When I mention that I am reading Robinson Jeffers, even cultivated and well-read people look bemused; the name seems obscure. By way of explanation, I borrow the closing words of the classic gangster film The Roaring Twenties: “He used to be a big shot.” Just how big Jeffers had once been is hard to convey today, and so is the depth of his collapse in reputation.

But the case for rediscovering Jeffers is overwhelming. On so many points, he speaks to strictly contemporary concerns and obsessions: about American identity, torn by endemic conflict between republican values and the imperial/military dynamic; about urbanism and corruption; about localism and regionalism, and a patriotism rooted in landscape; about the natural world or “the environment,” and deep time. And he held to his core values faithfully against the growing hostility of the larger culture. Had he been more prepared to shift those views, to tack to the prevailing winds, he would not have vanished as thoroughly as he has from popular consciousness.

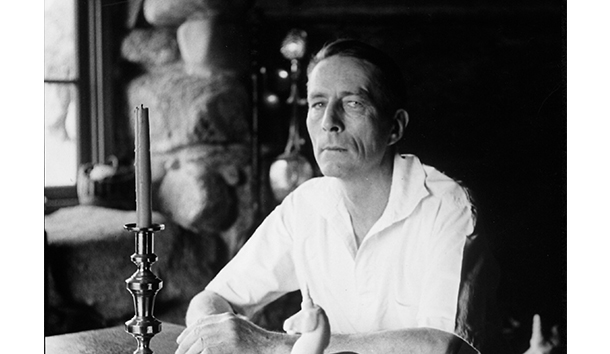

Born in 1887, Jeffers first earned national celebrity with collections such as Roan Stallion, Tamar, and Other Poems (1925). He scored more triumphs through the 1940’s, and remained vigorously productive until his death in 1962. For much of the mid 20th century, Jeffers enjoyed a stunning reputation. When Edward Abbey quoted Jeffers, he would not bother to name him but instead just called him “The Poet,” and literate people knew whom he meant. Jeffers was the favorite poet of Charles Bukowski, and Gary Snyder and Ansel Adams were devotees. In the 1930’s, Jeffers and T.S. Eliot were commonly ranked side by side as the great living American poets. In 1932, “the Whitman of Big Sur” was on the cover of Time.

Jeffers was a versatile author, whose finest achievements were in drama as well as poetry, and in other styles that resist standard generic classification. Besides many memorable shorter pieces, he turned out some very long verse narratives or epics, including Tamar, Cawdor, The Loving Shepherdess, and Give Your Heart to the Hawks. (To take just one example, the last of these runs to almost 30,000 words.) In effect, these are substantial novels in verse form, which can stand alongside any of the best American fiction of the era. In particular, Jeffers does a brilliant job of psychological observation, of explicating obsessions, of studying souls in extremis. His dialogue is at least as strong as that of any of his better-known prose contemporaries. Only the fact that they were written in verse prevents these epics from being a much more secure part of the literary canon today.

Each of the major works is deeply imbued with ideas from mythology, drawing on Jeffers’ total immersion in Classical literature and drama, augmented by a heavy dose of modern anthropology. These writings contain a potent Gothic sensibility (to say the least), and the mysticism is pervasive. The Californian settings are gorgeous and memorable. Indeed, even if we set aside the other virtues, his ability to convey a sense of place in itself justifies reading him.

Besides the obvious Classical exemplars, his writings demonstrate a profound familiarity with the Bible, and especially with the Old Testament. That is scarcely surprising as Jeffers was so heavily influenced by his father, a Presbyterian professor of Old Testament Literature and Biblical History at Western Theological Seminary, in Pittsburgh (now merged into Pittsburgh Theological Seminary). We can trace far more Calvinism in Jeffers’ worldview than he might have cared to admit, and more of a prophetic quality in his concept of the poet’s role. He aspired to be Ezekiel as well as Aeschylus.

In theme, if not in style, Jeffers often echoes his younger near-contemporaries, William Faulkner and Eugene O’Neill—for better or worse. In fact, the three together would make a wonderful subject for a joint critical biography. Commonly, Jeffers will describe a family rent by some crisis, which culminates in an act of atrocious violence, such as a murder or blinding. Tamar, for instance, which became wildly popular, portrays a family living in California’s Point Lobos, headed by David Cauldwell, with his children Lee and Tamar. The family lives under multiple curses, including an original sin in the form of incest, which is re-enacted by the new generation of children. Tamar becomes increasingly disturbed, and domestic hostilities culminate in murder and arson.

As in the greatest Greek tragedy, these verse novels deal with grim subject matter, even to the point of inviting parody, but they are far from lugubrious. Part of their appeal is their combination of the epic and Euripidean with the strictly contemporary American detail, finely observed. In Give Your Heart to the Hawks (published in 1933), the tragic plot is simply described. Fayne Fraser is married to a Californian rancher, Lance, who suspects her of infidelity with his own brother, Michael. Lance kills his brother in a drunken rage, a crime that Fayne covers up successfully. Driven mad with guilt, Lance commits suicide. The story recalls both the ancient Greek Furies, and the tale of Cain and Abel. Yet for all its cosmic resonances, everything is firmly rooted in a very 1920’s rural California, a world of gas stations, trucks, and diners, of beach parties where the characters have drunk too much illicit gin and are amenable to skinny dipping. And when he wanted to be, Jeffers was shockingly good at depicting low life. One partygoer has brought along a pair of louche waitresses on the razzle, one of whom—horrible to relate—strips to reveal extensive tattoos. We could so easily be in a John Steinbeck novel, or a Thomas Hart Benton painting.

Their literary style makes even the longest poems surprisingly accessible. Although Jeffers clearly fits alongside so many other Modernists in most ways, he rejected what he considered the stylistic affectations of much contemporary verse, with its abstruseness and intentional difficulty. He dismissed these devices as Gongorism, in a reference to the ornate and often pretentious writings of Spanish Baroque master Luis de Góngora. Jeffers, in contrast, wrote with beautiful lucidity.

By 1940, Jeffers’ career was flourishing magnificently, and the question naturally arises: What can have gone so badly wrong? The answer lies in politics, and Jeffers’ stubborn adherence to the idea of an Old Republic, which was threatened by the rise of Empire. His political commitments became increasingly contentious, to a degree that would gravely harm his reputation.

Already in 1925, his “Shine, Perishing Republic” was a deeply pessimistic jeremiad against an America on the verge of rapid and inescapable decline, overcome by corruption, urbanism, and the ills of mass society:

While this America settles in the mould of its vulgarity, heavily thickening to empire,

And protest, only a bubble in the molten mass, pops and sighs out, and the mass hardens . . .

Note the “this America”: There would be others, and probably soon. The more rapidly the United States metastasized into an empire, the faster her fall would be. In the meantime, signs of coarseness and brutality abounded, and threatened honest citizens: “We shall beware of wild dogs in Europe, and of the police in armed imperial America.” And did this failing civilization dare to project its values, its flawed modernity, into a wider world? Such a missionary impulse was “So eager, like an old drunken whore, pathetically eager to impose the seduction of her fled charms / On all that through ignorance or isolation might have escaped them” (“The Coast-Road”).

“This America”—the political order symbolized by Constitution and republic—was distressingly fragile and temporary, as was evident to anyone familiar with the eternal verities of the American landscape. In 1930, his “New Mexican Mountain” portrayed tourists from the soulless cities, who are in search of a spirituality and beauty that is quite unavailable to them in their regular lives. Accordingly, these “pilgrims from the vacuum” have traveled to watch a tribal ritual performed by impoverished Pueblo Indians in quest of tourist dollars. Amid the general air of near despair and mutual contempt,

. . . Apparently only myself and the strong

Tribal drum, and the rock-head of Taos mountain, remember that

civilization is a transient sickness.

The republic stood in such deep and imminent peril, as did civilization itself. In this vision, another global war would mark a terminal catastrophe, driving the country to extended empire, over-ambition, and eventual decay. In the 1930’s, Jeffers was inevitably anti-interventionist, anti-imperialist, and radically isolationist, views that were powerfully reinforced by having two growing sons who would soon be of military age. Loathing Hitler as a warmonger, he resisted countless calls to enlist in communist or popular-front causes, as he condemned the totalitarianism of both left and right. For Jeffers, the appropriate American response should be: a plague on both your houses.

He saw the interventionist foreign policy of Franklin Roosevelt’s administration as a blatant attempt to deceive the nation into another destructive war, along the lines of 1917. We can argue at length about the various conspiracy theories on FDR’s role in provoking U.S. entry into war, theories that generally focus on the President’s supposed foreknowledge of the Pearl Harbor attack. I personally have no sympathy for such conspiratorial claims about that particular event. But at the same time, it is beyond argument that the administration was indeed working hard through 1941 to provoke a naval war in the North Atlantic, with a view to finding an excuse for an open declaration of war on Germany. When Pearl Harbor happened, the only surprise was that the new war had broken out in the wrong ocean.

Jeffers was furious, disgusted, and contemptuous, and he poured forth his wrath in the poem “Pearl Harbor”:

Here are the fireworks. The men who conspired and labored

To embroil this republic in the wreck of Europe

have got their bargain,—

And a bushel more. . . .

The war that we have carefully for years provoked

Catches us unprepared, amazed and indignant.

For Jeffers, what was so appalling was not just the cynicism of the efforts to provoke war, but the stark incompetence of the administration when confronted with the result they had sought. They were like wayward children trying to detonate an illicit firework show, and treating the whole bloody enterprise as a mischievous jape. And these reckless buffoons wanted to impose an American Peace on the whole world!

Jeffers followed “Pearl Harbor” with many shorter pieces that developed the same themes. In 1943, his “Historical Choice” declared that

—we were misguided

by fraud and fear, by our public fools, and a loved leader’s ambition

To meddle in the fever-dreams of decaying Europe.

He counted FDR among the “pimps of death.”

To say the least, Jeffers was a very long way from the patriotic consensus that followed Pearl Harbor, and the fact that he was arguably right about the “conspired” and “provoked” offered him no protection. These and other lines gravely damaged his reputation, to the point of making him radioactive. When “Pearl Harbor” and other poems were collected in The Double Axe (1948), the appalled publisher added an extremely unusual disclaimer: “Random House feels compelled to go on record with its disagreement over some of the political views pronounced by the poet in this volume.” If the author had been anyone less prestigious than Jeffers, now a Grand Old Poet, they would have much preferred to refuse publication.

The affair shows how far the U.S. political spectrum had shifted since December 1941. Before Pearl Harbor, isolationist and America First views were thoroughly respectable, and even mainstream: The America First Committee was an authentic grassroots mass movement, the youthful supporters of which included both John F. Kennedy and Gerald Ford. By 1948, in contrast, Jeffers’ poems made him sound like a fascist diehard, which he assuredly was not. And all this at a time when FDR had achieved a kind of secular sanctity, so that Jeffers seemed to be spouting blasphemy. In his distant fastness at Carmel, he looked less like a prophetic Western visionary than a ranting foe of democracy and modernity, a Californian counterpart to Ezra Pound.

The Double Axe affair certainly did not end his career, and his dramatic works enjoyed spectacular global success, especially his Medea. But if other poets and authors continued to adore him, his stock in the public market fell catastrophically. For decades, he was not taught in academe, and only recently has he regained some popularity as a pioneering Modernist. That, in short, is how one of the truly great American writers dropped off the cultural map.

I began by quoting an iconic American film, so let me end in the same vein. In Sunset Boulevard (1950), a faded silent-movie actress angrily rejects the suggestion that she used to belong to the big time. “I am big,” she says: “It’s the pictures that got small.” We might say something similar about Robinson Jeffers, who asserted big values and ideas in a diminished culture, a shrunken public square. It was not that the grand causes that he championed had lost their relevance or shriveled in significance in his final years—far from it. Ideally, those issues should have been central to cultural debate in the decades following his death, in the turmoil of the 1960’s, and in the forward march of the military-imperial state. It was not that Jeffers had slipped from the big time, but rather that the culture had become too small-minded to hear his words, too limited to comprehend their Classical and Biblical underpinnings.

In terms of its politics no less than its cultural assumptions, Jeffers’ work should strike an immediate chord with readers of this magazine. If Chronicles ever decided to nominate a (secular) patron saint, I have a fine candidate—one who used to be a big shot, and who properly should be again.

Leave a Reply