The Godless Constitution is a self-described polemic against those who believe that the United States was, is, or should be a “Christian nation.” Essentially a historical analysis of the religious influences on the Kramers of the Constitution, the book explores the superficially curious omission of God, even the simplest and most formal invocation, from that document. Religion is mentioned in the text of the Constitution only negatively, in the celebrated prohibition against demanding religious tests for officeholders. The authors conclude that this sparse treatment reflected a deep conviction about the proper place of religion within the new society: by no means a hostility to God, but a determination to institute a rigid separation of church and state. The Constitution is indeed godless, and by design.

It is a sad commentary on the present cultural climate that such a historically obvious argument should appear so controversial, and even partisan. In the last two decades, a whole literary subculture has emerged with the intent of demonstrating the “Christian nation” hypothesis, and its works proliferate in evangelical bookstores across the country. Commonly, these books offer a catena of quotations from the Founding Fathers, noting that on given occasions various leaders spoke of God or Christianity, and assuming that these terms were used in a sense not too far removed from contemporary evangelical Protestantism. At its most extreme, this literature proceeds to Christian Reconstructionist conclusions, arguing that the United States should fulfill its “Christian” mission by implementing the stern decrees of Old Testament criminal law. However, even moderate religious conservatives share the assumption that the United States was somehow hijacked by secularists at some moment in its history, in an act that betrayed an original mission or covenant. Leading the nation “back to God” is the agenda that underlies controversies over issues like school prayer, gay rights, and abortion.

For Kramnick and Moore, this widely held belief is a myth, and contributes to a general attitude that they term “religious correctness.” Unlike many moral debates, this issue is reconcilable once and for all by scholarship, and the authors have performed the service with devastating effect. They trace the opposition to church establishment through American history, focusing on such figures as Roger Williams, Thomas Jefferson, and the 18th-century Baptists, and describe the constitutional debates over whether a formal nod might be made to the deity in the new frame of government. In this context, they make the point that in 1787, only two of the state constitutions lacked formal recognition of the Christian religion, but these two were Virginia and New York, the homes of Madison, Jefferson, and Hamilton. It was chiefly under their influence that the federal government was born godless, and the other states followed this lead in the following decades. The “Christian America” debate is brought to the present through a history of recurrent controversies over such topics as the appropriateness of Sunday mail delivery and the passage of an explicitly Christian amendment to the Constitution. Whether or not one accepts the basic argument of the authors, the book offers a rich mine of thought provoking information that should be valuable for any future disputes about the religious and moral underpinnings of this society.

In view of current controversies, perhaps the oddest factor about the secularism of the Constitution is the degree to which it grew from Christian roots, and especially that radical sectarian Protestantism which found its noblest and most cantankerous representatives in the Baptist church. The authors have the great virtue of lifting the veil of retrospective mythology that has surrounded many leading figures in American history. Of Roger Williams, for example, they note that his rigid opposition to the religious establishment had nothing in common with a soggy indifferentism, but rather was a logical extrapolation of Calvinism. Government was a creation not of God but of depraved humanity, and for Williams, “Government existed because God did not rule the world.”

The Godless Constitution is strong on the European, particularly the English, background to the separationist idea, and correctly places the foundation of the United States in a particular historical era when “orthodox” religion was at an absolute low point in terms of its appeal among social and political elites. We can only speculate how much more explicitly Christian or evangelical would have been a document produced, say, in 1850. In reality, the country “was born at a moment in Western history when emancipatory fervor sought to free individuals from the restraint of both the medieval Christian commonwealth and the medieval mercantilist economy.” I would probably go even further than they do in considering the distinct religious environment of the 1770’s and 1780’s, the decades when liberal and anti-Papal Catholicism reached its apogee in Latin and German nations.

In the Protestant context, the previous century had witnessed a precipitous decline in belief in those aspects of Christian theology which were deemed “mysterious” (a stinging epithet in those years) or which contradicted God-given Reason. This category of obnoxious doctrine expanded steadily from the idea of Hell to such fundamental notions as the Trinity, the Divinity of Christ, the Incarnation, and the Resurrection, all of which were increasingly blamed on the machinations of “priestcraft.” This was a powerful condemnation for English or American Protestants, accustomed to a ferociously anti-Catholic and anticlerical political tradition. In 1772, for example, a large group of British Anglican clergymen petitioned Parliament to be excused from subscribing to the traditional creeds or articles of faith, on the grounds that orthodoxy for a Protestant should only mean agreement with Scripture as one interpreted it. When supporters were criticized as “sectaries,” one Member of Parliament reacted furiously: “Sectaries, Sir! Had it not been for sectaries, this cause had been tried at Rome. I thank God it is tried here.” That conjunction of orthodox doctrine with “priestcraft,” clericalism, and Papal tyranny was powerfully in the minds of the American leaders, and goes far toward explaining the extreme nervousness about God entering the Constitution, through however narrow a gate. It was specifically to clerical power that Jefferson was referring in his famous declaration of “eternal hostility to every form of tyranny over the mind of man.” How appropriate that one of the greatest of the monuments in the nation’s capital should be inscribed with such a starkly anticlerical tirade.

Without such “monkish” and medieval doctrines as the Trinity and the Incarnation, Christianity was an ideal religion for reasonable and enlightened men and women: part of Nature, “as old as the creation,” it manifested that same Divine Wisdom that guided all good individuals through history, both before and after the time of the man Jesus, and as present in Persia or China as in London or Philadelphia. There was no Original Sin, and if there were a single unforgivable violation of divine law, it was sectarian intolerance or persecution. This Christianity, based on service to “Nature’s God,” was expressed as well in the fellowship of freemasonry as in any church, and it is surprising that the present book does not make more reference to the influence of Masonic thought. In the American context, the Founding generation was thoroughly acquainted with these distinctive concepts of God and the Christian religion, and it was in this sense that they were so prolific with their references to America’s divine plan: a Christianity so rationalist that it would have earned excommunication or death for any adherent in Pilgrim Massachusetts, just as it would cause the dismissal of a professor in a modern Southern Baptist seminary.

In summary, Kramnick and Moore show the importance of sound historical scholarship for contemporary social thought, and their conclusions are unassailable. Future generations might, if they chose, repeal any or all of the clauses barring the establishment of a national religion, but they would be deluding themselves if they believed they were returning to the original intent of the Founding generation.

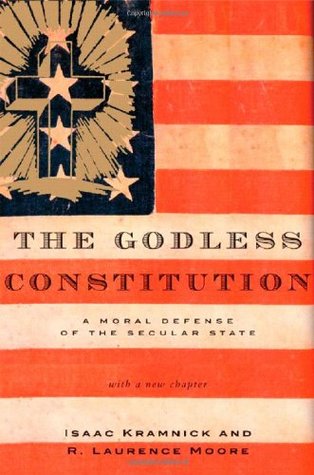

[The Godless Constitution: The Case Against Religious Correctness, by Isaac Kramnick and R. Laurence Moore (New York: W.W. Norton) 191pp.,$22.00]

Leave a Reply