The 1997 movie Wilde opens with a shot of Oscar Wilde (played by Stephen Fry) being lowered by bucket into a Colorado silver mine, where he recites his poetry and chats with shirtless, sweaty miners, who are obviously thrilled at a visit from such a renowned visitor. I thought it was at least half Hollywood fantasy until I came across the same anecdote in The Unmasking of Oscar Wilde by Joseph Pearce, who writes, “At Leadville in Colorado he was lowered in a bucket into a silver mine” where “he spent most of the night deep in the heart of the earth, talking to the miners, before being brought down the mountain by a special train at half past four in the morning.”

If nothing else, the episode illustrates, intentionally or not, the importance of literature in society in the days before television, when everyone hungered for it, regardless of class or background. After its promising opening, unfortunately, the movie degenerates more or less into one sexual romp after another, with no real examination of Wilde’s literary importance. And even the opening foreshadows what is to come, with Wilde casting an occasional keen glance at the young, wiry miners. That the movie takes this tack comes as no surprise, since it is based on Richard Ellmann’s salacious Oscar Wilde, considered by many to be the standard biography.

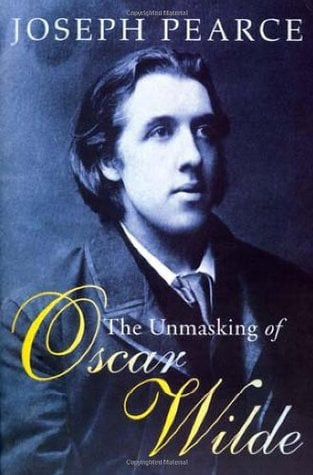

The Unmasking of Oscar Wilde makes no such mistakes. Indeed, one of Pearce’s objectives is to debunk the conclusions of many of Wilde’s biographers, especially Ellmann, even while relying heavily on Ellmann for anecdotes and other material. “Over the years, [Wilde] has been served by a string of biographers who have betrayed him with either a kiss or a curse,” Pearce writes. Zeroing in on Ellmann, he adds, “the enshrining of Ellmann’s study as the ‘definitive biography’ was in need of serious reappraisal. As a life of Wilde, it is fairly comprehensive in facts while it remains largely uncomprehending in truth.”

Another objective is to rescue Wilde from those two rotten factions, the puritans and the prurient. The former rejects Wilde because of his immoral life; the latter celebrates him for the same reason. Both sides, blinded by their bias, probably miss the irony.

According to Pearce, in order to understand Oscar Wilde, you have to examine his work and leave on the periphery his public image, which was made up of whatever “masks” he chose to wear. Wilde actively cultivated an image of himself as an aesthete, the most visible aficionado of the late-19th-century decadent movement that thumbed its nose at Victorian mores. To the public, even to his wife and closest friends, Wilde presented such masks as his dandyism, his decadence, and his keen wit. In his writing, however, the masks come off, revealing a man tormented by temptation and consumed by the possibility of redemption, even in his darkest moments. “Repeatedly,” Pearce writes, “Wilde reenacts Calvary in his works, most of which are Passion plays in various poses, depicting the wounding of love by the wicked . . . an expression of the conflict between Wilde’s worldly mask and his inner self.”

Now, concentrating on Wilde’s work may sound obvious, but most modern literary biographers do not work that way. Many make a writer’s work peripheral, while trolling his public image for whatever lurid details they can find. Or they rely on Freudianism, making assumptions for which they have no evidence, based on facts they do not understand. Thus, for example, J.R.R. Tolkien’s official biographer, Humphrey Carpenter, chalks up Tolkien’s fervent Catholic faith to his feelings for his dead mother. The possibility that Tolkien believed in Catholicism because it is true does not seem to register. So it is with much of the material on Wilde, and two culprits are Ellmann and another biographer, Melissa Knox, who, makes no bones about her Freudian leanings referring to her book, Oscar Wilde: A Long and Lovely Suicide as a “psychoanalytic biography.”

Pearce does a fine job discrediting these writers in his analysis of Wilde’s flirtation with, and rejection of, the Catholic Church as a young man. Battling internal conflict and “sickened by his own weakness, [Wilde] is filled with anxiety and remorse” for not converting, Pearce writes. Ellmann and Knox, however, ascribe (despite sketchy evidence) Wilde’s self-loathing to having contracted syphilis while at Oxford. Ellmann even says that Wilde died of it, despite the overwhelming evidence that he died of meningitis.

Knox, on the other hand, while begrudgingly accepting that Wilde “probably” did not die of syphilis, still “insists that he probably had it anyway.” She offers no evidence for this other than her need for Wilde to have had syphilis for her hypothesis to work: “It is not so important that Wilde had contracted this disease as that he appears to have believed he had,” Pearce quotes Knox. “He behaves as though he were living under the shadow of the horror, the uncertainty, the guilt of the feeling that he had committed a crime against himself by contracting the disease and of having bestowed it again and again with a kiss.” The result of such sloppy reasoning is devastating—“the last refuge of a scandal monger,” Pearce writes, and he justly condemns it:

In reality, the impact of the invention of Wilde’s syphilis by his biographers is hard to overestimate. As Ellmann claims, his conviction that Wilde had the disease “is central to my conception of Wilde’s character and my interpretation of many things in his later life.” But if Wilde did not have the disease, where does that leave Ellmann’s book?

These are the sort of conclusions one would expect from people for whom scientific determinism has replaced sin and the psychiatrist’s couch, the confessional. Wilde, for all his faults, suffered from no such delusions. Citing the “guilt-laden recriminations” found in much of Wilde’s writing, Pearce says they “have their origin elsewhere than in the syphilitic. It is likely, in fact, that they are rooted in nothing more, or less, than a healthy conscience, accompanied by a consciousness of the objective nature of sin.”

Still, there were contradictions that became ever more pronounced as Wilde’s public image gained respectability. By 1886, he was married, a father, and, of all things, editor of a woman’s magazine. At this time, he started a series of sexual flings with young men, the first only 17 years old. Other liaisons would follow, culminating in the disastrous affair with Lord Alfred Douglas, the youngest son of the Marquess of Queensberry (he of the famous boxing rules), whom Wilde met in 1891.

The story of Wilde’s exposure and ruin at the hands of Queensberry is recounted by Pearce in riveting fashion: the bombastic Queensberry publicly calling Wilde a sodomite; Wilde responding by suing Queensberry for libel; Queensberry countering by entering a Plea of Justification; and finally, a jury returning a verdict in Queensberry’s favor, saying, Pearce recounts, “that Queensberry had been justified in calling Wilde a sodomite in the public interest. Queensberry’s triumph is Wilde’s downfall.”

It was a complete downfall, with Wilde sentenced to two years of hard labor; it was not a permanent one, however, for it led, despite many falls, to Wilde becoming a Catholic on his deathbed. Grace, it seems, reached Wilde through his suffering. It was in prison that he wrote De Profundis, which Pearce calls “one of his most important works in literature.” Here, the masks finally drop: “Nowhere in its pages is there the barest hint of the disingenuous,” Pearce writes. “He had forsaken all masks to brandish the inadequate, naked truth of his soul.”

Pearce is the right person to have written this book. There are many similarities between him and Wilde, not least of which is that both are converts. Pearce himself has come “out of the depths,” overcoming an upbringing as a “Protestant agnostic” (his words) and a youth spent as a white supremacist and a member of England’s National Front, for which he served two prison terms. It was during his incarceration that Pearce, like Wilde, experienced the first awakening of the faith that would lead him eventually to the Catholic Church. Perhaps he had discovered, like Wilde, “that every new approach to life leads infallibly to the same old truths.” Fortunately for the world, Pearce’s was not a deathbed conversion. He is still young, and I hope that many years remain in which we can appreciate his intellect and wit in biographies such as this one.

[The Unmasking of Oscar Wilde, by Joseph Pearce (San Francisco: Ignatius Press) 411 pp., $19.95]

Leave a Reply