetite for women, hence Edward O. Wilson’s description of man as slightly polygenous. True civilization, so far from being inconsistent with human nature, is man’s fulfillment. If primitive men protect their body with skins and extend the use of their hands with chipping tools and throwing sticks, civilized men wear togas or three-piece suits; they design crossbows, chisels, and split bamboo flyrods. In this sense, culture is hypertrophic in exaggerating our natural tendencies. If sex roles are only sketchily defined among hunter-gatherers, great civilizations are all patriarchal and do everything they can to emphasize and celebrate the differences between the sexes.

The problem comes when civilizations succeed in producing a leisure class with excess wealth. Under these conditions, men start acting as if they had read Lionel Tiger. No longer content with a fling or two, successful men begin to find ways of getting around marriage. They consort with prostitutes and take concubines, but that is not enough. We are all, so far as we are human, marrying men, and if we cannot get what we want in the arms of one wife, we can always look for another and another and another until we exhaust our resources—and our energies. In the late days of the republic, the Roman upper class went through a marriage crisis that we do not find remarkable today, simply because it seems to mirror our own.

Divorce revolutions typically strike the very rich, because only the rich can afford to waste their time on amours. There is no evidence to suggest that the Roman elite’s immoralism spread to the other classes, even to the provincial squirearchy that was the backbone of the empire. But the great genius of democratic capitalism is that it brings upper-class degeneracy within the reach of every man, woman, and child. The role of democracy is fairly straightforward, since modern democracies refuse to tolerate distinctions of any kind—of class, sex, region, religion, race. The political engine of democracy is always envy and resentment against anyone who happens to possess a peculiar advantage that cannot be justified by a universal rule. If rich women can afford to pay a doctor to kill their unborn babies, then poor women should be given the same opportunity to kill theirs. If Nelson Rockefeller can die embracing two prostitutes, why cannot I, at least, have access to the Playboy Channel?

The role of capitalism is somewhat more complicated. (I am not criticizing the free market, or even big business, but a political-economic system in which the great economic interests are able to buy governments and use them both to further their own interests and to invade the private and social spheres of everyday life.) Marx and Engels recognized the symptoms: ‘They have dissolved every bond between man and man and replaced it with the cash nexus.” Capitalism is a powerful energy; it thrives on growth and must expand or die. That, in a nutshell, is the philosophy of the Wall Street Journal. The most benign form of expansion is imperialism. Japan had to be chivied open by my wife’s ancestor to create markets for American business, and in the 1950’s Dwight Eisenhower declared that American business interests dictated an expanding military role in Southeast Asia.

Those business interests ended up costing American taxpayers a sum of money that is a substantial part of our national debt, and they levied a blood tribute on the young men of my own generation, just as they had levied even greater tributes upon my father’s and grandfather’s generations. Robert McNamara probably regards the Vietnam War, which spelled the collapse of the American political system, as a small price to pay for affluence. The really serious victims of democratic capitalism are internal, for as much energy as goes into international expansion, there is enough left over to devour all the moral habits and social institutions that are the capital reserves inherited from a precapitalist world.

Capitalism has to make money, and if capitalists cannot sell refrigerators to Eskimos, they have to find ways of turning noneconomic activities into commercial transactions. Once upon a time our ancestors knew how to entertain themselves: they told stories, played musical instruments, and read, over and over, the few books they owned or could borrow. Boys played rude games, and when they grew up they hunted and fished with gear they might have inherited. Not much profit in any of that, but with a little social restructuring we were persuaded that it was better to listen to phonograph records than to play the piano, to watch the Super Bowl than to play softball. The publishing industry could hardly get rich putting out a few good books a year or republishing the classics; a whole market of bestsellers had to be created—fast literature to be consumed along with fast food. Even hunting and fishing have been almost completely commercialized. The sign you see in tackle shops says it all: “He who dies with the most toys wins.”

Well, even I am not immune to the thrill of a well-made rod or the allure of a new rifle. The earliest men worked hard on their spears, and the division of labor and specialized craftsmanship arc only additional examples of cultural hypertrophy, but capitalism was not content with commercializing our recreations. A great sphere of human life lies outside the market: the household, within which relationships are defined by love and friendship rather than by price or cost. Capitalism’s greatest triumph was learning how to buy and sell love.

On the surface, the idea seems preposterous. A family is not a random set of individuals brought together for some common purpose. The persons in a family are members, limbs of an organism; they are bone of each other’s bone, flesh of each other’s flesh. Modern Christians stick at the mystery of the Trinity, but the relationship of parents and children is precisely that of different persons with one substance. The law of the marketplace is competition, but the family’s law is love, and even if my wife be neither beautiful nor pleasant, she is my wife, and my children, though they be stupid and lazy, remain mine forever. One cannot properly buy and sell within the family, any more than one can engage in commercial transactions with one’s self.

As a consequence, the family and the household are impregnable bastions of precapitalist society against a capitalist world. Such is or was the ideal down to the Victorian era; in practice, the family has been capitalized and commercialized. To get its fingers into the organic unity of the household, democratic capitalism had to find the seams and cracks; it used the principle of equality as a crowbar to pry wives away from husbands, children from parents—it was called liberating individuals from the tyranny of patriarchy; and it learned how to divide and subdivide the family into economic functions of production and consumption, which were increasingly brokered out to external providers. Food, which was once grown, preserved, and cooked within the family, is now at best reheated; children are turned over to daycare, kindergartens, schools, and counselors; entertainment now means the consumption of commercially prepared experiences and even the ordinary pleasures of games and conversation is turned over to the Little League, the YMCA, and “after-school activities.”

But capitalism’s greatest triumph has been its successful attempt to replace the Christian concept of marriage as a mystical union of male and female into one flesh with a model based on the limited partnership. Marriage, we are told, fulfills certain needs and functions—sex, companionship, childrearing—and the durability of a marriage depends on the degree of success it has in carrying out the functions. Another species might construct a workable arrangement on this utilitarian basis, but mankind was not so created. Within a marriage we cannot split off erotic desire from companionship or parenthood without doing violence to all three marital qualities. Indeed, it is something of a strain for young men to form innocent friendships with women, because there is always, lurking in the background, another possibility. This is what harmless flirting was all about in the old days, a formalized method of mock-courting designed to prevent things from getting out of hand.

In dividing sex from marriage, capitalism has created a commodity that can be bought and sold. Of course most developed societies sell women’s favors, but the very existence of prostitution serves to define what marriage is and is not. Burke observed, during the American Revolution, that slaveowners have the keenest sense of liberty; similarly, the matron is ver}- much aware that her social status is the very opposite of the prostitute.

In singling out sex as an attribute of marriage (and of male-female relations generally) capitalism blurs the distinction between married love and sex-for-sale. Tomorrow, for example, is Valentine’s Day, once upon a time a quasi-Christian holiday honoring tender and honorable affection, but now a celebration of lust. NBC will parade the Sports Illustrated swimsuit models; husbands are told to buy their wives red teddies from Frederick’s of Hollywood; and the local newspapers are running features on romantic getaways for couples—cozy lodges with Jacuzzis, vibrating beds, and mirrored ceilings. With any luck, Valentine’s Day will turn into an erotic Christmas, marketing everything from a kiss on the cheek to bestialist peep shows, because whatever can be turned into money is the equivalent of everything else that can be turned into money, and the moral result is the perverse banality that “finds a wealth in division, / Some kinds of love are mistaken for vision. La te ta ta ta.”

In late-capitalist America, women are marketed like meat—graded on scales of one to ten, advertised with glossy photographs, videos, and computerized sex bulletin boards, where it is possible for the geekiest Kuwaiti undergraduate to claim his First Amendment right to simulate the rape and murder of a fellow student. Even decent girls are aware that most men, by the time they reach twenty, have poisoned their imaginations on hundreds of hours of explicit pornography, and in nice suburban schools, girls are groped and fondled as they walk through the halls. They are taught, before they reach puberty, that when they go out on a date, they are expected to show their appreciation. Not so long ago fast girls kissed on the first date; today, they are expected to display a detailed and practical knowledge of the Kama Sutra (more multicultural richness).

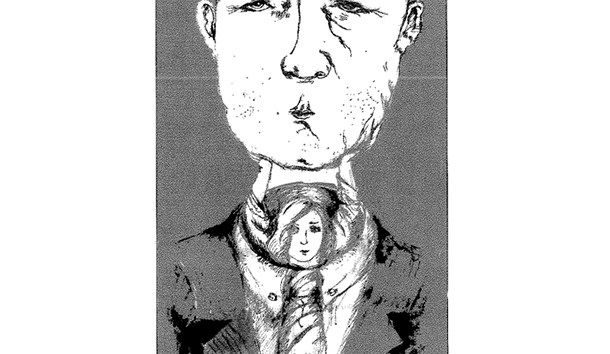

It has been some time since young men came to the door and spoke politely to the parents. Today a complete stranger to the family drives up, the stereo booming, and honks the horn, and somebody’s daughter disappears into the darkness. Even in better times girls go astray, no matter how strict their fathers. Today, even if girls have a father in the home, he will try hard not to be judgmental. He remembers what he did when he was young, and while an earlier generation of rakes, knowing themselves, used to send their daughters to convent schools, few men are willing to accept the responsibilities of fatherhood. It took only two generations and two world wars for the degeneracy of the Edwardian upper class to devour the bourgeois proprieties of Edward’s mother and to reduce the status of all women to the level of prostitutes and prey. To win elections, we gave them the right to vote; to enhance profits and lower wages, we sent them out to work; to ensure a steady flow of sex without commitment, we staged the sexual revolution; we abandoned all the responsibilities of manhood and took to reading fashion magazines and talking about our feelings; and then we wonder why some women have learned to prefer other women, and we have the nerve to ask what women want. What in the name of Hell do men want?

Leave a Reply