Overwhelming force is war’s only mercy

Alan J. Levine must be praised for his courage in discussing the United States’ atomic bombings of Japan without the tears, whining, and pleas for international forgiveness that are now requisite. The “confusion” discussed by the author was, of course, present in 1945, but it is now a largely artificial, post-1945 construct of the republic’s internal enemies—those in the media, the universities, the Democratic Party, and Hollywood.

Because of these critics, the use of the atomic bomb falls into another contrived category of America’s imagined “great sins”—such as slavery, misogyny, and white supremacy—for which penance, self-humiliation, and reparations are owed forever. This ersatz confusion can be cleared away by applying common sense.

The quality of America’s leading military minds slowly decayed after 1945. U.S. generals forgot the basics of the American way of war established during the Civil War. Both Union and Confederate generals displayed great common sense in recognizing that it would be long and bloody. Facing this fact, they operated on the belief that war’s only mercy is a speedy conclusion producing irrefutable victory, attainable only by using overwhelming force to exert maximum human and material destruction upon the foe.

Since 1945, however, U.S. generals, whenever directed to fight, have learned to deploy the mantra of bureaucrats and politicians that “there is no military solution.”

Through a quarter-century of Indian Wars and then the Great War, U.S. generals strove to deliver war’s only mercy. But World War II imposed a new and evil era of coalition warfare and binding alliances on America. Suddenly war was not only to be declared and funded by Congress, but the fighting of wars would now require a significant role for celebrity-seeking domestic and Allied politicians, diplomats, pundits, and other prominent, non-military outsiders.

Levine’s able discussion of the differing viewpoints behind the decision to strike Japan with atomic weapons shows the corrosive impact of four years of coalition warfare and the U.S. government’s policy of war-by-committee, which often included fewer uniforms than business suits. As Levine shows, the diplomats—former Ambassador to Japan Joseph Grew, for example—insisted it was Washington’s responsibility to clarify unconditional surrender to encourage a Japanese surrender. The diplomats also argued that the U.S. government must take actions—or at least use words—to strengthen the hand of the “Japanese peace faction” in trying to end the war. This, perhaps, started the eternal U.S. search for “moderates” in governments that are, in fact, sworn enemies. During the war, other bureaucrats, experts, and professors also opposed attacks on the material symbols of Japan’s culture, those tied to the emperor, for instance.

Levine notes that by the war’s end, almost no senior officer resolutely opposed using the atomic bomb. President Truman, to his credit, authorized the atomic attacks. The opponents of this strategy acquiesced, and the war ended. But Levine’s apt depiction of the pre-Hiroshima “confusion,” should not have been found among men involved in the decision-making. All of them were capable of reflecting on the clear lessons they had learned by living through the 1935-1945 period of high international tensions, depraved human behavior, and world war.

First, Roosevelt’s embargoes on Japan deliberately forced Japan’s leaders to choose between economic disaster, military decline, and dishonor, on the one hand, and a probably suicidal war, on the other. The Japanese chose the latter, ready to win or die in the endeavor, and so gave Roosevelt the Pacific war he—or those around him—wanted. In risking national extinction, Japan made the use of the atomic bomb a simple necessity and an easy decision.

Second, from Pearl Harbor to the Battle of Okinawa—which was still raging as the bomb’s use was debated—Japan’s army and navy fought to the death to defend the emperor, the empire’s possessions, and their honor. Therefore, no U.S. civil or military leader had a reason to think Japan could be persuaded to surrender before suffering a definitive military defeat. Indeed, ferocious Japanese resistance to U.S. Marines on every invaded island increased markedly as Admiral Chester Nimitz’s command advanced toward Japan’s home islands. The only common sense conclusion was that invading Japan would make Iwo Jima and Okinawa look like cakewalks.

Third, U.S. leaders had also just watched the staggering violence of the German-Soviet War, one in which Stalin and Hitler willingly expended as many of their countrymen’s lives—military and civilian alike—as were necessary for victory. Surely common sense dictated that the U.S. must avoid a ground war in the rugged land the Japanese held sacred.

Military planners exhausted all options short of invading Japan. Given the utter unlikelihood of an unforced Japanese surrender, and the equally unlikely success of Admirals King and Leahy’s view that “blockade and conventional bombing could end the war without invasion,” the atomic bomb was the best available alternative.

However, Levine’s claim that such an invasion “was a terrible idea which should never even have been considered” must be discussed. There was no viable option to invasion in early 1945, and on the eve of Hiroshima’s bombing, no senior American leader could be absolutely sure the atomic bomb would detonate. It would have been, it seems, extremely negligent not to have prepared for a post-Okinawa invasion of Japan. If the atomic bomb failed and no invasion plan was ready to implement, the war—given Japan’s code of honor, devotion to Hirohito, abundant ground forces, armed civilians trained to hate and fear Americans, and enormous stockpiles of military and civilian supplies—would have gone on and on.

The bomb did work in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, however, and Japan—with help from its god-emperor and a failed Army officers’ coup—surrendered soon afterwards. The attacks cost not a single American life, and saved countless more by making an invasion unnecessary. The bomb was, if you will, the definitive America First weapon.

Regrettably, atomic bombs were not available for delivery on April 18, 1942, when Lt. Col. James Doolittle and his squadron of B-25 bombers flew off the USS Hornet to bomb Tokyo and other locations on Honshu island.

I will add one last reason for neither questioning nor feeling remorse for the atomic bombing of Japan. My father was a U.S. Marine, serving in the 5th Marine Division. The 5th Marines—along with the 2nd and 3rd Marine Divisions—were selected for Operation Olympic, the planned invasion of Japan’s major and southernmost home island, Kyushu. My dad survived the Marines’ hard work on Iwo Jima, but the odds would have been against him and many tens of thousands of others, had the invasion been necessary.

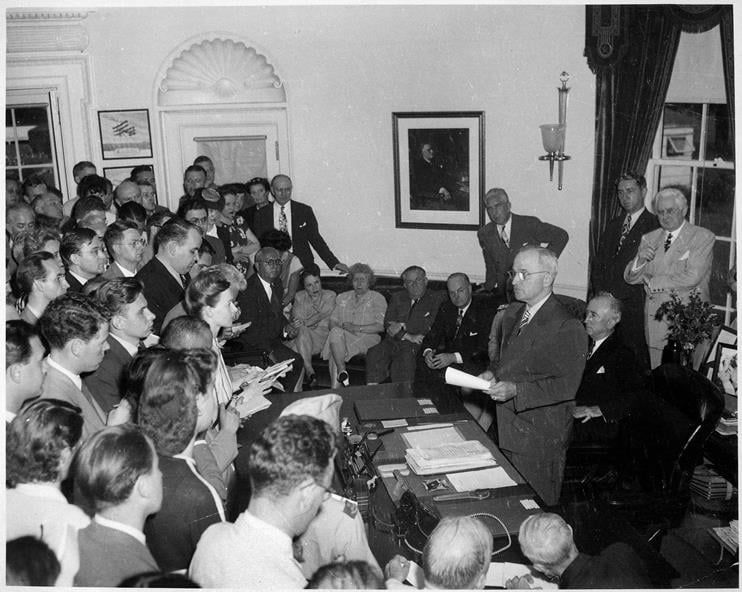

Image Credit:

above: President Harry S. Truman in the Oval Office reading the announcement of Japan’s surrender to assembled reporters and officials on Aug. 14, 1945 (photo by Abbie Rowe/National Archives and Records Administration/Harry S. Truman Library)

Leave a Reply